Maria Galindo / Version 5

María Galindo—cook, graffiti artist, and troublemaker on the streets—GLBT (fat [Gorda], lesbian, Bolivian, and recalcitrant [Terca]), bottom-oriented bastard, nymphomaniac, and member of Mujeres Creando—impostor

In institutional contexts where the expected framework is to appear as an “artist,” I introduce myself as an impostor.

In museums I am an impostor, at art biennials I am an impostor, in galleries I am an impostor, in art circles I am an impostor. It would be impossible for me to identify myself in any other way regarding the complex totality of definitions and activities that the word “art” implies in its official sense. I could not position myself differently with respect to the division of labor in any artistic institution, whatever institution that might be. I could not position myself differently regarding what the institution “art” offers its audience. I couldn’t position myself differently with regard to the relationship between artist and non-artist or between artist and artisan. This is an uncomfortable stance—even for me—since it immediately marks me as someone out of place and in intractable conflict with the “institution” (whatever that might be) and with its individual components: the museum, the curator, the gallerist, the biennial, the audience, the security personnel, art history, the white walls, the woman who cleans the hall, or the critic.

Creativity as an Instrument of Struggle and Social Change as a Creative Fact

You only see a few; behind them come millions.1

This sentence—formulated in 2000 when I first participated in an art event2—has accompanied me for over 20 years in every artistic and/or political field to which I was invited or in which I appeared as an unpleasant invader. It is a phrase with enduring power, which has helped to create a solid space for creative action, while also often leading to our being mislabeled as an “artivist” group, artistic-activist group, as an artistic collective or as dreamers who want to change the world through art and by means of art. None of these three labels fits—neither in essence nor in the reality of what we do. We are not an “artivist” group because Mujeres Creando engages in countless activities that have nothing to do with art; rather, they are about creating justice, enabling collective survival, and sustaining a conflict-ridden dialogue with—and provocation of—the society of which we are a part. We do not always operate as a collective and have never understood the relationship between the collective and the individual as a dichotomy; many colleagues simply do not care what is discussed or produced in public spheres that call themselves “artistic.” We identify and acknowledge ourselves collectively as an anarcho‑feminist movement that has developed countless working methods, some of which have occasionally been adopted by the “world of art” and perceived as artistic, even though their origin has always been political.

Regarding individual and collective work, in 2000 we decided that every work would be signed both collectively and individually by the respective compañera. Originally we only used the collective signature, but we then realized that this rendered the specific contribution of each compañera invisible. Maintaining the collective signature is a way to strengthen the movement, while also acknowledging that every production has a collective dimension—a collective subject that accompanies the reflective and working processes of all, without us necessarily being involved in everything.

We did not conceive the social struggle as stemming from art, as if art inherently possessed a transformative power; rather, what we have done—and what my personal (not necessarily collective) work has focused on—is reflecting on and creating modes of expression for provocation and struggle. We have created gusts of wind that deconstruct the schemes in which women perceive themselves and we have become experts in calibrating social perception. That is why the majority of our production over the past 20 years has been devoted to debate and the destabilization of imaginary structures. In this aspect, creativity functions as an instrument, not to produce a message, but to face the social struggle and to understand that the result of this struggle is itself a libidinal act of re-creation and re-invention of the space we occupy. Creativity is not a search for form and content; the form is the content and the content is the form. It is not about how we use color, line, curve, photograph, word, or even trash bags—it is not about “genius,” eccentricity, decoration, or rhetoric. Creativity is the skin with which we touch and explore our society, intuit its erogenous zones, its everyday sensitive areas—the zones of its pain, zones of pleasure, its negated historical memory. These sensitive zones are the only spaces in which meaning can be generated. Society as a whole is therefore a space for the creation of meaning—a meaning we have learned to sensitize, provoke, caress, comfort, and shake awake. Our own history gains greater significance when we live it as a zone of pain and transform that pain into a living memory, with the intuition of what is needed at any given moment to expose the injustices upon which the privileges of a few are built. Our intention is to disrupt social hierarchies and the spatial relationships between inside and outside, top and bottom, north and south. Provoking this disorder is our primary concern. These practices transcend the parameters of the art world’s understanding—which classifies me as a “performer” or demands that I present a work that can be framed and then exhibited as art.

This has given rise to a constant conflict that can be summed up in two recurring questions: What are you? Where are the others? We are a production collective of our own subsistence, dedicating ourselves every day to countless different endeavors. That is why each of these endeavors is signed by the person who created it and, at the same time, by the collective—which can take the form of a nurturing nest, an experimental lab, or simply a place of gathering. Some of us might be in the midst of an illegal abortion, others producing a radio program, still others researching ancient cooking recipes, while some negotiate debts with banks to achieve economic justice for fruit vendors and food sellers; some quietly brood their dreams, protected by our nest warmth; others write a book, learn to read and write, learn to dream, curse us, or flee from our shamelessness—and all of this condenses into one dynamic designation: “Mujeres Creando.” Our collective position is therefore more complex than that of an “artivist” group, and more intriguing as a social experiment. My personal position within it makes me, like each one of us, solely responsible for my own actions and my profession—which, among other things, is self‑invented and could be summed up as the unusual activity of creating forms of expression for struggle and forging new fields of perception for the endless redefinition of all questions, one after the other.

Engage with Your Whole Body

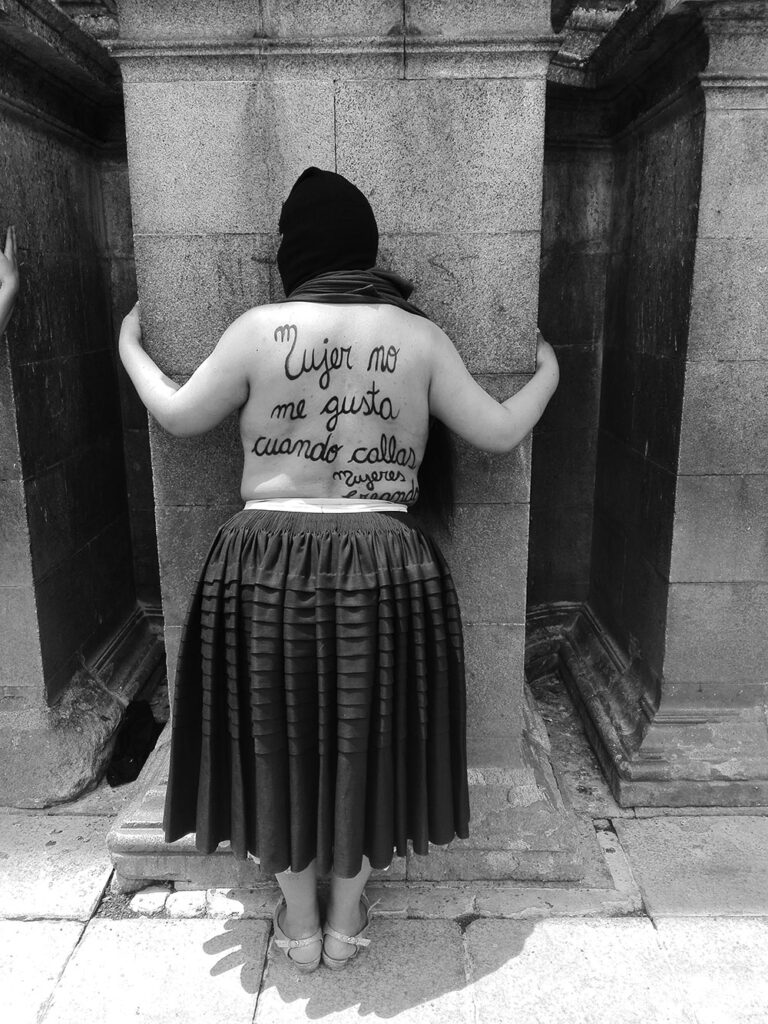

The only actions that we sign exclusively collectively, which have lasted over a period of 25 years, are the graffiti, which have established a continuous dialogue with society. During this period, we continuously applied graffiti to four cities in Bolivia. What we have written on the walls is a chained, simple, and free feminist text. This text has turned into a mirror, reflecting reality and its characters from a feminist perspective; it is the tenacity and the time that have transformed it into a mirror. It is the urgency and endurance that have given it another dimension. It is not one graffiti, it is thousands; it is not one place, it is many cities; it is not the city center, it is all imaginable places; it is not one subject, it is a series of topics. I have witnessed how girls who grew up with our graffiti allowed these sentences to influence and change their decisions.

We now know that if the walls could speak, they would demand graffiti to have mouths and arms to speak and embrace. Graffiti never loses its music, its power, its meaning; the passage of time does not wear it out; it continues to sweat on the walls, it embraces and accompanies the rebels, it continues to call for disobedience, joy of life, love, and struggle.

We are Graffiti Painters, not Blasters!

When we paint graffiti, we fight, but that doesn’t mean it’s an activity where you can’t laugh or enjoy. The verb „to fight“ has historically always been associated with a military meaning, which we despise. For us, the verb „to fight“ unites with loving, feeling, creating, and having fun. Because if this is not the case, this struggle will destroy you instead of making you grow.

Voting on what we are going to paint is very simple: I tell you my idea and read the reaction in your eyes … you like it, it fascinates you!!! No, sister, something is missing, it’s confusing—why don’t we give it this twist? Yes, now it works … how was that? It’s a game of intuitions and sensitivities. There are also graffiti that we adopt from a few beloved poets, especially from Alfonsina Storni, the Argentine; Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, the Mexican; Tecla Tofano, the Venezuelan; and Pedro Lemebel, the Chilean.3 We understand graffiti as an artistic action, and therefore we only acknowledge individual authorship when we extract a written verse, because the unstoppable force is not individuality, but the collective thinking, acting, and dreaming. We sign with Mujeres Creando, which goes beyond each one of us and also includes those women we want to call upon and seduce. We sign because we show our face for what we think, and because we want the one who reads it to know that behind the words of the graffiti, there is a concrete collective practice. However, graffiti is not a thought or a sentence written in a book; it is the sentence written on a wall—because in this act, we engage our whole body. The where and when is also the result of a collective reflection process about the space, meaning the street and the city, and the historical political space, which defines the when and why. The important thing is not to fall into the trap of proselytizing, of preaching a truth, but to sow doubt. From the walls of a small town like Oruro, or an extreme city like El Alto, our graffiti has spread to the South American feminist movement, passed from mouth to mouth, and nourished and continues to nourish feminist struggles worldwide. Graffiti already represents a cultural scene with far-reaching effects, even without our presence. The criticism against us has never ceased; we have painted on the buildings of public institutions in broad daylight and have been confronted with court cases and permanent arrests. During the first wave of the coronavirus in Bolivia, when panic spread in the country and we were under strict quarantine, the only acts of resistance were graffiti on the wall. The risks we took were enormous; we know that we gain nothing from it, in the sense that one is always in the position of the weaker party, the one who has no other means and knows that their activity doesn’t change reality. Graffiti like this is a very serious matter, an action that implies that we commit ourselves with our whole body to the historical struggle to transform our society. We do not employ a heroic body, a military one, but a vulnerable, sensitive, creative, unarmed, and non-violent body.

Art and Women: A Conceptual Trap

The connection between ethics and aesthetics does not lie in the so-called social message of a work of art, the connection between ethics and aesthetics encompasses the entire creative process;

the form, which is the content, and the content, which is the form,

the how and the when,

the what for and the why,

the with what and with what not,

and all the questions that this process answers

and all the questions it raises.

Our creative activity has a skin color, a gender, a social class, sexual freedom, and takes a position.

Your creative activity and that of those who don’t want to perceive this as well. There is no aesthetics beyond good and evil,

there is no aesthetics beyond history and social relationships.4

I firmly believe, and with all due respect, that the Guerrilla Girls were wrong when they asked, at the entrance of the largest museum in New York, about the number of women artists.5 Without a doubt, they created a historical precedent by questioning the masculinity of the art exhibited there and extending this finding to all art world institutions. Their question caused a movement for „the inclusion of women“ in exhibitions. So, where could the error lie, in a question that seemingly resulted in a historical answer? If the answer is wrong, new answers can always be found, but if the mistake is in the question, the matter becomes more complex because one has to question the concept that led you to your question. The Guerrilla Girls‘ question forces us to address the exclusion/inclusion of women. In fact, the question still echoes like a trend in every art scene and has created a drawer, the one labeled „Art by Women“ or „Art and Social Gender.“ „Women as what?“ I ask myself. „As a biological fact?—Or as a quantitative statement?—Which women fulfill this condition, and which do not?—Can the inclusion of some women be the mechanism through which others are excluded, like women with African roots, so-called Indigenous women, trans women, and non-Europeans?“

On the other hand, the „gender perspective“ has become the obligatory label for anything that cannot simply be art. Gender is confused with what comes from women or what is simply addressed to women; it is labeled as „gender“ and thereby positioned outside the central questions and debates of art. What we should first recognize is that art has a content of social gender and that we would also have a lot of pleasure in unveiling this content. But as long as the issue of social gender remains a „women’s matter,“ it is a deliberate confusion. Creating the section, the cubicle, the subtitle, the drawer „Art and Women“, just as it happens with the peoples colonially called „indigenous“, or „Art and Social Gender“ can be a politically correct approach that leaves the central debates of art within the previous territory of power, without affecting, discoloring or staining the concept of universality, which needs to be questioned.

This questioning is only possible and deep enough if it challenges all the omissions that the universal history of art itself produces. We are not only talking about exclusion but also about conceptual constructs that omit, deny, downgrade, and silence, and that create ideas, categories, and paradigms that cyclically serve power structures.

The Street as a Historical Stage: The Inside and the Outside

And I say outside, not inside,

not in the gallery,

not in the institution,

not in obedience,

not in acceptance,

not in legitimization,

not in the system.

Because you know what? The system is not everything, it’s not the entire reality, it’s not even a significant part of the reality that surrounds, envelops and unfolds us. It’s rather outside, not inside, where I find meaning and experience significance. And although it may not seem true, or it may be just the fantasy of an eternal adolescent, I dare say to you that outside the system is not the vacuum they threaten you with to intimidate you: Outside the system is not nothing.

What is outside the system of privileges. What is outside the system of administration of violence and reputations. It’s what the system from the center of its interests calls inefficient, unproductive, insane, criminal, abominable, uncomfortable, ugly, shabby and dangerous. The outside is not on the margins, it is not the marginalized of society or of history.

What is outside the system is what the system itself has not yet been able to devour and swallow up.6

The street is undoubtedly the most important place for politics and, therefore, for history. All imaginable transformative movements have emerged by collectively occupying public space; the street thus transforms into a forum from which voices are raised. It wasn’t the parliaments, the museums, nor the universities that were the sites of social change, perhaps as sidelines in some cases, but unmistakably, the street has been and is the most important forum for historical change. From Hong Kong to Washington, from Athens to Buenos Aires or Beijing—when thinking about different cities that likely have nothing in common, social protest on the street, transformative and collective, is a commonality. In our societies of the South, it is a place of subsistence, a forum for encounters and debates, and also a living space because hundreds of thousands of people spend most of their lives on the street: they nap there, they eat there, their children do their homework there. Especially for women, the street represented and represents a place of emancipation; occupying the street as one’s own space is the most important historical gesture of the last 50 years.7 It is the place where people come together, the place where ephemeral architecture and illegal market stalls are set up. The street is the outside from which no one can displace you.

It is also a space for confronting a multitude of power dynamics, starting with the dynamics of police control and discipline, but it is also the space that neoliberalism regulates and occupies with brands and large billboards of propaganda. The aesthetics of the street are complex, a play of colors, lights, and dynamics, which form part of an impossible-to-imitate scenography in its richness and complexity, especially in a society like Bolivia’s, where the street is everything. Conceptually, the street is the anti-institutional space par excellence. That’s why the architectural design of large main streets, which eliminate most of the street and turn it into a transit space for cars rather than people, deliberately erases the place of gathering. Museums and institutional spaces of art, which always lack democracy and thus chronically, time and time again, exercise their authoritarian claim, reduce their relationship with the public to the entrance fee, the motivation for people to enter the museum, to passively consume, to turn into a number, and that’s it. The tradition shaped by an anti-democratic perspective on the audience is that of the artist, who is the only one legitimized by the institution to unfold their discourse; today it is at best the curator who, with the help of the artist, unfolds his or her discourse for an audience that has to swallow it without having the right to a counterstatement. This same tradition continues in the traditional relationship of street art, which is closest to “artivism.” It starts with the missionary idea of bringing the art object to the street as a democratizing and subversive act. However, this practice closely resembles that of the evangelical preacher, who brings the good news of his sermon to the street, a phenomenon flooding the continent. Our work has never been born in a museum, a gallery, or an art school; it has emerged from social struggle, politics, and the street, and from there it has occasionally jumped over to the museum, the gallery or the art biennial. 8 The form in which we position ourselves in relation to creative action and the street is completely different. The activity we design on the street and from the street revolves around the deinstitutionalization of the artistic creative process. It revolves around opening unpredictable spaces for provocation and enthusiastic participation. It revolves around challenging all the symbolic elements that belong to this place.

Perhaps my words sound pretentious, so I must tell an anecdote that is now firmly embedded in the social memory of Bolivian society. During the filming for the series Mamá no me lo dijo9, I set one of the scenes at the Obelisk in La Paz, where we painted the penises of 12 men, who posed around a bed we had set up at the monument to the Unknown Soldier—in other words, dedicated to heroic masculinity. This staging aimed to have a compañera, a sex worker, enter the scene and compare the morality with which one judges a client to the morality with which a sex worker is judged. We only managed to paint the penises, but the action, which took place in broad daylight and without permission, triggered an avalanche of gigantic indignation all around us, the mere fact that we dared to touch the naked male body, and especially his genitals, was immediately considered an unforgivable act. A crowd gathered to voice their opinions, to prevent us from continuing, and of course, the police intervened, cordoned off the entire city center and arrested me so that the state could initiate proceedings against me as the perpetrator of the obscene acts of this scene. It’s not worth telling how I got out of this process, as it could fill a novel, but the fact is that even more than 15 years later, when I travel to any small village, I am still asked why I did it. The scene is engraved in social memory and this is just one example of how I set up the workshop for my work in social memory. The desacralization of the male body, which I wanted to reconstruct through the voice of „the whore“ in this scene, was only represented by a gesture and the reaction of the crowd immediately became part of the scene. While the crowd shouted everything imaginable, I set out to identify the archetypal characters of Bolivian society, characters who quickly emerged from the social unconscious, thus not forming a compact mass but each playing their role. I have always made the street my most challenging artistic and political arena. But for this to have meaning, the key is to install oneself in the midst of social sensitivities and thus mobilize debate, outrage, and mockery. It is not work dialoguing with the state, but with society; it is not work of demanding claims typical of “artivism.” It is work of radical disobedience, of radical search for boundaries that lead to the edges of the deepest fears. We are practically speaking a new language, incomprehensible to the state because it is not founded on violence. I do not work from a logic of reaction but from a logic of action. This means we have the responsibility to take the initiative.

Another emblematic example of this kind of action took place when, for the first time in 25 years of our work, we were invited by the Museo Nacional de Arte in La Paz to exhibit a work at a biennial. We demanded the museum’s facade—otherwise, we would have declined to participate. They agreed on the basis of the international prestige we had acquired, and we decided to intervene right at the roots of the museum. There, from the state’s perspective, the colonial baroque is upheld as the origin of Bolivian art. The most important form of expression of this catechetical art was the baroque altar. So we decided to paint a blasphemous baroque altar on the front of the museum—an altar that deconstructs the cross, the Stations of the Cross, and the Mother of God, transforming them into protagonists of a blasphemous and feminist discourse.10 The work took no longer than 24 hours; the entire intellectual community of the museum was thrown into turmoil, and once again we had inscribed a work into the social memory and debate—discussed in all media and forcing every institution to take a stand. The Catholic Church had the mural removed, and a group of nuns knelt to pray the rosary. Some may think that we are interested only in scandal, because scandals, the police, and censorship have always persecuted us—but they have never managed to silence or intimidate us.

The conditions of censorship and rejection are ones we expect as a precondition; our work is transformative, and that requires our voice to mark a turning point. We work with social sensitivities and, in doing so, provoke dismissive reactions. Without these processes, it would be impossible to reopen old wounds, spark debates, or even generate new insights.

This second anecdote serves to show how important „initiative“ is as a fundamental factor for creative action on the street. We painted the Blasphemous Altar, and society as a whole was forced to respond and take a stand. Our constant interlocutors have been groups engaged in various social struggles. This exchange enabled us to conceive our work outside closed frameworks; within these social battles, we provided methodologies and forms of expression that serve both as a mirror and a countercurrent. One of our strongest criticisms of these movements is that over the past decades they have adopted a purely reactive character—even the feminist struggle has become one of reaction: the reaction to femicides, to structural adjustment policies, to racist policies. We ended up operating and domesticating ourselves in the form of “reaction to.”

That has motivated us to understand ourselves as producers of initiative rather than mere reaction. This means that we bear the responsibility to take initiative. Taking the initiative is not easy because it requires your own horizons and dreams, not borrowed ones; it requires skill, spontaneity, and flexibility to dance a new choreography every day—different, unforeseen, and hard to digest.

The control, pursuit, and repression that the system inflicts upon us are futile and pointless because we do not delude ourselves into thinking we are stronger than it. Our response lies in our ability to position ourselves beyond its logic of power.

1 Poem 13 Hours of Rebellion, which provides the text for the eponymous song in the short film series directed by María Galindo and produced by Mujeres Creando.

2 A conference titled Utopías – Utopias, organized by Rafael Doctor—who at that time was also the curator of Espacio Uno at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía—invited us the following year to be part of the exhibition Versiones del Sur [Versions of the South], which was the largest exhibition ever held at the Reina Sofía in connection with South America. In that exhibition, we showcased a collection of street actions in which we collectively played the leading role, for which I contributed the script and editing. (www.mujerescreando.org)

3 When Pedro Lemembel visited La Paz, shortly before his fatal operation, we went from the airport to his hotel and sprayed his verses along the way—it was an unforgettable, radiant afternoon. Pedro, who watched from the car, got out to correct us whenever we forgot to dot an “i.” It was our greatest tribute to his work, and he received it as such.

4 Fragment of a text that I presented at the panel Art and Social Gender during a conference organized by the SIART Art Biennial—I can’t recall exactly when, but it must have been around the beginning of 2000, in La Paz, Bolivia.

5 Feminist artists group: www.guerrillagirls.com

6 Part of a text presented in 2000 at a conference on utopias organized by Rafael Doctor at Centro Carolina in Madrid.

7 On the Mujeres Creando website (www.mujerescreando.org) you can find an audiovisual essay dedicated to the siesta of street vendors, titled Vengarnos del Cansancio [Revenge Against Fatigue], which was created in 2004 and is part of the series Mamá no me lo dijo [Mama Didn’t Tell Me].

8 We were invited to the Venice Biennale, Documenta XIV, and twice to the São Paulo Biennial—just to name the most cosmopolitan events. We are often criticized for participating in these events, but we claim them as an international platform for our work because, in many cases (such as Documenta with Paul Preciado or the São Paulo Biennial with Pablo Lafuente), they provide spaces for dialogue that are full of respect for our work, enriching us in the debate rather than disciplining us through institutional constraints.

9 Television series filmed in 2004—you can watch some short films from it on www.mujerescreando.org.

10 Milagroso Altar Blasfemo [Miraculous Blasphemous Altar] by María Galindo, Esther Argollo, and Danitza Luna: https://www.paginasiete.bo/opinion/maria-galindo/2017/7/26/milagroso-altar-blasfemo-145987.html

A simple Google search returns more than 400,000 entries under this title, mostly concerning this work, which in turn has been inscribed into social memory and reproduced in Santiago de Chile and Quito, Ecuador.