Interview / Yasmine Eid-Sabbagh / Version 6

Version: You studied history, visual anthropology, and philosophy, and then lived and worked for a long time in Burj al-Shamali, a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon.

Yasmine Eid-Sabbagh: I studied history first, then photography, and in 2001, I traveled to Lebanon for the first time with a friend. We were interested in the history of the Middle East and the reality of refugee camps, which have existed since 1954. In 1948, many Palestinians were displaced. They waited for several years behind the border, hoping they could return. After four or five years, the administration started setting up refugee camps and distributing people. We had a small research travel grant and spent several months working photographically with children from the refugee camps. We received a lot of feedback from the children about their life realities, and they asked us countless questions. In the context of my master’s studies, I returned in 2005. I set myself the task of finding out how to work with the residents of Burj al-Shamali in an ethically sensitive way using photography as a medium. There are often abusive dynamics in participatory projects. Even if the gaze seems to reverse, with cameras distributed to the residents with the request to document their own lives, the photographs are usually selected later by the photographer. Often, there’s little exchange with those who are in or made the photographs. People are essentially used to gain access to private spheres that would otherwise be inaccessible. I wanted to develop an alternative way of working collaboratively in a photographic project, addressing and making visible the power imbalance. This has now become a nearly 20-year-long project, continuously evolving through different phases. The latest phase is the negotiation process around the photo archive we’ve compiled, which focuses on how we can create an image archive that’s not necessarily publicly accessible but still gives it a form of existence. How can we hear, read, feel, or taste these images instead of just seeing them, since there’s resistance to showing them publicly? And that’s exactly what we experimented with, for example, at documenta.

Version: And this resistance comes from the people in the refugee camp?

Yasmine: The resistance partly came from the people there, and it was taken up by me and others, who are currently managing the project. The resistance was already linked to the initial gesture of handing images over to the archive or collection, where the residents of Burj al-Shamali or the project participants made the submission of an image contingent upon certain conditions. It wasn’t really about documenting current life, but more about looking at and understanding already existing images together. In discussions about the images, different conditions emerged for each image, regarding whether and, if so, where and how it could be shown. The collections within the archive are of varying sizes. Some collections include only two or three images contributed by someone, while others contain hundreds or thousands. In exchanges with the people – and this was actually the most interesting part of this process – it was important to understand what they thought such a collection or digital archive could be good for. It wasn’t about creating access to the images anymore, but about understanding their relationship with the images and how they approach photography, how they conceive of photography, and how they engage with it.

Version: How big is this archive, actually?

Yasmine: It’s not as big as you might think. The active collecting phase took place between 2005 and 2012, and since then, hardly any new images have been added because there’s no one there to add new pictures or collections to the archive. A lot of the process is tied to me, which I now find problematic. Collecting is not automatic or programmable. It’s very much about yourself and the way you speak to people and interact with them. For example, I went to some people for tea over a period of two or three months to drink tea and talk about pictures or anything else before these pictures even made it to the table, because often it wasn’t so much about the pictures themselves anymore.

Version: Is there a difference between old pictures that tell family stories or other significant experiences, and the digital flood of images on phones? This flood of images always has an affirmative quality, as we feel like we already know so much, and this image becomes a constant.

Yasmine: It is quite clear that these were the treasures that people had at home. many of them hardly had any photographs anyway. When I first became interested in photography there in 2001, digital photography was not as widespread. Members of wealthier families, who lived outside the camp, had visited and taken photos or brought cameras with them. These were the families who really had photos from the 60s, 70s, and 80s. Then there were the photos from itinerant studio photographers who came to the camps to take pictures. The first studios in the camps didn’t open until the 90s, so before that, photography was always associated with the outside world, and not everyone could afford it. There were these typical family photos where you’d always see the mother with all the children or anyone who depended on the household. They were often attached to a document because they needed these images to show how many people were in the family to calculate how much rice, lentils, oil, and so on they could receive. There are very specific photographs that keep appearing, like portraits of young men who, at 18 or 19, had Lebanese citizenship in order to go into the military. My experience in Burj al-Shamali set off a process for me that deconstructed everything I had learned about photography. What photography is, how it works, how to make good photos, how to handle them, how to display them—it’s all totally dismantlable. Today, I have a completely different relationship with photography, and I approach it very differently.

Version: At documenta, you showed (or rather worked with) images from the collections of Burj al-Shamali in a specific framing.

Yasmine: The focus of documenta wasn’t necessarily on exhibitions or a final product. Instead, there was the opportunity to focus on processes. I am regularly in Lebanon – also in Burj al-Shamali – and have individual conversations with people there. But it was the first time that there was an opportunity, and specifically funding, to gather everyone involved and spend time with the collections, engaging with them. We met regularly in preparation for documenta to work on our project. Two methods emerged: one was a culinary materialization of the archive, and the other was a sound materialization of certain collections. The group included residents from the camp, some former residents now living in Europe, and Nailé Sosa Aragón, a Cuban musician we worked with when it came to materializing the images in sound. One starting point was my PhD, which is divided into different sections in the form of scripts, essays, or other formats. We took out an item, read and criticized it, took it apart, rewrote it, etc., a kind of re-reading of parts of my PhD. Through this, we came to specific images or collections. The other entry point was directly through the collections. Since we wanted to materialize them through food, it made sense to look at what they offered in terms of food, food production, or food distribution. We were on site in Kassel for four weeks, discussing specific questions every day and then trying to implement them musically, and then continuing to discuss the results: How does it sound? What emotions does it provoke? Does it work with what we discussed before? It was a process, a collective attempt to make things visible through discourse.

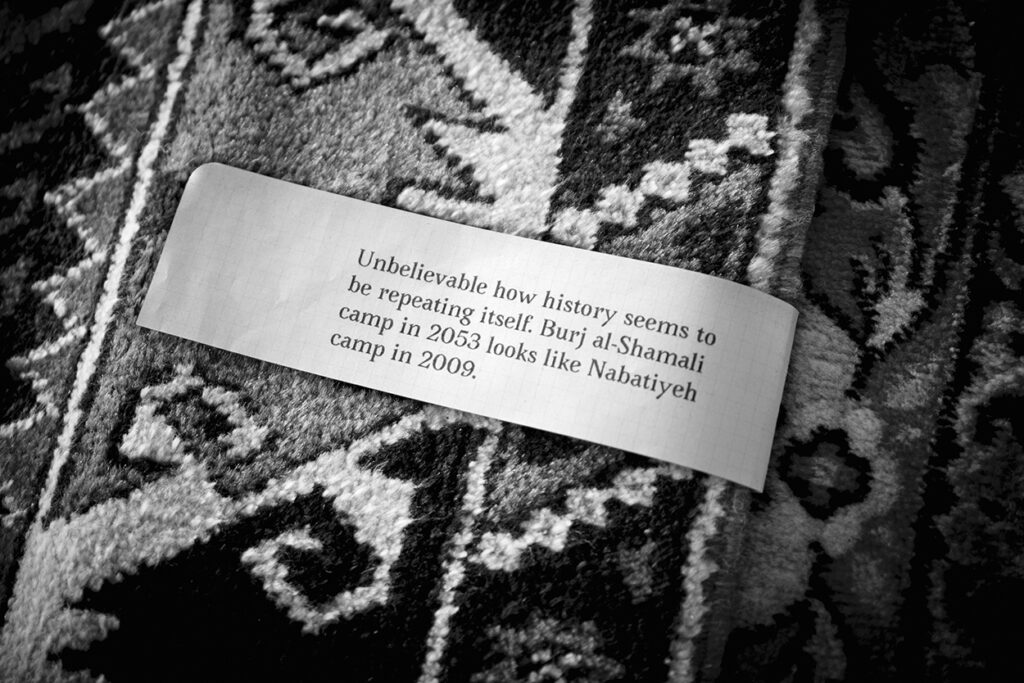

We had a lot of closed sessions, but later we allowed the public into the materialization process. Visitors could sit in the room and listen. At times, we sat next to them and whispered things in their ears, just to give them input and connect them to what was happening immaterially. This led to snippets, which were placed on the floor between the carpets. These were excerpts from conversations or moments of exchange. When we weren’t around, people could listen to the music and read the notes, getting indicators of what the process in that room was about. After six weeks, we created a sound installation that could be visited continuously. Unfortunately, the room was closed for some time because documenta had issues with supervision staff.

Version: As a participating artist, how do you assess documenta’s handling of the antisemitism allegations? The scandal, which was heavily exaggerated by the media, sadly overshadowed the actual aim of the last documenta and turned the underlying demand of ruangrupa—namely, to listen to each other and learn from each other—completely upside down.

Yasmine: Two worlds really collided. From the documenta institution’s side, there was little energy or understanding that more was needed than just the minimum institutional services. They had difficulty adjusting to the situation where not only works were being produced and presented, but discursive processes were supposed to take place within collectives. For example, it was predictable that many more people would be on-site than usual. They were completely unprepared for that—no staff, no planning. There were issues with racist attacks and accusations, and documenta was unable to respond appropriately. Listening wasn’t possible. While artists spoke about creating „safety“ as a collective, because you watch out for each other, respect differences, and engage in a way that allows everyone to feel safe, documenta responded with „security.“ There was a meeting with the police and the mayor of Kassel, where the police chief said, “In your countries, I understand you’re afraid of the police, but here in Germany, the police is your friend and helper.” That was the line of argument, and it was just very, very sad to see that it was impossible to make any progress.

The documenta is an on-and-off institution that swells every five years with a large number of employees working under precarious conditions, only to then be scaled back to a minimum workload. Even though the documenta has existed for 70 years, there seems to be no continuity, no institutional learning from one edition to the next—not even when it comes to issues of gender, discrimination, and racism. There are no anti-discrimination or equal treatment procedures. They were simply incapable of responding, and truly terrible things happened that should never have occurred.

Version: Were there racist incidents by employees and the institution?

Yasmine: Yes, and a downplaying of racist incidents that had occurred in the lead-up to the documenta, whether by the Kassel police or other groups, as well as incidents that happened during the documenta itself. Things simply weren’t taken seriously, and incidents weren’t followed up on.

Version: One of the troubling aspects of the whole discussion is that the selection committee has barely spoken out and backed ruangrupa.

Yasmine: I would say that many have not fulfilled their responsibility. I think one mistake we, as artists, might have made was not packing our bags and leaving at the beginning. We didn’t want to destroy the hope for possibilities that so many people had brought with them from all over, just because there was this political conflict with the documenta. There was endurance and generosity on the part of the artists. We organized ourselves while continuing our work. The organizing ranged from anti-discrimination working groups to communication working groups to hosting working groups, and so on. There were thousands of working groups, and we tried to find a shared stance through the statements that were published. Still, there is so much that needs to be revisited—simply to understand what these dynamics were, who ultimately benefited from them, and who once again did unpaid labor and ended up completely exhausted.

Version: Perhaps a discussion process has been set in motion that can shed new light on these issues. How does a perpetrator nation like Germany come to claim moral authority over antisemitism and essentially engage in a reversal of guilt? The term „Global South“ itself should also be questioned as an exclusionary construct.

Yasmine: Playing off racism and antisemitism against each other as competing forms of discrimination is simply unproductive. Germany refuses to further examine the interdependence between racism and antisemitism. This became visible in the context of the documenta and can also be observed in various places in German media today. The academic committee that the documenta appointed, which functioned more like a censorship committee, adheres to the IHRA definition of antisemitism. And the fact that this is simply accepted in Germany as if it were truly a legitimate definition—despite it being widely considered problematic outside of Germany—is something that can hardly even be discussed there. That is precisely why additional definitions of antisemitism have been developed, with more concrete examples, to counteract the instrumentalization of the term.

Version: You now live in Senegal, in Dakar, where you have created a kind of space that appears closed from the outside, like an island, but also has a certain openness and connects you to the surrounding community. Can you talk about this place, how you and Adrià Ramírez Mena run it, and why you chose this location?

Yasmine: Originally, this place came to life because we have children, and it was important to us that they have nature around them. Dakar is a loud and lively city with little space for children. We previously lived in Spain, where the kids grew up in nature, and we started an educational project there—Ses Milanes – créixer a la natura, a self-organized forest kindergarten that uses nature as its infrastructure. When we came across this house—at the time, it was in poor condition—we saw that it had a huge garden, was close to the sea, and offered a lot of space. We thought this could be an opportunity to extend our pedagogical practice and create a space where different forms of being together, critical thinking, and action could come together. But when you embark on something like this, it becomes a real effort—basically, another project, though we never conceived it as one. It’s just our way of living.

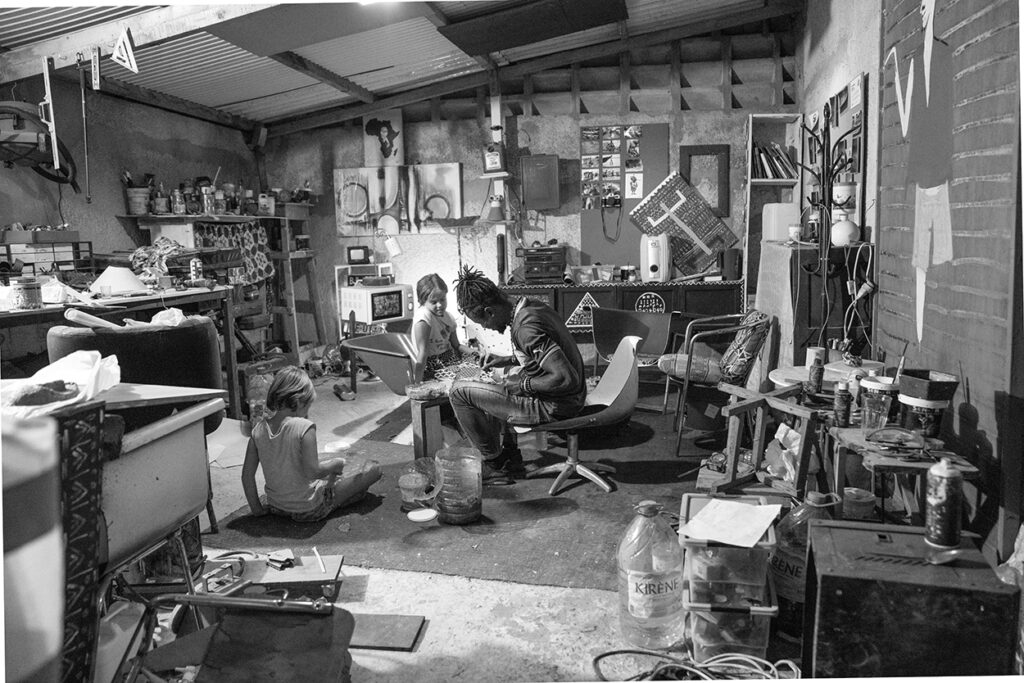

It took on a life of its own because people approached us, asking if they could use the large space downstairs. That’s how an exhibition for the last Dakar Biennale took place here. Then there’s also this old garage—one evening, we were talking with a friend about his work and realized he didn’t really have a space to work in. So we offered him the garage. He’s very well connected with many artists from the region—Mali, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea, and so on. As a result, we’ve been meeting more and more artists, broadly defined, who are trying to sustain their practice and make a living with minimal resources.

We have a lot of space here, and we share it. Sometimes events or exhibitions take place, and those who can contribute put something into the renovation fund or fix things themselves. It’s a very informal space. A lot of people already know about it, but it’s not an institution, and for now, it’s not meant to be one. It’s interesting not to have to think about formalizing it, but rather to see how it evolves as artists and others take ownership of the space. A younger group of dancers and acrobats recently came and asked if they could use the garden for vertical rope workshops with children. There’s also a group of women who create various handicrafts and plan to exhibit and sell their work here in March. That’s how it’s meant to continue for now—those who understand what’s happening here should join in, and it should collectively self-organize. Not in the sense of a labeled „collective,“ but rather as many different individuals who, through their presence, form a kind of collective.

Version: Even if you define the location, because that’s what it’s tied to …?

Yasmine: Absolutely. These are just processes. Right now, I’m just observing, and I’m quite happy about that. It’s also just nice to be in a different context again, even though it’s challenging for everyone here in Senegal and the surrounding countries to find ways to make art reach somewhere.

Version: It’s a challenge to break away from the perspectives that have shaped us. We judge everything through a European lens. The Western neoliberal art market focuses on works or brands, whereas art here clearly serves a different function.

Yasmine: It’s more about the process—being in exchange with all these people, listening to their experiences in making, studying, and producing art, and building connections between art and everyday practices in order to have an impact on society. And that constantly raises new questions that are relevant to me.