Interview / KENU / Version 6

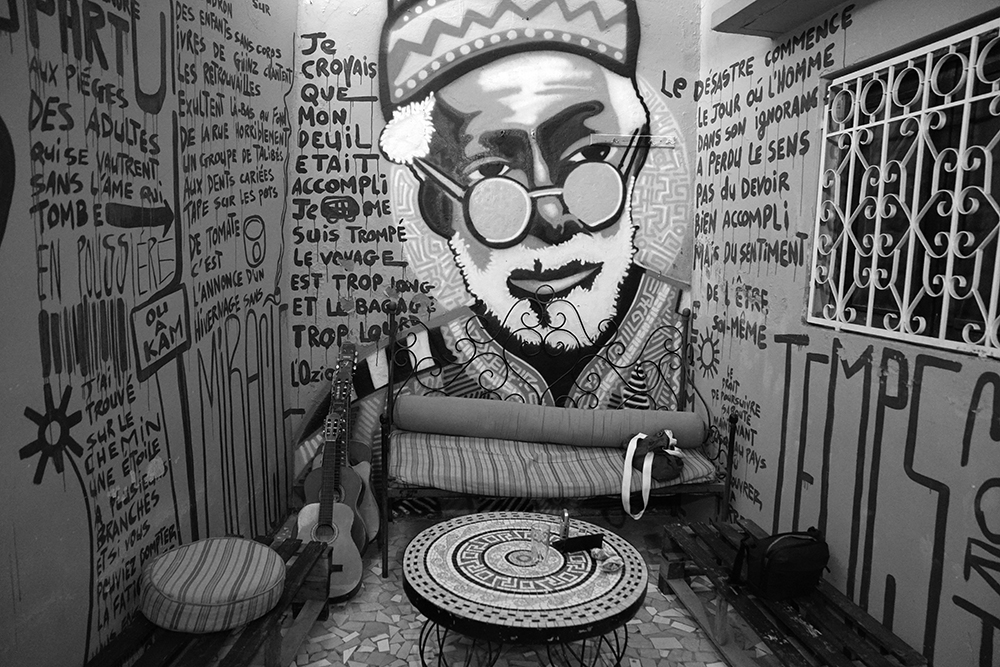

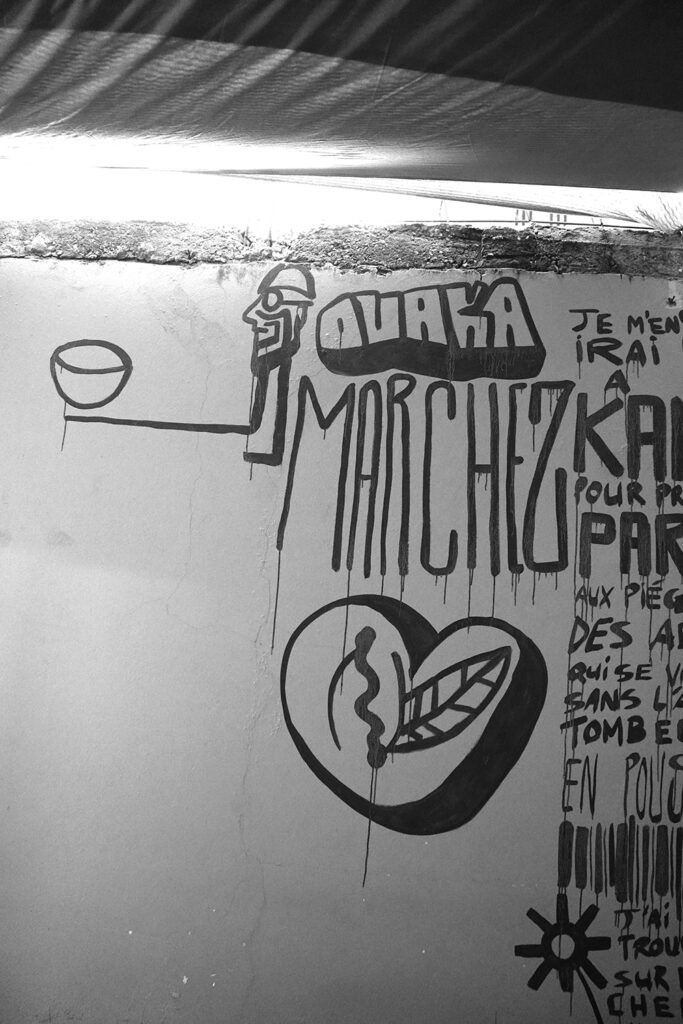

KENU – the LAB‘Oratoire des Imaginaires is a cultural space in Ouakam, Dakar, founded in early 2020 on the initiative of artist Alibeta Sarr. The collective sees itself as a resource center for activities related to education, mediation, production/distribution, and research. KENU is deeply rooted in diverse arts, African cultures, and its languages, with the mission of exploring the imaginaries, social practices, and traditional knowledge of Ouakam’s society. Inspired by action research methods, the LAB‘Oratoire utilizes tools from social sciences, popular education, and the arts to experiment with new ways of collaboration, to develop new forms of collective action in service of the community, and to reveal and expand the contemporary potential of traditional imaginary worlds.

Version: We are currently at KENU, your cultural center in Ouakam, where you are rehearsing your performance for Partcours 2022.

Alibeta: There will be a solar and tree installation by Jah Gal Doulsy. The idea was to examine African cosmologies, reflect on renewable energies, and explore how we can connect them with our mythologies and beliefs. When you look at African mythology, you always find the concept of the tree of life. At the same time, the installation will be a space for gathering, sitting, and discussing. We have written a fairy tale that we will perform there. Right now, we are rehearsing the songs, and there will also be a program with discussions.

Ibaaku: Talks and also screenings of films that have the same theme, namely environmental issues. These are films that we created here at KENU with different members. We held workshops where children learned to film with mobile phones. We also encouraged them to explore Ouakam and identify what interests them, what they want to talk about here, and which topics matter to them.

Version: You told us how important it is for you to connect the people of Ouakam with this center and integrate them into what you do.

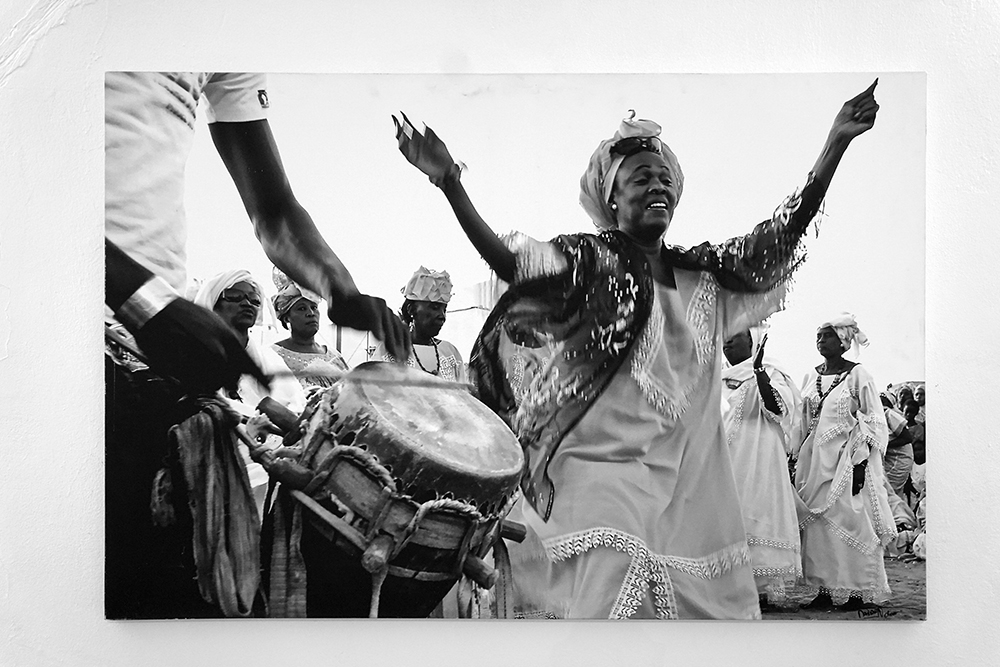

Alibeta: At the beginning, we lived in this house, but as musicians, we traveled a lot, performing across Africa and Europe. But we asked ourselves how we could involve our own community. If they don’t have access to what we do, what is the point of what we do? We have criticized this whole art system, this network of the establishment in the art scene, from the galleries to the key figures. It’s always the same people, the elites, who have access. So, we asked ourselves: when we look at our communities and our history, what is the function of art? Its function is highly social and spiritual in everyday life. Culture is everywhere in every village. There is no specific place where you could say this is the museum for art or this is the place for a concept. So, we wanted to return to this relationality—the connection between art and life, how art and culture can be part of everyday life, and how we can discuss social issues. That’s why we started by analyzing our environment to understand it. From our findings, we developed artistic events, such as theater performances, and engaged the community. The idea was to make everything more democratic and rethink our relationship with culture and its various functions. Ouakam has a very village-like aspect. People have their own ways of connecting with culture and art, different kinds of ceremonies. They always hold ceremonies in the streets, always. So, one of the fundamental ideas behind this space is community life. We are part of the community, and we interact.

Version: That is a very different concept from what exists in Europe. There, art is often seen in a reactive way. Artworks are created for specific places that interact with different visitor groups. The genres are also relatively separate.

Ibaaku: With colonization, we adopted this practice from Europe as well, so we need to decolonize art. It’s about functionality. It’s always about why and how you use a particular medium or method. In southern Senegal, people still use drums to transmit messages from one place to another. These are sounds, but they serve a function. Masks have a meaning, a history—they are not just objects—, for example the Kankurang. In our linguistic world—Wolof—we have different words for music, which are tied to different contexts and used differently. In our tradition, there is no such thing as a museum space. A museum is where you see artifacts stolen from Africa and brought to Europe for display.

Version: But what do you think about returning stolen objects to museums here?

Alibeta: First of all, when you steal something, you have to return it. And whatever people do with what you return is not your concern—it is ours. If we talk about museums, they are part of our heritage. We cannot deny the existence of museums in Senegal. They are a colonial legacy. Maybe we need to rethink the museum. If objects are moved from a European museum to a place like the National Museum (in Dakar), it has an impact. Instead of going to the Louvre to see a mask, people would have to come to Senegal. But the idea isn’t just to bring the mask to a museum. Some objects need to be returned to communities to resume their spiritual functions. Even the language we are speaking right now is not ours. We are using it to communicate with you. We have inherited languages and museums. What we do with them over time is up to us. Restitution is the first step. We should not downplay this step. But how Africans will rethink the concept of museums is a task for the future.

Version: You use all kinds of media in your projects. What role do performance, sound, theater, movement, or dance play? Do you even use these categories?

Alibeta: If you take the word ‘ritual,’ it closely resembles the concept of performance. If you look at the rituals in the ethnic groups of the Diola in the south or the Serer, they function like performances. Performative art and rituals can be interconnected—it’s about space, attention to the object, and symbolism. That’s our work—renaming and re-appropriate things. But we also try to integrate colonial heritage because it is something we cannot erase. We need to incorporate it into something bigger, mix it, and transform it. It’s always about creating a connection to the legacies from different times. We have the heritage of Black African spirituality and culture. But we also have Christian, Islamic, and Arab legacies. The question is: how can we merge all these different heritages with our original one to create something new? I think that’s the world we are exploring.

Ibaaku: The irony is that most of these concepts are now called performance or art. The work we do aims to remind people here that these concepts are not foreign to them. In the field of electronic music, for example, there is widespread agreement on how sound can affect you and put you into different states, such as a transformative state or a trance. People here think electronic music, jazz, or rock, are something foreign. But it is not—it is something rooted in the local culture, like the idea that music or sound can convey a message or alter states of consciousness.

Alibeta: There is a battle of narratives in general. It is a battle of how Europeans portray themselves and how they depict their relationship with the world. For us, it is about how we tell our own stories. If you look at the relationship between Europe and Africa, there are thousands of stories that need to be rewritten. For a long time, it seemed as if the African art scene in Europe spoke on behalf of Africans. But it was Europeans who interpreted this art, so they were the ones speaking for African artists. We are in a time where we need to reclaim the narrative.

Behind the way Europeans perceive African art in general lies a certain narrative, but the way our own community perceives art requires different narratives. Narratives about resilience, self-determination, self-love, knowing one’s history, reclaiming one’s tools, revolution, and so on. How can we, especially from here, develop our own stories that replace the ones that have been told about us for centuries, until our own communities had this inferiority complex in their heads?

Version: The images we have of Africa are so deeply ingrained in our minds because they are still affirmed today. How do you think these images and narratives can be changed to open up new perspectives?

Alibeta: Every civilization, in its time, has proposed projects for society. Mesopotamia, Egypt—at every period, civilizations have risen and made proposals. In the last century, it was Europe. It rose with capitalism, technology, development, and so on. But now, it is in decline. The question is: What comes next? But we cannot always just criticize and react. I am tired of reacting. We always react to what Europe, the World Bank, or the International Monetary Fund say. We need to think about another concept for humanity—one that is fairer, more ecological, and centers people instead of money. And we believe that the next proposal of this kind can come from Africa because we have the necessary resources. Europe is the continent that has colonized the most countries across all continents. Now, Europeans need to listen and learn from others. The African continent has all these cultures and a vast body of knowledge—not just spiritual knowledge but also political knowledge. Just think of the Kouroukan Fouga, the Manden Charter of Mali. It existed before the Human Rights Charter. In Africa, in 20 to 30 years, the majority of young people will live, and Africa has immense natural resources. So, it is about developing new utopias and setting a new direction because we know that the old system is in decline. And there is a willingness among people to strive for another direction. Europeans come here with their bank accounts, their cars, and all their possessions, yet they are poor. Why? They are searching for meaning. I see so many of them here. They come here with the posture of saviors while, in reality, they are beggars. They are searching for a social project or a cultural project to give themselves the feeling of helping. They work in NGOs and come to „save“ Africa. But who is saving whom? This is an entire economic sector. Thousands of young people from this generation are involved in it. All across the continent, they are setting up projects. We also need to discuss what poverty means. What is true poverty?

Version: A lot of things are financed from outside—art, research, NGOs, and so on. How do you assess this type of external funding?

Alibeta: If you look at it today, Europe has exploited our land and resources for years, making a lot of money in the process. Now, they bring the same money back to us. To me, Europe is not offering help—it is just returning what belongs to us. It depends on how you see it. The question is how I can dissolve this relationship. We, for example, try to operate without subsidies because we want to be free. So, if someone comes with money, we can decide—we can choose. That is how we change the relationship. Because even if you bring money and we have the ideas, the concept, and the material, your funding cannot function without us. You need something from us as well.

Version: You mean that if we change perspectives, the relationships change as well? Would that be the precondition for being able to talk about some things on a different level?

Alibeta: It is time to change and reshape relationships. For example, all these institutions that provide funding know that it is problematic. They have been attacked by activists. So, they know that the way they run projects is not the right way. And simply changing the label is not enough—first slavery, then its abolition, then colonialism, and later development work—it is ultimately all the same. Here in Africa, we should not simply consume these concepts; we must actively participate in the discussion and proposals being debated on intellectual, philosophical, artistic, and political levels. It is a relationship, and everyone has a part to play. But first, Europeans must accept that they are wrong. That is the most important thing because you cannot exploit people for centuries and still offer advice and recommendations. It is about reparations and official acknowledgment of guilt—not just the return of objects. We cannot leave this solely to politicians. You, as citizens, must push for it and exert pressure; otherwise, everyone will just care about their little stability and security. We, as citizens of our countries here, also have a responsibility. If we put more pressure on politicians, they may understand that we no longer want this. African communities and the formerly colonized world have the responsibility to reclaim their history, heal their wounds, regain confidence, value their own culture, and stand up politically and socially for their rights within their communities. The problem is that everyone knows that change is necessary, but people do not want to leave their comfort zone and give up their privileges. Many people want change but are not willing to pay the price for it. But that is the only way we can create something new on both sides. When we talk about the younger generation in Europe—what do they know about this history? Nothing. They take the society they are born into for granted. Only when you know history and understand how your ancestors accumulated wealth will you see black people on the street differently. They think everything is self-evident—that they are the nicer, smarter, and more capable people in the world. The very fact that they live in their own bubble of truth creates this disparity.

Ibaaku: As he said, people need to understand how Africa is connected to Europe today. It is not just about the past—it is still ongoing. The coltan in our phones, the coffee we drink, or the chocolate we eat… All these big corporations are still in Africa, still exploiting what feeds Europe or the Western world. People need to realize that this is not just a thing of the past—it is still relevant today.

Alibeta: My focus is on the question of what responsibility we artists have. Because the task is immense. So, what is the role of artists on both sides? This is one of the questions we reflect on when we believe in the power of art—art as a force for change. And that’s why we focus on imagination. We believe that we must first resolve the question in our minds. Imagination can be incredibly powerful; it can reshape certain social structures or relationships. Alejandro Jodorowsky, a Chilean artist who has written extensively about generational trauma, would agree with me. The power of art lies in manifesting a new world—a world that one envisions.

Ibaaku: And also in how we manifest a new world. We must bring forth a new alternative, a new utopia, a new way of acting—to prove that it is possible.

Version: Interestingly, in this issue of Version, a young Chilean artist will be contributing. She explores ancient healing rituals and medicinal plants, but also digital utopias. In her work, everything is interconnected and influences one another.

Ibaaku: We often talk about elements as interfaces. For example, water is one of the most important natural interfaces in our culture. This idea of interfaces can also be seen in technology. But how do we bridge this gap? Spirituality or imagination is not something old or something that belongs to the past—it is still our reality here. It is still something that people use like tools, a technology. For us, it can also be a solution or an approach to a technological problem. We have these ideas of African technologies or the Wi-Fi of the spirits. All these concepts serve to build a bridge between modern technology and the history, culture or knowledge that is still alive here. But we do not yet trust ourselves enough to fully embrace it. That’s why people trust a cell phone more than a jug of water.

Alibeta: When we show people a screen, they believe what they see because they understand the logic behind it. It is a rational concept. But when our grandfather or uncle takes a bowl of water and says, “I can see what is happening there,” they are suspicious. Because they do not understand the rational possibilities behind it. African knowledge is the mystical knowledge of spirituality. So how can we connect all these different forms of rationality? This is a profoundly decolonial thought because the rationality of the mind is something that was introduced and imposed on the world by Europeans—but it is not the only rationality. How do you know that you are not just a human being? You are human, but not only that… You are the birds, you are the water, you are the plants, you are everything, and you are nothing. How can we teach people to understand that the mind is not the only thing that exists? We have seen the societies that Europeans have built with their logical, mathematical rationality, and we can see how fragile they are. Because when the mind loses control, they are lost. But when you live in a society where you understand the universe and have access to other parts of your being, you find solid ground.