Talk / Raw Material / Version 6

Raw Material Company was founded in 2008 by Koyo Kouoh. Originally from Cameroon, she studied bank administration and cultural management in Switzerland and France and at some point felt the need to return to the continent to develop and interconnect artistic and intellectual creation in Africa. First, she went to her country of origin and met Marilyn Douala Manga Bell who, together with Didier Schaub, founded a contemporary art center called doual‘art in Douala in 1991, where they worked with artists, developed residency programs, and realized site-specific artworks to promote the work of Douala artists beyond the country‘s borders. Since 2019, she is Executive Director and Chief Curator of the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa (Zeitz MOCAA).

When Koyo Kouoh arrived in Dakar in the mid-1990s, the ground was, in some ways, already prepared for her work. A lot had happened in cultural politics since the 1960s, thanks to former President Léopold Sédar Senghor and the art collectives that emergedafter independence. Senghor developed a whole series the demands of the Negritude movement and thus focus on an African aesthetic, such as the Ecole Nationale des Arts du Sénégal, the Manufactures Sénégalaises des Arts Décoratifs de Thiès and various other projects such as the World Festival of Negro Arts which is considered the forerunner of DAK‘ART, now one of the most important biennials of contemporary African art on the continent. So Dakar was the place to be.

But Senghor‘s cultural policy was always oriented toward the colonial power, France, and he did not succeed in breaking the social class dynamics engendered by the questions of accessibility and education. Even though many artists benefited from this cultural policy, they were, in a sense, made state-dependent during this period. It was the government that made selections, paid for their studies, and created various kinds of infrastructures that gave them the space to develop their artistic skills, especially after the structural adjustments under Senghor’s successor Abdou Diouf in the 1980s. There were, and still are, many art and culture professionals who see this as a kind of dictatorship over the arts and criticize Senghor for ultimately tying his political system and cultural policy to the French and thus to the colonial system.

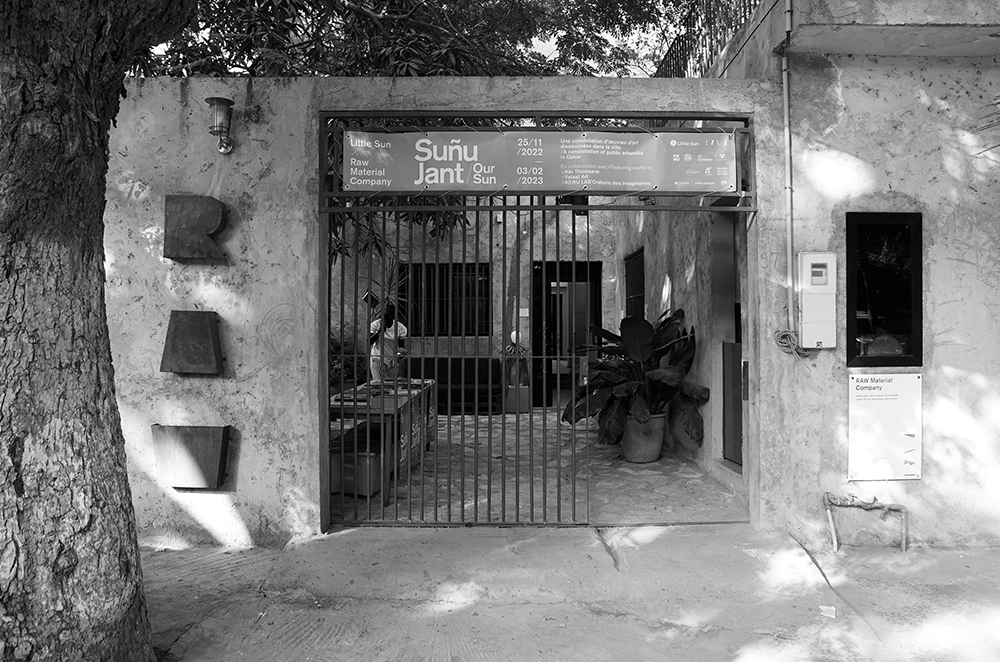

Version spoke with the director of programs, Fatima Bintou Rassoul Sy, the curator of programs, Delphine Buysse, and artist Ibrahima Thiam on the occasion of the SUÑU JANT exhibition during Partcours 2022 in Dakar.

Fatima: When Koyo came to Dakar, she found a city with many artistic spaces, exhibitions, collectors, but what was lacking apart from the artistic production was a space for critical thinking and writing based on artistic practice and its links to society an knowledge production. There were many artists living in Senegal who were challenging and criticizing this notion of negritude. Among them, Laboratoire Agit‘Art, 1974, founded by Issa Samb and Djibril Diop Mambéty, along with El Sy and playwright Youssoufa John. Their outlook was political and community focused, publishing manifestos and creating installations that raised issues about African contemporary society. And later, collectives like TENQ (1996) or Huit Facettes (1995) emerged from this.

The question arose: Who among the people living in Senegal, embodying this culture—understanding the work of someone like Joe Ouakam, himself so deeply rooted in the Lébou community—can do an art-historical valuation? At that time, it was important that our art history could be written by us, that most of the critical contents related to our work also come from our generation of artists and not be left into the hands of art historians who would project different prisms. That’s why Koyo founded the Raw Material Company. It is a center for art, knowledge, and society, an initiative involved with curatorial practice, artistic education, residencies, and the knowledge production and archiving of theory and art criticism. What structurally grounds Raw Material Company is our library that focuses on contemporary African art—also cultural politics, fashion, and architecture—and contains a film database. Every artist who comes here leaves books and other resources that we can share with the people who use the library.

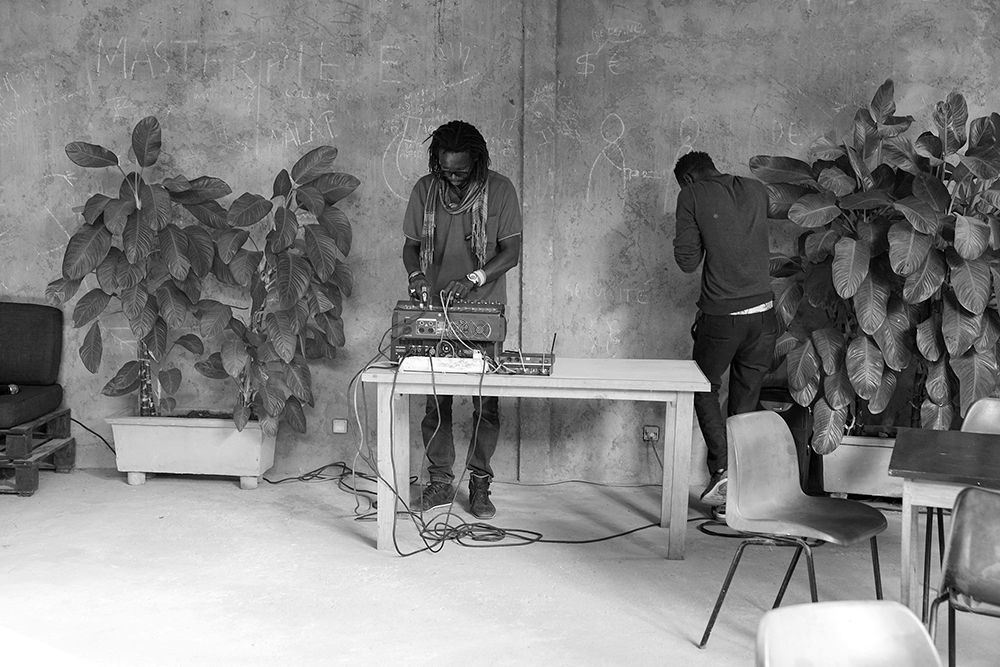

We have a place for exhibitions and a cultural program for the public that usually happens on Friday: Vox-Artis, which gives the opportunity to an artist or curator to speak about his practice, Raw Ciné Club, where we have films screenings and discussions, Citéologies, which addresses social issues related to the metamorphosis of megalopolis and specifically Dakar, and The Argument, which brings the discussion back into the middle of the room. And we also have a residency program (two research residencies and one production residency per year) through which numerous cultural practitioners and scholars of all disciplines have been joining us. Ibrahima, who has been working with us from the beginning, was part of our local residency program for artists who live in our area: artists who we work with, are interested in, and want to support in some way. His involvement brought us a lot in terms of research, resources, and connections.

Ibrahima: I was born and raised in Saint-Louis and everything started there, at home with my grandmother who was a dyer. I attended the French Institute in Saint-Louis at a very early age. When I came to Dakar, after my high school graduation, to study economics, I became interested in art. I wanted to enroll in the École des Beaux-Arts for photography, but unfortunately there was no course for it. So I learned a lot from books and cinema. At some point, I understood that I could look at photography as something artistic. At the very beginning of Raw Material Company, in 2011, there was a symposium with a lot of creatives, art historians, artists, and other institutions, and they were talking about art and a kind of alternative education. I found that very interesting and from then on I followed everything. RAW, for me, is an institution for society, something that is open to everyone.

After my residency, I made an exhibition called D‘une rive à l‘autre, during Partcours 2020. Actually, I had already started this work in Saint-Louis. There are many legends and traditions about Mame Coumba Bang, a water spirit accompanied by many rituals. Everything that lies between the visible and the invisible, these things interest me in my practice. After that, I did a work on Maam Njaré Jaw, another Lébou deity of Dakar, and during the stay at Raw Material, the idea arose to continue this research with another deity living in the Lébou community of Ouakam. The idea was to show this syncretism between the religious side, animism and the Muslim religion. And at the same time, Raw Material is a project that is interesting because there were collaborations with other artists who were also interested in exploring the Lébou community.

Delphine: When we have artists in residence, we prepare a corpus of resources according to the research they are leading. It means a bibliography but also a list of people who can support them in pursuing their research whether they are from the academic sphere or not. They can be connected to art, culture, politics, science, or any other non-academic sector. We go on a journey with the artists, to weave a web around their work and contextualize it. RAW also organized three symposia out of which three condition reports were born. These were key moments for many artists and cultural actors in Africa because they brought together theorists and scholars, not only from the continent, but also art historians from the diaspora.

We take an international approach that responds to local social, sociological, and cultural realities and we try, with our artists and art theorists, to think of how to respond to the needs and desires of the context. It’s this kind of critical method that RAW has brought to the contemporary scene, not about responding to external injunctions such as the market, but going back to human beings and society. It also starts with questions of philosophical aesthetics, when you know that here in Senegal a lot of artists don‘t call or define themselves as such. They say that they‘ve been appointed artist by the community and chosen to take on that role. It’s not simply about the dichotomy of what it is to be an artist abroad and/or in Senegal. Here, collectives are a historical reality. How people navigate the system to create forms of cooperation, I believe, is much stronger in Senegal than in other African countries. That‘s why there are also many artists here who can practice multiple media, the boundaries between disciplines are not straight lines.

Version: So for you, knowledge production and educational work are central concerns. You use methods that are also used in the Western art world, such as archives, libraries, cultural exchange and residency programs. Wouldn‘t there traditionally be other methods of knowledge transfer in Africa that could be integrated?

Fatima: Of course there are. But we are fundamentally against the idea that, since we are an organization based on the African continent, we should use only traditional learning or transmission methodologies. As if there was an opposition between authenticity and contemporaneity. What is meant by this is that the development of our programs and their articulation take into account the specificities of the context in which they evolve. This means that we do not create any hierarchy between the forms of knowledge that we invest or put into perspective in our curricula.

Delphine: RAW Académie is an experimental residential program for the research and study of artistic and curatorial practice and thoughts. It nurtures a desire to be a generative space for transmission based on knowledge sharing and collective experimentation following an organic rhythm. It begins with a recontextualization in space and time, which then allows for decontextualization, regarding other forms of learning—non-academic—where inherited, transmitted, or even non-palpable acquaintances coexist. This implies breaking out of hierarchical frameworks and maintaining a space for criticism and self-criticism of the sources or methods of education, and where the notions of break and failure also occupy a predominant place.

Version: We talked to some artists here, about what African art can actually be, whether it really exists. A big difference to Western practice seemed to us to be the communal practice and social engagement that art takes on at social functions.

Fatima: We are not fixed on a contemplative relationship with art. We believe that art can change society in terms of political attitudes, social engagement, and social values. Laboratoire Agit‘Art‘s practice is focused on happenings, on creating dramaturgies and artistic settings in which the community can be involved without needing training in art or philanthropy. I mean what we do is anchored. We deliberately publish French and English to remove the barrier between Francophone and Anglophone Africa and create a space for many people of African descent to convey. The idea is to connect us all through what we think, what we develop, what we write. We also try to broaden our spectrum as much as possible and learn from collectives or artistic institutions in Africa, Southeast Asia, South America, or other places of the so-called “Global South” that are facing the same challenges and/or issues when it comes to the development of the artistic field and practice.

Version: We talked very often in Dakar about this question of mutual learning; that

we from the European countries should also learn something from the so-called “Global South.”

Fatima: It is not a question of South versus North but more about the network we have built over the last ten years thanks to RAW team’s and Koyo’s work. She has navigated in many different countries, but she was specifically engaged in Dakar. What she has never forgotten is that certain debates need to be relevant for us first, to be engaged and undertaken by the very people who are working on a daily basis in our geographies. Those people who see, live, build, write and enlarge the understanding we have of our history, our memory, our myths, so that we are ready to face actual challenges. Especially when you know that in Europe in the 1990s there were many exhibitions on contemporary African art made by people who didn‘t know the continent and the artists they were talking about. At that time, the voices of the African critics and arthistorians, who had been doing amazing work for years, were also disregarded.

Delphine: The initiatives here have made it their mission to fight against certain projections on the continent. Of course, it was a need to reappropriate knowledge and write about it, but another issue we can face is that we are confronted with a kind of extractivism of knowledge. For example, we see many projects coming to Senegal or to Africa with beautiful intentions of exchanges when the meaning of what is an exchange is actually very different.

Version: Raw Material Company also cooperates with European institutions such as the Haus der Kulturen in Berlin. What aspects are important to you in these collaborations?

Fatima: There is a kind of tendency toward African art and the African continent. The thing is that people have been working here for years before anyone came to learn from them. There are some Western organizations that are aligned with us on how we engage with history on the continent or in the diaspora. We work with these organizations with which we create lines of convergence. This does not prevent us from remaining attentive to the power dynamics that these collaborations can create. There are quite a number of institutions and scholars who think and reflect on colonial issues and structures of exploitation within educational frameworks. But here on the African continent they are not noticed because we don‘t have the infrastructure or the educational opportunities to promote these reflections on the ground. We create different paths where this reflection can take place. We go to every conference we are asked to go to and extend the invitation to our fellow colleagues, as long as the invitation we receive is a way to respond and achieve our goal.

But what matters most is that on a daily basis our young people can push open the door of RAW and find everything they need to drive and develop their ideas.

Version: Can you tell us something about the current exhibition, which is about sustainable projects and the collectives working on this topic?

Delphine: The exhibition was a long process as Little Sun, Olafur Eliasson‘s foundation, has been collaborating with RAW for many years. They created their first exhibition here in Dakar in 2013. This time, they both wanted to create a project in public spaces with art and solar energy and open up the discussion about climate change justice. So, they decided to invite three organizations or collectives dedicated to community projects to participate. These include Yataal Art, which deals with cultural heritage in Dakar‘s medina and is known for a specific development of practices linked to urban cultures but also permaculture and environmental sensibilization; Kër Thiossane, which is known as a center working on art, technology, sciences and societies, and especially around digital art and deepening the question of commons; and Kenu, which is gathering the Ouakam community through community-based projects and special attention to living arts. In the Raw Material Company exhibition, we have created a kind of synthesis of what has been done in the other structures and an evolutive map of initiatives and collectives that are developing in Dakar and Senegal and are committed to protecting the environment.

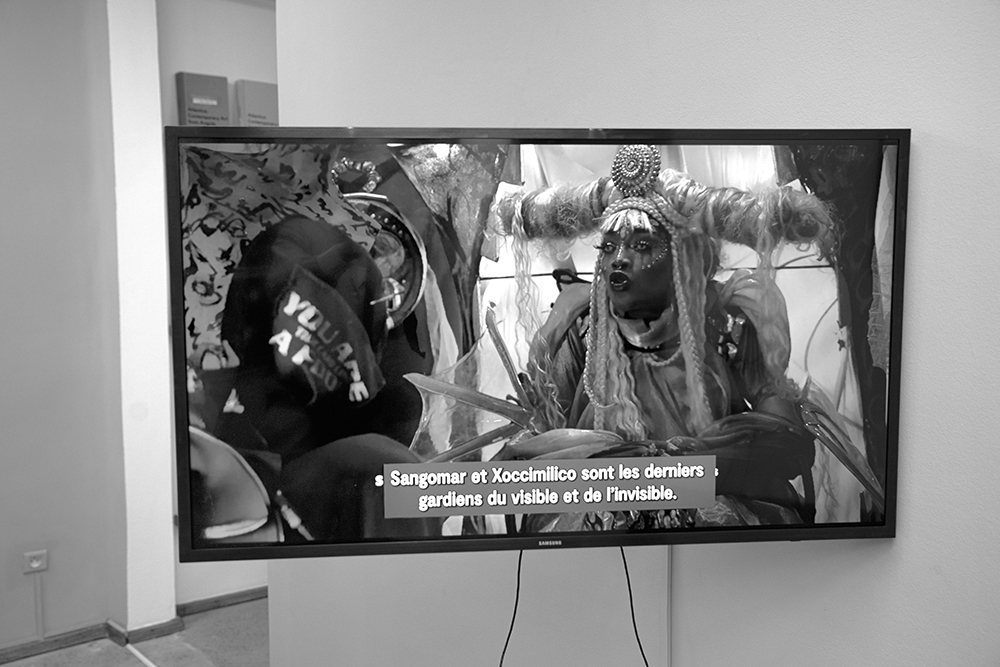

Fatima: Over the years, we have carried out various projects and residency programs that address this issue. In this exhibition, we present two videos made during the Fast Forward by Little Sun project. We were invited to select artists or filmmakers to make a film about climate change. Selly Raby Kane‘s film Jant Yi is set in a dystopian Dakar where people must generate electricity from the energy in their own bodies. This film is about the inner conflict of extracting existing oil in an area called Sangomar, but at the same time destroying a sacred place where we have buried spirits and ancestors, thus a cultural heritage. The second video is the animated film Possible World by Ezra Wube. The film was inspired by interviews with over one hundred everyday people in Ethiopia. Wube brings to life his interviewees‘ dreams of a regenerative world that begins with existing practices that benefit both communities and the environment. The third movie was made by an artist from the RAW residency program, Shezad Dawood. Titled Leviathan Episode 7: Africana, Ken Bugul & Nemo and filmed in Dakar, it is part of a series of episodes in which Shezad questions the kind of society or world we want in the future. In the films, shot in different locations around the world, he interviews anthropologists, sociologists, biologists or activists working to preserve the goods of the community.