Text / Anna Witt / Version 5

The fundamental rights are the most important rights that people in Germany have in relation to the state. At the heart of these fundamental rights is the individual. Through the regulations and restrictions aimed at curbing COVID-19, these rights were limited. Most people in Germany take these rights for granted these days —and it was only through their restriction that many became aware of them. However, there are also people who do not experience these rights as self-evident and must repeatedly assert them.

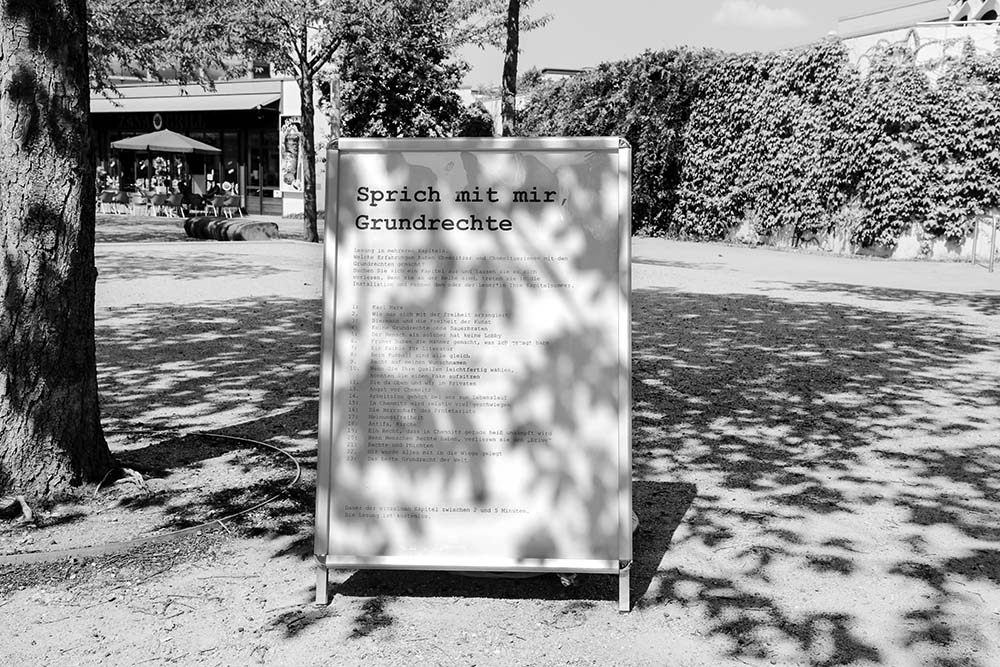

For the Sprich mit mir, Grundrechte project, Anna Witt held conversations with around 50 people from Chemnitz about their personal experiences regarding their rights. The fundamental rights were written down in the German Fundamental Law in 1949. They were created in response to the two World Wars and the immeasurable atrocities of the Nazi regime. The fundamental rights were also enshrined in the constitution of the former GDR (East Germany). Particularly older residents of Chemnitz have experienced what it’s like to live under different forms of government. Their experiences with their fundamental rights at that time, as well as their current views on their rights, are part of the project, as are the experiences of people with various socio-economic, political, and cultural backgrounds.

Located centrally, at Am Wall in downtown Chemnitz, an architectural sculpture has been installed as a meeting place for a reading performance. Over the course of the 10-week exhibition, visitors will have the opportunity to listen to passages from the collected interview transcripts read aloud by an actor or actress during fixed opening hours. The transcriptions of the conversations between the artist and the participants were anonymized, removed from their chronological order, and compiled into roughly 5-minute thematic text collages. In a private encounter with the performer in the architectural sculpture in public space, selected passages are spontaneously read aloud to visitors.

The architectural sculpture, a pavilion made of transparent acrylic glass panels, serves both a separating and connecting function. In its formal and functional design, it is reminiscent of a counter situation that is often found in official contexts and which is increasingly being used in areas of public contact, especially during the measures to contain the COVID-19 virus. (Anna Witt, excerpt from her catalogue contribution to GEGENWARTEN/PRESENCES, Kunst Stadt Chemnitz, 2020)

Exchange of ideas with the Actors moderated by Anna Witt

Anna Witt: What were your impressions?

Actor C: What struck me was… it wasn’t really the people from Chemnitz who were reached by this. At least on the weekends, at minimum 50-60% of the people came from outside Bavaria or Baden-Württemberg just for the exhibition. It was more of a tourism thing.

Actor B: I found it very interesting that despite the… there’s this stereotype about Chemnitz, that people just aren’t interested in seeing something new or participating in new things. Sure, some people walked by because maybe their minds weren’t free at the time, but there were very few people who had an outright dismissive attitude, like, „Just leave me alone, whatever you’re trying to tell me doesn’t matter to me at all.“ Well, I’ve hardly ever experienced that.

And of the people who just asked out of curiosity, like „Why are you sitting here? What are you reading? What’s this about?“ probably 70% let themselves be read to after a short explanation and a reference to the poster. I think there was a really good and maybe even surprising feedback, which I didn’t necessarily expect in Chemnitz. So, overall, I think it was well-received and positively received.

And I also had discussions with people who were at opposite ends of the political spectrum. The two most blatant experiences were a rather left-wing extremist from Leipzig and then a rather right-wing lady from Chemnitz, who is probably around a lot in the city. They were there independently of each other. But I thought it was good that I was able to have a good discussion with both of them after the reading. Nobody raised their voice or became aggressive or insulting. With the more left-leaning person, I found it quite astonishing—almost a bit intimidating—that he spoke so coldly about how he would deal with right-wing extremists. I found that a bit upsetting because he was of the opinion that the end justifies the means and that violence should definitely be used. That’s not my opinion.

Anna Witt: Did the discussions happen as a response to what was read aloud?

Actor B: Yes, definitely. Of course, a lot of it was about right and left. For example, Antifa, Kirche was read relatively often. And there are also a few sections where it is relatively obvious that the arguments are coming from a more right-wing perspective. But that was definitely discussed with a lot of enthusiasm.

And then the lady from the city, she was very passionate, very eager to communicate with me. I didn’t necessarily expect that, because many typical AfD voters tend to say things like: „Leave me alone with your crap. We don’t want to know any of this because you can’t change our minds anyway.“ But she asked questions and was open to conversation. That was a good start for finding common ground and creating space for things that otherwise might not be so easy to discuss.

Anna Witt: There’s this polarization in Chemnitz. Was that noticeable in the reactions?

Actor B: Yes, to some extent. Of course, since the chapters are from different people and mixed together, at first it was a bit confusing, and the transitions weren’t always so clear. Well, I’ve also been asked a few times why this isn’t presented by several speakers so that it’s clearer.

Actor C: I think that, precisely because there were different opinions in the individual chapters, a discourse was created. This made it quite objective and people always found themselves in some part of the text. It was relatively easy for people to open up and express their own opinions. That’s how I felt about it.

Anna Witt: And how was it for you, that you were repeatedly in situations where you had to discuss things with people? Was it exhausting or interesting?

Actor A: There was one moment where it was really… it was about the church. The man was a priest, and the woman was also on some Christian trip. It was really lovely… In the end, they were preaching in that glass booth. The man really got into it, praising life, raising his arms to the sky, it was truly beautiful. This created magical moments. By looking at what was not possible at the time.

Sometimes it was personally difficult for me too. For example, refugees – I had three – two from Syria and one from Africa. And they all shared their stories. Every time, the topic came up of how difficult things were for them. They want to work, do something, but they couldn’t get housing. Everything that occurs in the text. Or an LGBT person who has experienced this him or herself and undergone therapy. And I felt that every time we came across these injustices, where fundamental rights were being violated, people really opened up and showed themselves. In those moments, I wished for a bigger platform for what we read out, what we somehow abstractly present, what we deal with.

When these people came and said, „Yes, I know that. I’ve experienced that. Yes, that too, and that too.“ To see how systemic it is… that things don’t work out the way you would hope. Based on fundamental rights. That was really fascinating. I hadn’t come across that before with this topic.

Anna Witt: Did you feel the same way? How was it for you?

Actor C: I had some people who shared a lot about their past and recognized themselves in it. But on the other hand, because the people in the text remain anonymous, their biographies aren’t clear, some people said: „Well, I can somewhat relate, but for me, it was completely different.“ They always added how it was from their perspective. And I found that very interesting.

Anna Witt: And were these mostly older people? How was it with younger ones?

Actor C: I had one person who I think was from Brazil. A student. He came twice and listened to it, to learn German. He was trying to understand the content of what was being read at the same time. He’s only been in Chemnitz for a year, so not long, and he said that he didn’t see the city as being as right-wing as the media portrays it. He actually felt comfortable here, which was nice to hear.

Actor B: I can actually confirm that. I also met someone from Turkey, and he’d only been in Chemnitz for three weeks. He’d lived in Frankfurt before. In any case, he’s been learning German for a few months now. He was there with his carer, a local from Chemnitz who helps him with German. They asked if there was anything in English. I first read the script in German, then translated it section by section into English to make it easier for him to understand. He was really happy about that, and I asked him how he felt about being here, if he felt welcome. He said he liked Chemnitz very much and had hardly had any negative experiences. Which was really nice to hear. Many locals say: „Yeah, all those right-wing people gathering here.“ And then to hear that there are people who don’t experience it so terribly is really nice.

Anna Witt: The text often touches on this left-right issue. But not only that. Do you think that if you live in Chemnitz, you also sometimes just get fed up and are happy to talk about other topics?

Actor A: The GDR was actually still more present, especially with older people, who had a lot of need to talk or discuss. And I couldn’t really contribute to that myself…

Actor B: Many people shared with me how they experienced it. And since I didn’t live through it, it was good to hear personal accounts, apart from what we learned in school.

Anna Witt: I actually expected that when I talked to people about their experiences in the former GDR, that topic would be over. But in reality, I sometimes had the feeling that there was still a big need to talk about it. When I spoke with the OMAS GEGEN RECHTS (GRANNIES AGAINST THE RIGHT) in Chemnitz, I almost had the feeling that they had never talked about it before. How did you experience it?

Actor C: There are definitely some in the age group who lived through their youth and maybe even beyond in the GDR. And I don’t think they’ve really come to terms with it yet. At least in the discussions, it felt like some people were remembering, but maybe they had suppressed that time… certainly, some things came up. There’s this one part where the woman spoke about the family image back then. And there was actually a young man who said, „Yeah, that was the case in my home too.“ So, I don’t know whether some things are perhaps being reprocessed or have not yet been processed at all.

Anna Witt: Did you have any bad experiences? Moments when you thought, „Oh, shit! When will this project finally be over?“

Actor C: At that time, there was the mayoral election… on one day, the AfD stand was directly opposite. And of course, those people… more from that side. They looked over briefly and made negative comments. That was one of those days. Even though people still came, that was the moment when I thought, „Oh, now…!“ I hadn’t read to anyone in 45 minutes, but I’d heard five people talking about how taxpayers’ money was being wasted and that something like this didn’t belong in Chemnitz.

Actor B: I didn’t have any bad experiences with people. Yes, there just weren’t that many people there that weekend. That was a bit of a shame. I think refugees are a complex topic in the city because some behave in a questionable manner. At one point, I had a group of seven men standing around me… It’s complicated, because as a woman, you’re either not taken seriously or are taken too seriously. In the sense of, „They walk past you and look at you like you’re a piece of meat.“ But I did have very good conversations, for example, with a refugee from Turkmenistan. He’s doing an apprenticeship in Chemnitz, has been here for a few years, and talked to me about why there are so many prejudices and fears when it comes to refugees. There’s this general, misguided anger, more or less on both sides. And I think it was really good to talk about this with someone who is directly affected. I think it helped both of us understand and contextualize these uncomfortable situations better, and to see that things can also be different.

Actor D: I have to say, it was very interesting for me because we’re a bit generationally apart. But I can only really speak of positive experiences. Whether foreigners or locals… although I had the impression that, as is so often the case, it was more honored and better perceived outside of Chemnitz than by the locals themselves, who probably had more … almost had a need to talk rather than a need for information. That’s kind of the trend in Chemnitz.

Anna Witt: What overall feeling did you have about how this public art project in Chemnitz was received?

Actor D: Very good, with all the stumbling blocks that we are used to in Chemnitz. That’s exactly what Chemnitz needs. And the perception is correct, that the outside perspective, from people from Leipzig or Frankfurt, on the city is often more positive than from the locals themselves. But I think that’s the way to turn it around. And projects like this offer that opportunity and these approaches.

Actor B: I think a lot of positive feedback came from people who either moved here or haven’t lived their whole lives in Chemnitz. Most of those who came to see the entire exhibition came from Leipzig, Dresden or other cities. They usually had the flyer and read everything on it. There were definitely a lot of interested people, but I think fewer locals.

Antifa, Church

Yes, when you call something anti-fascist around here, especially among older people, the association with the GDR is obvious. It was a state doctrine there. But I think this state-run anti-fascism has a very different kind of after-effect. Namely, that there wasn’t really any anti-fascism during the GDR era. Fascism was externalized by exporting it to West Germany and saying, “We don’t have to deal with that.” The churches here are marginalized minorities. The former GDR is the most atheistic country in the world. But what I wanted to get to – the structures are missing. Ultimately, what’s lacking here is civil society.

Someone once asked me why I actually like soccer and why I like this club, and I always compared it to church. Well, I don’t go to church myself, but it’s still something that was instilled in me, something that has always been there somehow and that I would do almost anything for and that also determines my life.

On the 2nd of September, Chemnitz is playing against Babelsberg, and Babelsberg is obviously left-wing and does certain things with Antifa, and we get labelled as the right-wing ones, which might concern 200 out of 5000 people, but whether they’re really right-wing, who knows. These are just the kind of jibes that could happen with banners.

There are just a few clubs that are left-wing, like Babelsberg or TB Berlin. But as for right-wing clubs, to turn it around, they don’t exist. There are always clubs that get labelled as such, like Chemnitz, Cottbus.

There was the incident in Chemnitz on March 9th last year, you know? Where a memorial was held at the stadium for a fan who had a past that clearly ties into the far-right scene. They held a memorial in the stadium for a fan – for a person – and because of his past, the media spun it like: „He was a Nazi, and everyone who was silent for that minute is a Nazi too.“

It always comes down to right or left. Sure, I can say something as a teenager. Maybe he once uttered a right-wing slogan, but that doesn’t mean he’s a bad person just because he repeats something. Maybe he had a bad experience or whatever. And the far-left… well, I find them even scarier, because they used to be very dark red here. And they’ve often been willing to step over dead bodies. A young person, if they’re really interested, first needs to engage with these issues. And they should have the right to hold an opinion that’s not just conformist.

Humans as Reproductive Beings

Humans are designed for intergenerationality; they are reproductive beings at their core, which is somehow deep down inside, and in this respect human beings are never isolated and alone, and I don’t read that in the fundamental rights either, and I actually see it in such a way that the fundamental rights make it clear that there are also limits, limits in how we interact with each other on the one hand, and on the other hand I also see what is implicitly mentioned again and again, despite all the freedom of the individual, the responsibility for the big picture.

So naming fundamental rights is fine, but the question is, how can I make use of these fundamental rights? This is something we often lose sight of. Precisely because we don’t focus on the groups that are affected. Because we only ever perceive them as a mass, but not as individuals. And every individual has their rights.

These rights have been assigned to them and granted to them by people; they do not come from God, they come from us. We are responsible for these rights. We have named them and we are also responsible. That is perhaps the point at which we could start. We are responsible for bringing these rights to life.

For example, everyday racism. That puts us in a position of responsibility, namely to prevent a bus driver from refusing to take someone because she is wearing a headscarf. That means I start discussing the issue with the bus driver until he throws me off in an extreme case. I don’t care about that. That’s my duty as a citizen.

Now we’re back to rights and duties. They have the right to be here, but they also have the duty to integrate, right? That’s how I see it. They have to follow the rules here. We’re a state that wants to integrate people. But anyone who wants to be integrated needs to do something for it.

As I said, I even find it a bit rude when people speak in a foreign language I don’t understand while I’m around. It’s not okay.

It’s taken for granted that I’m respected here, that my rights are the same as everyone else’s, but in practice there are many things that are simply not given to you – so I’ll say – at 16, I had the right to have a normal carer here in Germany because I was a working child in Iran. My hands were too strong and the court took that as a reason to put me in a home where I had to live with adults, they didn’t take my basic rights into consideration.

I was supposed to get my rights here, but I didn’t get my rights, I didn’t have the chance to go to a good school at the beginning, to learn better for a few years, to be able to prove myself, to learn the language, to be able to integrate well, which is meaningless to me to this day.

After six years, I got my residency permit. Six years! If society expects me to integrate, to become part of it, I want certainty, an answer after a year. How safe I feel here depends very much on the fact that I can develop, that’s how the effects are, and not just getting an answer after 6 years.

The world’s best fundamental right

Now, I’ve spent a lot of time studying the GDR’s constitution, and the more I’ve learned, the more I appreciate the Fundamental Law, especially Article 1!

You can truly say this is the best Fundamental Law in the world – I don’t know others, but that human dignity is enshrined as Article 1, that’s very specific due to German history. With Corona… I found it very interesting in light of the global pandemic, because I come from the healthcare sector, I know what it means… Protecting fundamental rights is good, but I am very ambivalent about it. It’s good that citizens have pointed this out, but it doesn’t need to be as aggressive as it is today.

Germany really praises itself – we have the best Fundamental Law in the world, everyone is equal before the law – but if you look behind the scenes, many people suffer. I know people who have lived here for 14 years without any certainty about what will happen tomorrow…

These people must have a reason for staying here, otherwise, they wouldn’t. And I think they just accept it and get by. Then they’re forgotten by the city. I read in a book that in Germany, you have a right to asylum, that you won’t be imprisoned! We have over 600 or how many, I don’t know, deportation detention centers here in Germany, where people are held so that they can be sent back. We have that here, we have that in Dresden, in other federal states. I don’t understand that either – I’m not against it at all – but many don’t even debate about not understanding or misinterpreting fundamental rights. The majority of people haven’t had their rights in the last 4-5 years – that’s why I think Germany is celebrating itself and its fundamental rights without understanding how many people have been cast aside.

We all take these fundamental rights for granted every day, unconsciously. However, as soon as the state tries to interfere with fundamental rights, which we all think are great, but which we may not even be able to name. But as soon as the state interferes, you realize and you really feel these rights. They’re constitutionally guaranteed, and that’s something really great. I find the discussion about health vs. human dignity fascinating – not to play them against each other, but to weigh them. That’s a very interesting conversation.

The dignity of a human being – it has come up again, especially after Wolfgang Schäuble’s remarks, not sure if you heard, but it was really about whether we should take harsh measures to prevent people from dying. But dying with dignity also involves a dignified death.

At any cost, but we’re talking about human dignity, which is untouchable, not about death, even though we all have to die. And this, of course, has caused a lot of irritation and protests, even in the churches… But I think it’s an aspect worth thinking about, that you ask yourself: „What do we actually mean by that?“

I do think sometimes, that I’m actually grateful to have lived through the late phase of the GDR as a child because it gives me a direct comparison. I also had an interesting family history because my grandfather worked for the Stasi, and we had a lot of conflict in the family. I also saw how human interaction was possible despite very different political views – maybe not in the hottest conflicts, but in an interaction that’s shaped by reconciliation, by finding each other again, beyond political opinions or thoughts.

Karl Marx

What do you actually think about fundamental rights? You can see it clearly here in Chemnitz, at Nischel, how fundamental rights can clash. This is where it all boiled over. What’s interesting is how this memorial is so polarizing that this street has become a kind of regular parade for both left and right. You always have young people sitting here from all kinds of countries, which of course doesn’t suit the people here. For example, the AfD’s mayoral candidate called it „Little Arabia“ and then in the same sentence said: „They’re taking our customers away from the traders.“ That shows the question of how public space is used. What does that have to do with fundamental rights? Here, anyone can do whatever they want. It doesn’t bother me that those two over there are eating their McDonalds bag in front of the McDonalds. I couldn’t care less where they come from.

I can also say to a few guys approaching me trying to rob me: „You can’t do that!“ That’s in the basic law. Property rights. The social responsibility of property, which is also in the basic law – right behind it, but no one remembers that. Property comes with responsibility. You’re not just allowed to hoard money; you have to do something meaningful with it. That’s something we could almost use to argue that people should think carefully about what they do with their wealth.

We’ve been catapulted back to the time of Karl Marx, if you like. So capitalism unbridled. And that has a lot to do with digitalization and, of course, with the changing world of work. Who do I have to tell? You know better than I do. It’s a model of neoliberalism. It’s self-exploitation, which it demands from you. And of course this also reduces the understanding of what democracy is actually for. What do I get out of democracy? I go and vote. And then that’s it.

I only became involved with Marx after reunification. And what’s that one quote attributed to Marx? „Freedom is the insight into necessity.“ It’s a good quote because it’s like with traffic rules. I can use my freedom, but I still have to follow general rules. And that again requires educated people.

How can you feel free? There is no person who is truly free. You always have some kind of duty. I would feel free if I were somewhere – doesn’t have to be Berlin – where I have peace, where people are cool and don’t call you a fag or a tranny. Freedom has many different definitions.

In the past, men did what I said.

I think you also have to consider the worldview of the founding fathers and mothers (there weren’t many) and that was of course one that was very strongly influenced by Christianity. Some things are simply better understood from that time, in every respect, i.e. of course with the experiences of the Third Reich, but also with traditional, very conservative values.

You can also see that these are basically goals that are described there – equality between men and women – I mean, you have to think about the fact that the fundamental law came into force and then for decades it was the case that a woman needed her husband’s consent if she wanted to pursue her profession.

That men and women were equal in the West wasn’t just the case. That had to be fought for all the time. I have to say, it was different in the GDR. For example, I earned more than my husband. He worked on construction, and I worked three shifts in the textile industry in the GDR. I did correspondence courses on the side and became a textile engineer. There was never any question: „Who does what?“ The men did what I told them, just like the women. So there was one pay grade and that’s what I got. And now we have to fight for that again. The clock is being turned back. That’s why I got involved in the union, because I said, „We’ve already had this.“

The right to equal treatment. Today, we have a mood of „Women back in the kitchen!“, more or less. Before and especially with the lockdown. Especially the mothers who are supposed to work under certain circumstances … they have to educate the children. And they still have to provide for the family, like food. For me, it was self-evident. I grew up like that. I was born in ’52, in Chemnitz. Then it became Karl-Marx-Stadt. And now I live back in Chemnitz. And it’s like this… boys and girls: equal.

Exactly. But I once learned this from a young feminist. She said: „Yeah, these high women’s rights in socialism in Czechoslovakia…“ with a really progressive abortion law, actually very far ahead, and she said, „We didn’t work for that. It was just there.” So, it wasn’t discussed. Maybe not internalized. It just „plops“ there.

There wasn’t much room to create something new, something of our own. Now, for the first time, there’s space to bring reports that things weren’t all bad in education back then. And I think we should actually be proud of what we had in the past. It’s not something we can take for granted. What we can do today, what we’re allowed to do today. We have to stand for it every day, be vigilant, and the civil rights activists from ’89 – they deserve the greatest recognition. I don’t understand why we’re not proud of that revolution – why we don’t simply celebrate this anniversary with our heads held high. I think we should celebrate it more, as a community project, East and West.

Fear of Chemnitz

But freedom of speech also protects the person opposite me. Namely, before I impose my opinion on the other person. Most of the people you talk to, and I talk to, have never been in the GDR. They’re of an age where they grew up in the West, in the democratic system. But they haven’t internalized it yet.

And it’s quite exciting that younger people in particular are suddenly starting to conjure up this feeling of being oppressed again. You could almost say it’s all about affects, feelings, emotions. Fear is nothing else.

I don’t know what you’ve heard about Chemnitz. A lot of people who come here for the first time tell me they’re afraid of Chemnitz. Chemnitz has a very bad reputation. It is certainly not without good reason. But I’m not one of those people who say Chemnitz is treated too harshly. But Chemnitz isn’t just all bad. If you look closely, you can’t feel threatened here.

But Chemnitz is of course a mined area. You can be drawn into lines of conflict relatively quickly that you don’t actually want to be involved in. Sometimes it’s enough to be associated with one side or the other. A high degree of polarization. I rather believe that this is the last gasp of the fascists, to use Matthias Krenn’s words.

So you’re not afraid of being attacked? Well. I guess… I have a friend. He was attacked because he’s not German, has a different nationality, and is bisexual. It’s sad to see that there are people on this planet who are against religion, skin color, sexuality, against identity. It’s just sad that people have developed like that.

But I’m not religious. I was baptized, but I’m not religious. The Bible says, many say, that God is against gays. But that’s not true. The Bible says that God accepts everyone for who they are. A lot of Christians misunderstand this. My family is relatively religious. My grandfather is Christian. He had to come to terms with the fact that I have a new identity. It was difficult for him, because… I’m still his granddaughter. But now he’s managing. But I also know Christians who are gay.