Interview / Barbara Kapusta / Version 5

We are the sleeping, the walking, the giants and the artificially intelligent.

We circulate

our moist material.

Dripping and oozing.

Let it be used and taken, changed

and adapted, given away freely.

Ours is yours to share and spread.

(Excerpt from The Leaking Bodies, 2020)

Version: What is striking is that your work repeatedly revolves around the dissolution or questioning of established dichotomies—such as machine–human, density–permeability, gender dichotomies, and so on. Can you explain this in more detail?

Barbara Kapusta: For me, the interesting point is the moment when these dichotomies vanish when we think about concepts in broader spectrums. Take, for instance, the terms human and technology: first of all, these aren’t concepts that stand in opposition—the machine grows within us (and replaces our organs, expands our bodies, we are all technobodies) and we are the ones who have to deal with machines (control them, invent them, operate them, etc.) Secondly, the concept of human is not an original one; rather, like the concepts of nature, biology, and technology, it is shaped by our Western, European, bourgeois, secular (formerly sacred), and ultimately capitalist culture.

In consequence, if, as Jean-François Lyotard (1990: 81) has noted, the “Greco-Christian Occident” could not, and cannot, conceive of an Other to what it calls God, this characteristic was to be carried over in secular terms as the humanist intellectuals of Renaissance Europe replaced the earlier public identity Christian with that of their newly invented Man defined as homo politicus, and, as such, primarily the political subject of the state. It was therefore to effect this secularization of its public identity by over-representing both its first variant of Man, defined as political citizen and/or subject of the state, and, from the end of the eighteenth century onward, its second variant of Man—defined in now purely secular, because biocentric, terms as homo oeconomicus, and, as such, primarily as the Breadwinner/Investor subject of the nation-state—as if each such definition of Man were at the same time definitions of the human itself. In consequence, the intellectuals and creative artists of Western Europe were able to bring together their hitherto theo-centric notion of Christian and that of their now-secular notion of Man (in its two variants) into conceptually different notions into the contemporary world of modernity, both in its dazzling triumphs and achievements and in its negative underside. But they were able to do so only on one condition: that they would make their culture-specific notions of Man— both in its first still partly secular and partly religious form, and in its now purely secular, because biocentric, form (i.e., one whose origin was now narrated as being in Evolution rather than as before, in Divine Creation)—into notions that were and are ostensibly conceptually homogenous with the reality of being human in all its multiple manifestations. With this, they were thereby making it impossible for themselves to conceive of an Other to what they called and continue to call human.

(Sylvia Wynter, “On How We Mistook the Map for the Territory, and Re-Imprisoned Ourselves in Our Unbearable Wrongness of Being, of Désêtre: Black Studies Toward the Human Project”, in: A Companion to African-American Studies, Ed. Gordon, Jane Anna, Gordon, Lewis, 2006)

V: You are referring, among other things, to the concepts of Donna Haraway and Sophie Lewis, who engage in scientific-technological speculations about fundamentally restructuring communal life.

BK: Yes, the texts by Donna Haraway or Laboria Cuboniks, Helen Hester, Paul B. Preciado’s Testo Junkie, and indeed Sophie Lewis’s book Surrogacy Now all engage me. They represent societal and political theories and positions that are necessary beyond art.

V: So the basic idea is that once we become hybrid, societal determinations dissolve, or on that basis, utopian models can develop more freely…

BK: “The closed self-organized body is at best a working fiction.” This quote from Jane Bennett’s book Vibrant Matter captures it quite well I always ask myself why it should be so utopian to be able to decide for yourself who you are. Why is systemic change considered so utopian? Why is it so utopian to think of one’s own body as fluid and multiple, even though it exactly is that? We live in symbioses with bacteria on our skin, in our digestive system. Pregnancy is a transformation, just like growing up, aging, or being ill. We live in communities and in dependencies. We are never just a single body.

While the fantasy of “blood” relationality is that it makes adopting one another unnecessary, in reality, as I sought to argue in the book, children never belong to us, their makers, in the first place. The fabric of the social is something we weave by taking up where gestation left off, encountering one another as the strangers we always are, adopting one another skin-to-skin, forming loving and abusive attachments, and striving at comradeship. Kinship, in other words, is always made, not given. By the same token, where kinship is assumed, it fails to be made, more often than we think. I’m with McKenzie Wark, therefore, when she proposes reviving the ancient word ‚kith,‘ with its nebulous senses of the friend, neighbor, local, and the customary; when she suggests the comradely rewrite of Haraway: “make kith, not kin!”

(Sophie Lewis, “Mothering Against the World: Momrades Against Motherhood”, in: Salvage, September 18, 2020, https://salvage.zone/articles/mothering-against-the-world-momrades-against-motherhood/)

In the foreword to The Left Hand of Darkness, Ursula K. LeGuin writes: “I write science fiction, and science fiction isn’t about the future. […] I’m merely observing, in the peculiar, devious, and thought experimental manner proper to science fiction, that if you look at us at certain odd times of day in certain weather, we already are. I am not predicting, or prescribing. I am describing.” Future visions are descriptions of our lived realities that help us understand those realities and formulate critique. The potential of such descriptions of the present is that they allow us to think utopically and perhaps even wish for something better for our current world.

V: Does that essentially mean that everything which can occur within a fictional realm of imagination, is in some part already reality at that moment?

BK: Ultimately, my texts are descriptions. I describe things that I observe—phenomena, images, textures, and ultimately emotions and physical states—that catch my attention. I’ve never felt the need to invent something that doesn’t yet exist; but rather I put things together that perhaps don’t belong together directly.

Heavy and clumsy, she pauses. Blurred are her balance and symmetry; blurred are her features. On her surface cuts, scrapes and cavities for ingestion and emissions enlarge. We see hyperbolized body parts, spiders’ legs, arms, fingers, fingernails, her mouth and lips, genitals, the eyelids. We see limbs, but her center is absent.

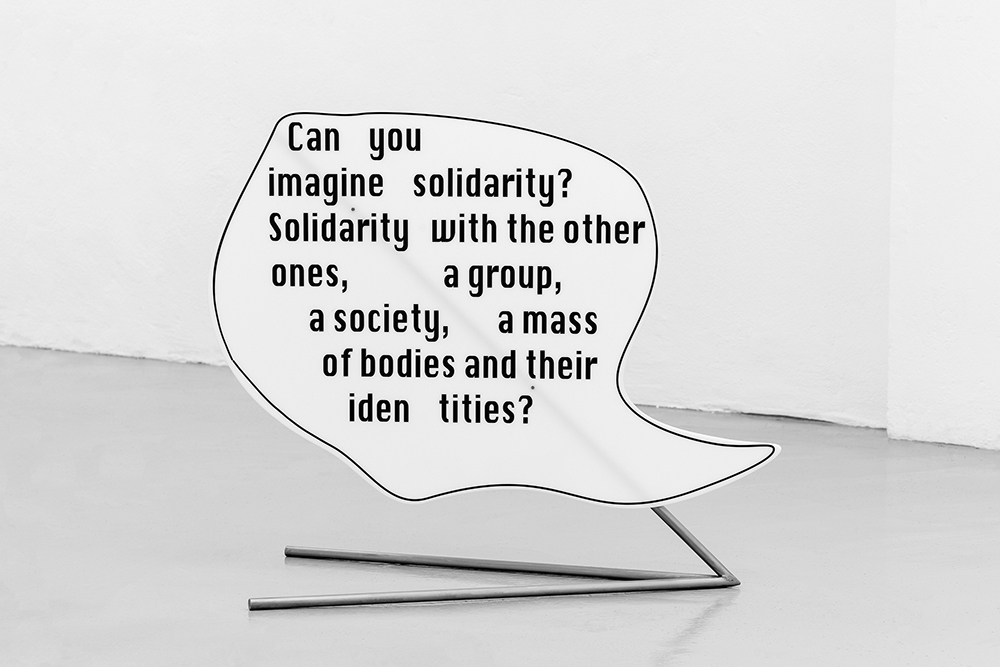

„Becoming giants,“ she now mumbles quietly and with ease, „we know our body only in parts. We have to bend in an attempt to see, leave the center for the periphery. „ She rhymes sometimes, but then she continues seriously: „Can you imagine solidarity? Solidarity with the other ones, a group, a society, a mass of bodies and their identities?“

(Excerpt from The Giant, 2018)

V: Is this also how your texts come about? There are whole books in which they are arranged in the same way as in concrete poetry?

BK: Often, it’s like the direct speech in comics—a blending of the form of speech bubbles with the corresponding emotions of what’s being said. I am fascinated by making language visible. In the Mixtec codices, for example, language is depicted as a speech bubble, while song appears as a speech bubble adorned with petals. A beautiful book on concrete poetry that impressed me greatly is Women in Concrete Poetry: 1959-1979, published by Primary Information in 2020. It features works by, among others, Giulia Niccolai, Ruth Jacoby, and Silvia Trevales. It’s very inspiring to see these different works together like that.

(,

now we are moving,

animated bodies.

Yes, O

we change our

sizes and shapes.

We can become many,

and sets of things, groups

and ensembles of

( and O

) C C

O

O

(Excerpt from The ( and the O, 2016)

V: In Empathic Creatures you also use linguistic signs and ceramics that you animate—almost as if you’ve written the text directly onto their bodies. In a way, you’ve brought them to life through the text.

BK: At some point, I started thinking about how to break the body down into smaller parts—into gestures, touches, descriptions—so that it no longer needs to be considered as a whole when you actually want to talk about much more concrete things. That’s how the ceramics came about. They could then speak, communicate with each other, and touch one another. In this way, worlds emerged where these figures—the O, the U, the eight, the hand, the bracket—come together.

THEY CALL IT

BROKENNESS.

THEY ARE THE

8, THE FIST,

THE MOLD,

THE BODY PART,

THE O, AND ALL

THE OTHERS

THAT REUNITED

AFTERWARDS.

AFTER SPEECH

ERRORS,

MUMBLING AND

CURSING,

BARKING AND SNARLING

COINCIDED WITH

FAILED

POLITICS.

AFTER BROKEN

BODIES, TRASH AND

CHUNKS OF ORGANIC

MATTER ALIGNED

WITH SCARCITY AND

MELTED INTO A FINAL

CRUSHING,

POLITICAL,

TECHNICAL, AND

ENVIRONMENTAL

BREAKDOWN.

(Excerpt from The 8 and the Fist, 2017)

V: Your texts feel somewhat apocalyptic to me, but there are recurring passages that critique society and capitalism, which could also be read as a kind of manifesto. There are also these speech bubbles that stand freely in space like objects.

BK: I often start from an imagined moment after the collapse of a system—one that somehow reflects our future, our past, and our present all at once. The construction of borders, the exploitation of humans and animals, of plant and mineral resources. My characters meet in these exploited places, stranded and affected, with no refuge, searching for accomplices. They remember the collapse and they remember the disappearance of solidarity and empathy. They have to explain themselves—their attitudes and responsibilities—if they want to enter into dialogue with one another. That sounds pretty exhausting now, doesn’t it? But at the same time, there’s a lot of closeness, gentleness, and tenderness. I also think about the ability to empathize, to step into bodies with needs different from my own. How can a skill like empathy be practiced? Or: how do we deal with conflict, competition, and harm? It’s not just about intact bodies. What about bodies that are wounded? And how can we imagine the body as a multiple, shifting, collective being?

That’s why the language is both brutal and tender. There’s a hint of ambiguity—we don’t always know whether an action carries a positive or negative connotation. The conditions are always shifting: belonging and discord, brutal and sensitive gestures alternate. Bodies form alliances and are then torn apart again by larger forces. It’s about a form of community that can just as easily fall apart.

i camouflage 20% of my body

with parts of yours

we move together

simulated technical creatures

kin critters friends

and family

elastic bodies of many kinds

a society

of empathy

(Excerpt from Empathic Creatures, 2018)

V: You often work with ceramics, which as a material has something very ambivalent about it. On the one hand, when it’s unfired, it’s fluid, in motion, and malleable, but once it’s fired, it becomes hard—the complete opposite, really?

BK: Many of my pieces that have distinct curved forms are made of porcelain. It’s very pliable, yet at the same time extremely brittle. Clay is much more pleasant and easier to work with, but it’s also quite rigid. I fire my works at very high temperatures. The material then bends very strongly and shrinks, and also cracks. The pigments I mix into the raw material develop very intense and vibrant colors at these high temperatures. I think it’s brutal work. The force exerted on the wet material, the drying process, the extreme heat during firing. And then, the things I make end up resembling something soft again, seeming flexible. It’s almost as if I want the ceramic to do something that it can’t actually do.

V: These objects are amorphous body parts but also elements of language.

BK: I started working with linguistic symbols related to bodies. The O is both a sound, an exclamation of surprise, the shape our lips make when we say it—you can also form an O with your hand. The C is like a bracket. Then I added the fist, and finally the hand, which appears as an animated figure in Empathic Creatures (2018) and The Leaking Bodies (2020), or as platinum-luster glazed ceramic works like Hand (Upright) (2018). The hand is the tool we use to grasp our world. It’s a signifier for our body and for the central way we interact with technology, reflecting our unease with our own physicality.

V: In your films, like Dangerous Bodies (2019), you animate these fluid objects—bodies or body parts—that are constantly changing shape. They take on something uncontrollable, somewhere between human and machine… Why are they dangerous?

BK: That would be manifesto fiction, I think—the resistant body that behaves differently from the normative one. There are many bodies people are afraid of—groups of people, unfamiliar bodies, bodies that behave in non-normative ways. That’s what I’m referring to. In the text, the characters call themselves: “We are the dangerous bodies.” That idea actually started with The Giant (2018): “See my hands becoming giant! Are you terrified of my fingernails?” So this body is gigantic and you get scared of it.

V: You mention mutual contamination at one point—we are entangled, contaminating each other and ourselves, also in an ecological sense.

BK: Leaking Bodies Series (2020) was built around this idea of leaks, contamination, and membranes. I mean our skin, of course, but also national borders, the ground, the transport networks for fluids like crude oil and water that cross private land, continents, and oceans. We also leave traces of COVID-19 mutations in our groundwater. The basis of our coexistence is our leakiness, our permeability, but at the same time, it’s under threat from the leaks of neoliberal finance capitalism, its infrastructure, and its machines. Despite all that, I keep thinking about and remembering the possibilities that lie in this permeability. A leak can also mean community, care, and relationships. “What is being spread?” asks the voice in The Leaking Bodies—and it doesn’t just mean harmful substances, but also something collective, something that can be shared and spread without fear.

Sophie Lewis is also concerned with the fact that this mutual contamination is absolutely necessary in order to be able to think of a community of solidarity at all. And it’s about the direction we want to move toward. When it comes to technology: how do we turn it into a tool for community—not a capitalist one, but something else, something that could come after?

V: Do you have a vision of what that community could look like? It would have to be something else—not anarchist, not communist, not democratic either. Is there a term or an idea you have? Would feminism still even be a category? If all dichotomies dissolve—purely utopian—if we had this fluidity with all beings, would we still need feminism?

BK: It would definitely have to be a queer-anarcho-anti-capitalist-anti-national-anti-ableist crip feminism.

V: That image in The Leaking Bodies with the pipeline and the hand emerging from the ground or the desert—it’s actually quite a direct visualization. Although this is a digital image, it is a very human realization.

BK: Yes, that’s what I mean when I say that visions of the future are descriptions of our lived realities. Sci-fi imagines what is based on the present. Sure, there are elements that are completely strange, with properties that wouldn’t be possible on Earth—planets, creatures, spaceships, and this hand casually strolling through The Leaking Bodies—that’s obviously impossible. But references like the desert, war, economy, and power, those are always things we know.

I definitely wanted The Leaking Bodies to start from a semi-realistic setting. The desert is interesting because it’s supposedly this empty place where nothing exists, no life—“Non-Life,” as Elizabeth Povinelli says in Geontologies. That concept has always provided justification for colonialism and capitalism to take whatever they want. Capitalism has settled into the desert via this life/non-life distinction.

„Crude summary: Oil as — Narrative organizer, definitely (heart of gloopy darkness). Parsani [Reza Negarestanis protagonist and fictional scientist] comes up with the idea that there is no darkness in this world, which has not its mirror image in oil. The end of the river is certainly an oil field.“

(Reza Negarestani, Cyclonopedia, S.19)

Reza Negarestani, in Cyclonopedia, writes about oil. It’s a quasi-scientific, fictional narrative about the desert, oil, and the War on Terror. Oil runs like a red thread throughout the book. Negarestani describes the desert as a cultural space. It’s a site of oil extraction, of technology, but also of war and mythology.

Drip drop.

Imagine a toxic fluid, spilling from rusty pipelines

into a dry and static desert. An animated dark,

oily liquid is leaking into a digital terrain and onto

a digital desert floor.

Imagine how it oozes and spills out,

extracted with help of machinery,

just as the hazardous goo that is crude oil.

Even an animated desert

is contaminating.

Crick crack

What you hear

is actually the surface of my animation opening.

Dripping.

Cracking

Drip drop.

Crick crack.

(Excerpt from the performance I will be as solid as you allow me to be, Getting Wet, Kunsthalle Vienna, 2021)