Interview / Linda Klösel, Yvan Sagnet / The new gospel

( a film by Milo Rau ) / Version 5

As if – Christ Stopped at Eboli

The Turin doctor, painter, and writer Carlo Levi commemorated the suffering of the people in Basilicata in 1945 with his eponymous documentary novel. The Italian fascists had exiled him to Aliano, near Matera. The provincial capital Matera was considered a „national disgrace“ because of its poverty and backwardness, with people—many landless farmers—living in the Sassi, the old cave dwellings, under conditions of unimaginable misery well into the 20th century. People have lived in Matera for nearly 12,000 years, making it one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world. Matera is as ancient as Jericho or Aleppo.

Perhaps because of this – the nested houses, the grottoes carved into the tufa, narrow alleyways, steep steps and the surrounding hills all suggest a nearly biblical scene – Christ – Man Enrique Irazoqui (Per Paolo Pasolini, 1964), Christ – Man James Caviezel (Mel Gibson, 2004) and Christ – Man Yvan Sagnet (Milo Rau, 2020) came to Matera after all.

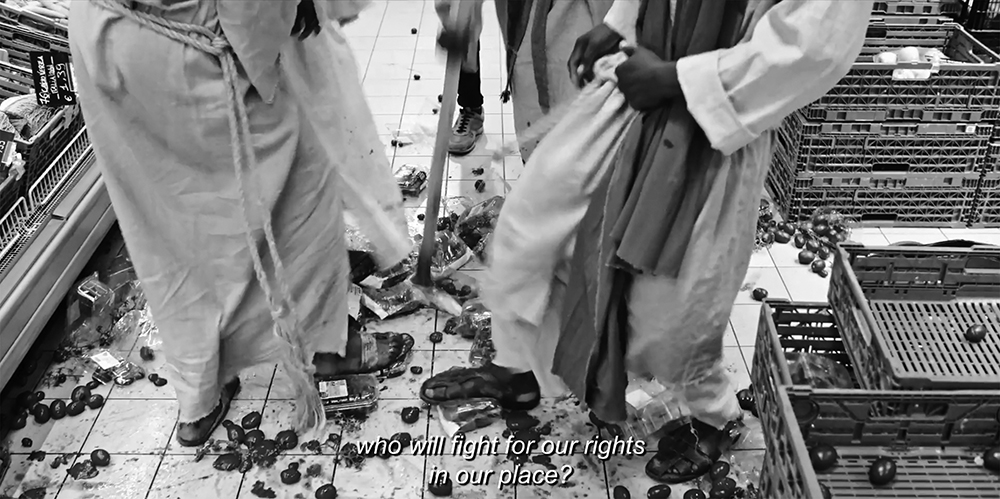

Milo Rau’s The New Gospel is a highly political blend of reenactment and documentary, where the Passion narrative of the Gospels intertwines closely with the political actions of Yvan Sagnet and his fellow activists. For the first time, a Black Jesus appears on screen, representing those who suffer the most under the exploitation of a capitalist global order—people who, due to the Dublin Regulation, are trapped with nowhere to go, criminalized by the current Italian government, and exploited by the Mafia and farmers under the pressure of large food corporations and supermarkets on the plantations.

With Milo Rau, the art of representation has come to an end. The intensity of preparation, the work with actors—both amateurs and professionals—and the blending of reality with representation, fact with fiction, lead us eye-to-eye with the “existential reality of life.” Filming locations are also public stages, where a demonstration against the eviction of a workers‘ camp becomes a procession to Jerusalem, led by Jesus in historical costume and flanked by cultural tourists with their phones and sunglasses. Costume fittings and castings are part of the film, at the same time also a kind of milieu study where non-professional actors discuss their motivations. Jesus discusses with his disciples, seated on the white plastic chairs we all recognize from vacations, the situation of „illegal“ migrants in Italy. It’s often unclear whether a film is being made or a political struggle is being organized, but these debates are also integrated into the setting. Has the priest with his homage to Christ – Man Sagnet – fallen out of time, or the audience witnessing the torture?

Milo Rau portrays Jesus as a social revolutionary and tailors this role closely to his lead actor, because: “I have not come to break the law, but to fulfill it, so follow me.” The motif of the fisher of men runs throughout the film, but do we still need this charismatic, sanctified Redeemer today? What about all those, throughout history and even today, who are imprisoned, tortured, and murdered for their convictions, political resistance, and fight for the oppressed? The person of Sagnet, who rebels against the established power structures out of conviction, personal experience, and a desire for justice, is partially overwritten by the person of Jesus, who believes himself to be in possession of all-encompassing truth because he is sent by God. Throughout the millennia, the construct of Jesus was theologically exaggerated and glorified due to this circumstance that he attributed to himself, which ultimately led to the most egregious atrocities being committed in his name and the establishment of a world order that still thrives on post-colonial structures and exploitative relationships today. “When two or three are gathered in my name, I will be among them.” Who would doubt the words of a son of God, or even discuss them at eye level?

And especially today, in a time of massive uncertainty and disorientation, offering a savior figure with the „right“ messages as a response and projection screen seems problematic. Today, as then, there are quite a few „fishers of men“ with promises of salvation of all kinds and on all sides. A warning against manipulation and a call for critical reflection are, of course, essential. e glorification of a single leading figure, icon or martyr, always exposes itself at some point. Even the social revolutionary Che Guevara, quoted in the film and on the protesters‘ posters, who has been a myth and cult figure for decades in left-wing liberation movements, reveals himself today in historical analysis as an unrelenting doctrinaire with apocalyptic fantasies of destruction.

Even if we’d like to anticipate Jesus’ fundamental messages, this figure is just too burdened. Over the millennia, he has been misused to cement power structures, establish a crushing concept of guilt and atonement, and declare suffering—especially for women—as a constant from which only the Redeemer can free us. In this context, both inner and outer resistance must be allowed.

I would have preferred if Milo Rau’s Jesus were not like the one we have internalized through all these films. I would have liked him to be more imperfect, angrier, more lustful, less patient, perhaps arrogant—just simply not so holy. Milo Rau shows us his historical Jesus as we know him—one friend described him as „pathetic.“ And he finds powerful images, always underscored by Mozart’s Maurerische Trauermusik, painfully beautiful, they lead us to the elementary questions of our abysses and contradictions. One can’t completely escape it, and that is probably his intention.

Nevertheless, this film is a campaign film for an essential project: The Revolt of Dignity. In the first paragraph of their manifesto, it says: “The European idea is facing its end. A politics of fear, exclusion, and exploitation has replaced the principles of freedom, equality, and human dignity to which the European Union unconditionally committed itself in its founding treaty.” Sagnet, Rau, and their team, together with 30 other organizations, NGOs, and activists, have created a broad alliance against the xenophobic policies of the Italian government. For the first time, small Italian farmers and migrants are fighting side by side for their rights against the large food corporations—a dangerous endeavor, as these corporations cooperate with the Italian Mafia. Parallel to the filming, The Revolt of Dignity led to the creation of The Houses of Dignity.“ In the end, 1,350 homeless refugees and migrants, including some actors from The New Gospel, are to have permanent homes and papers. A small farm near Matera now grows vegetables completely free of exploitation and pesticides.

Milo Rau is one of the sharpest critics of the global economic policies responsible for crises and misery. With his documentary-infused „real theater“ (a term coined by Alexander Kluge), he advocates for understanding artistic production as a solidarity act. The goal is to support civil self-empowerment in the fight against brutal exploitative capitalism and to create living and action spaces that are not provided by global economic capitalism.

The environment, democracy, and human rights are sacrificed to the profit interests of multinational corporations. And we are all part of this perfidious system that entangles us in dependencies that we need to be aware of, especially if we are not yet existentially at the end of the exploitation chain. The strategies of global corporations invest in our contradictory needs, which they have ultimately created, only to walk away with the maximum profit. After all, don’t those same corporations, responsible for the exploitation of raw materials and labor elsewhere, also invest in research, sustainability, and even critical art? What do we really know about the actual production conditions of, for example, organic food and textiles? Even though we are happy to pay for the comfort of a clear conscience. It’s about looking more closely. We largely accept that a few live off the backs of many and destroy our life resources. We should stand in solidarity against power concentration and manipulation, expose their machinations, and hold politics accountable to break up economic monopolies and give room to a system of self-organization and personal responsibility.

Version: Can you tell our readers how you, as a student from Turin, ended up working in the tomato fields of southern Italy and what situation you found there?

Yvan Sagnet: I came to Italy in 2008, enrolled at the Polytechnic University in Turin, and graduated in 2013 with a degree in engineering and telecommunications. But at the same time, in 2011, I went to southern Italy to harvest tomatoes to finance my university studies. What I found there was a system of exploitation of seasonal workers, especially migrants, a system called “caporalato”— a system of illegal recruitment of workers. I never expected to find something like this in Europe. I worked fourteen hours a day, earning an average of two euros per hour, drinking dirty water, sleeping on filthy mattresses, and showering every two days. People weren’t treated like workers, but like slaves. I experienced this firsthand, and it drove me to rebel against this system. I encouraged my fellow workers to revolt and strike because this is not a working system that respects people; it’s a system of slavery. We were lucky that our strike garnered attention on a national and international level because at that time, the exploitation of seasonal workers wasn’t really on people’s radar. As for legislation, we were successful with the law against the caporali. I decided to dedicate my life to the fight for social justice, to the fight for the respect of rights. I’ve been fighting now for ten years.

Version: You’re talking about exploitation, or worse, slavery. By now, we can also see all over Europe, especially through COVID-19, that workers are being exploited everywhere. In Italy, it’s worse because there are so many refugees who have no papers, no access to healthcare, housing, and all of that. So how can they claim their rights in court without running the risk of being deported themselves?

Yvan Sagnet: As you said, the problem of exploitation is a European issue, not just an Italian one—it’s an international problem. These migrants are fragile subjects because they have no rights and often no choice, which makes their exploitation by companies easier. As for your question about how they can get out of this situation, I think that people of good will need to take care of this.

Italian and European institutions should finally focus on the issue of exploitation, on the problem of slavery in Europe. When I speak of people of good will, I mean all those who care about human and social justice. We should promote a culture of work, a trade union culture, we should support struggles. There should be many rebellious migrants, a large movement of all European workers. What’s crucial is global support for workers‘ rights against the neoliberal capitalist exploitation system. We also hope that the European Commission, as well as European and Italian institutions, will introduce stricter laws against these exploiters.

Version: Who are the caporali?

Yvan Sagnet: The caporali are essentially intermediaries, people who were farm workers in the past. They’ve moved up the ranks a bit and help Italian farmers who don’t speak French, English, or dialects to get workers for their fields. The caporali abuse their position as intermediaries because they make the workers work on their own terms. They determine the wages and working hours. The mafia uses these caporali to further increase their profits.

Version: With the Nardò uprising in 2011, you managed to push through a law against the caporali. What does this law entail, and what has its impact been today, nine years later? Who enforces this law, and what options do workers have to defend themselves in court?

Yvan Sagnet: Before our strike, there was no law against the caporali. Today, it criminalizes this type of labor brokerage with a penalty of five to six years in prison if someone is arrested. But the law says something else that is very important, namely that Italian farmers are also held accountable, because they hire the caporali and that is also punishable. If the caporale is arrested, the farmer gets arrested as well. It’s a law that indeed punishes anyone who directly or indirectly supports the caporalato. It also allows for the confiscation of property, cars, fields, and businesses. Thanks to this law, there are many investigations against the exploitation of workers across Italy. That’s a huge step forward, but with this law alone, we can’t stop exploitation in Italy. There’s another “caporalato” we haven’t even discussed—the “caporalato” of the economy, of the capitalist system, driven by multinational companies and supermarkets.

Version: The pressure in production chains on the most vulnerable is increasing, and basically, every level of the chain pushes that pressure downward.

Yvan Sagnet: If you only tackle the level of the caporali and farmers, it won’t work. The first level is the big supermarket chains because they are the ones who set the prices of products. Under their pressure and that of the trading chains, farmers are forced to exploit their workers. We need to change the economic production model. That’s why I founded my NGO noCap, which certifies products harvested by workers who have proper labor contracts with farmers and whose product prices are realistic. Additionally, through noCap, we’ve created a network of conscious farmers and supermarkets. We want these products to reach as many consumers as possible throughout Europe because it’s their purchasing power that can make the difference. If we go into a supermarket and buy products without questioning where they come from or how they were produced, then we ordinary citizens will unconsciously give our money to the caporali and the mafia, as we are doing at the moment. So we need to consume consciously and responsibly so that our money ends up in a legal economic cycle. That’s really the key.

Version: I also think it’s important to raise awareness among consumers, but what can be done on a political level, since these companies have strong lobbies? How can political pressure be applied to these companies?

Yvan Sagnet: We have many proposals that we are putting forward at both the European and national levels to ensure price traceability. For example, at the European level, there’s the CAP, the Common Agricultural Policy, which is a European support program for farmers that invests billions of euros into European agriculture. noCap is advocating at the European Union level to ensure that this money only goes to farmers who respect workers‘ rights. There must be a minimum wage at European level, because if it only exists in Italy but not in Spain or Greece, the problem will only shift. In addition to the minimum wage, there should be strict controls to ensure that it is enforced. There are a number of measures the European Union could take to make our production model fair. The European Union spends 60 billion euros every year across European countries, but where should that money go? To the mafia, into the pockets of multinational companies? It must go to the farmers who comply with the law.

Version: I think the problem is even bigger and more complex. If, for example, wheat subsidized by the EU through agricultural subsidies is exported to Senegal, the result is that it is offered there at prices that do not even cover the already extremely low production costs there, destroying the economy and livelihoods. The EU is responsible for that.

Yvan Sagnet: That’s a good question because it’s the global market economy system that causes distortions at the international level. The EU’s subsidy policy leads to unfair competition, especially for poorer countries. But there’s also the reverse problem, such as oranges from Morocco or tomatoes from China, which undercut prices here in Europe. I think we can only solve this problem through a broad international movement or a system, a revolution that starts from the cultural consciousness of the people. The most effective way to combat the liberal capitalist system, which is based only on the product, on consumption, buying, trade, and money—while disregarding people and their rights—is critical mass, critical consumption. If our traceability and education system works, the big multinational companies won’t stand a chance because people want an egalitarian, sustainable economy.

Version: Now, I’d like to talk about the film with Milo Rau, The New Gospel. What was it like working with him since you’re not a professional actor? How did you develop the role of Jesus?

Yvan Sagnet: Milo Rau was looking for an actor who is an activist and a fighter, someone who fights for the law. Jesus also fought for the poor, for justice, he was indeed an activist, a trade unionist. Milo Rau saw that figure in me. He said, “Yvan, because of your past, because of the strikes, you’ll be my Jesus.” He wasn’t looking for a professional; he wanted someone who could convey the message. He helped me throughout the entire filming process to deliver this message and also to learn some professional acting scenes. Jesus also fought for the poor, not the rich, he cared for the immigrants, for those who have nothing to eat and he cared for the farmers. Jesus today would be with those people, and he’d be focused on these issues.

Version: Was it easy for you to find the role, to play it?

Yvan Sagnet: Besides the fact that I’m very religious—my culture is like that, Jesus is a person I deeply respect—it was easy for me because I discovered that Jesus was also a trade unionist, that he destroyed churches, fought against the powerful, and spoke to the people. Essentially, that’s what I do every day—I speak to workers, to the people.

Version: I have my issues with the figure of Jesus. Do we really need this charismatic leader, a savior who can’t be questioned and whom people worship?

Yvan Sagnet: I understand that very well, but Jesus also said, “Don’t look at me, look at what you do.” He had twelve disciples and they went out into the world to talk about problems and the gospel. The concept of Christ is not the person of Jesus, but the message. When he died, he left behind twelve disciples, who became twenty, a hundred, a million. He said, “Go into all the world, defend, speak, spread the good news.” The good news is to love your neighbor and not do harm, but the good news is also helping the poor, helping those in trouble, redistributing wealth, not exploiting. That’s what we need to do today. The role of the film is to create a large movement of many people and raise awareness that the problem is multinational corporations, and that everyone can be part of this revolution. It’s that part of Christ that we need to look at.

Version: Maybe the story was actually very different. Maybe he was an equal part of a group of rebels and only through his execution did he become a martyr—something the Catholic Church used to establish today’s world order and power distribution in Christ’s name.

Yvan Sagnet: Yes, there’s an interpretational issue, and the Catholic Church has interpreted this history in a centralized way, whereas it should be seen in a decentralized way. The church is you, it’s me, it’s all of us. Today’s Christians have lost sight of Jesus’ message. When I see Salvini or Trump going to mass with a rosary, it means nothing. They should be taking in the poor, refugees, and migrants, and taking care of them. We should all do that. That’s the message. Americans first? Italians first? No, it should be: The weakest first! The most needy first!

Version: I find it difficult, with all the cruelties and crimes committed in the name of Jesus for the past 2,000 years. Jesus is a white man. Is it enough to just flip the signs and cast a Black actor?

Yvan Sagnet: I think with this casting, Milo Rau wanted to show that Jesus is neither white nor black or yellow, but just a person like any other. Whether a refugee or not, poor or rich, no matter their social rank. Milo Rau also cast women as apostles, whereas in the Bible, it’s only men.

Version: I’ve heard that with the film, a large activist political campaign is planned. What are the goals, and what will you do?

Yvan Sagnet: The film is part of the Revolt of Dignity campaign, a campaign with numerous activists and about 30 NGOs and organizations that address various issues, fighting against trafficking in women, sexual exploitation, for the environment and for workers‘ rights. It was Milo Rau’s wish to carry the film’s message forward sustainably for years. The film will give a voice to this campaign, which must continue after the film ends. The people he engaged for the film need to come together to continue the work. Thanks to the film and the movement that Mio Rau helped to build, we were able to find housing and work for many migrants. For example, my company noCap is also part of this campaign, which is continuously moving forward. The film will help make this campaign visible so that everyone can support it. noCap is looking for small supermarkets in Germany, France, and Switzerland to sell certified products and ensure that more and more migrants and workers have legal, dignified jobs.