Bernhard Cella / Version 5

I have a studio and a workshop. My studio consists of an archive I have built over the last twelve years, which revolves around topics and interests related to visual art. Books and publishing were already a central focus of my working method during my studies.

While still a student, I began creating temporary works—performative pieces driven by an idea—interventions that would then disappear. This working approach always left behind a mixture of material and documentation, raising the question: how should I deal with it? How does this material relate to the actual work? Publishing helped me develop new forms that made my working process legible, without simply tracing it.

For example, for the showroom of the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna at the Böhlerhaus across from Schillerplatz, I submitted a concept aimed at bundling my perception of production, reflection, and mediation into a visual-dramaturgical form. I set it up like a kind of game—the space was visible from floor to ceiling, like an aquarium, with three glass walls, a rear wall, and a floor as a playing field. The playing field was painted in a neutral blue and gridded in square meter areas. I sent out vouchers to 96 colleagues, inviting them to respond to one of the squares as if responding to a question. Within fourteen days, everyone could inscribe themselves in the grid structure in whatever way they chose. My interest was in attempting to create a structure, a model, that could provoke a situation and depict a climate that seemed to shrink a real-world down to model size. And then to play reality in this model for two weeks and enter into a relationship with others. I took on the role of game master. What astonished me most was how naturally the artists accepted the boundaries I had set. My grid was embraced. In a way, it was an attempt to develop a dramaturgical form that was neither descriptive nor representative but served as a trigger for something invisible.

For documentation, I photographed the floor and walls daily; the entire process was transparent and public. At the end of the fourteen days, I displayed fourteen square meters of documentation in the window—from the abstraction of a clear, empty space to the aesthetics of a fully grown vegetable garden. Some works were more, some less interesting and de facto a strange-looking structure emerged from this, which led—and this was my intention—to art destroying art.

“I ask you a question, give me an answer.” The answers ultimately took over and dissolved the space for the questions. And from there, the documentary aspect emerged—photos, notes, interviews. But what was the actual work? How does it become visible? Is that even possible within the art world? Or is it impossible? I followed the idea that publishing is essentially a result of conceptual art and started to explore this more deeply, developing various formats for it. In the beginning, I created dummies—one to three pieces. For “Ein Quadratmeter Kunst, for instance, it became a kind of leporello.

The possibility of understanding work on the development of new printed works, i.e. publishing in general, as an artistic practice in its own right has stayed with me ever since. Another example: with Annual Table on Art in Austria, I worked with data. A series of six screen prints, displayed as a frieze on the wall, illustrated various aspects of the annual cycle of Austrian art events (1993–1994). I collected the data myself using ten laptops, ten volunteers, and a computer program that we fed the information into. It addressed the relationship between information and complexity and also the question of how such information could be artistically visualized. What is exhibited? Who exhibits? Where? For how long? Is the artist male or female? And so on. I tried to translate this data structure back into a visual format, creating a kind of arrangement that played with the viewer’s gaze on various levels. Information can then serve as a pretext to reveal entirely different aspects, such as the rhythm of production or the relationship between different disciplines within visual art. A related artist’s book emerged from this, and three years ago, I was invited to exhibit the work in England. I was surprised at how current and little-aged it still seemed.

A book always demands effort—you have to read it, understand it, and be willing to engage with it. In Austria, during the 1990s, there wasn’t much interest in the book as a medium within the art world; it was traditionally perceived as an accessory to an artwork, rather than as an artwork itself. That perception has shifted somewhat over the past ten years.

If you like, this current archive here is the material of a body of work I have been developing for twelve years. Much of it deals with self-publishing within the field of visual arts.

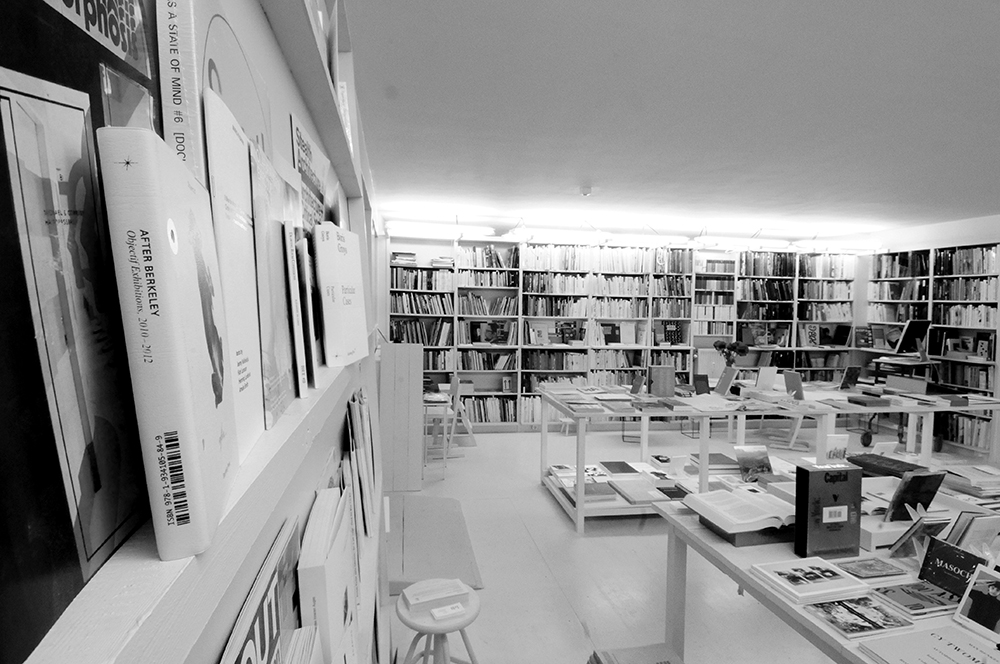

In 2007, I transformed my studio at Mondscheingasse into a “model of a bookstore at a 1:1 scale,” a kind of permanent installation in the tradition of conceptual art. The interior was designed as a monochromatic display of wood, plaster, paint, and light—that was it. I built display windows to emphasize the character and appearance of a storefront. Into this empty model, I began to gather publications, gradually densifying the space with printed works from the art world.

Working with model formats fascinates me because art itself, to me, always involves constructing a model situation in which all kinds of questions can be negotiated differently.

Starting in 2007, I took my time researching and bringing well-made printed works to Vienna. As the collection grew and was continuously shared with the public, a kind of density emerged that helped me channel questions I had as an artist into the public art sphere—but through a different format, with the book always serving as the interface. It was always about generating exchange with or through a publication. I actually built a kind of funnel into which these highly informed objects are poured, creating a perceptible compression. And these objects often offer rare information—many of these publications hardly ever appear publicly because their print runs are far to small. With only a hundred copies, you can hardly speak of a print run.

From the very beginning, I have always worked spatially, i.e. space-related. Dealing with the book as a creative material is essential for me. The question of how to deal with the book as an object preoccupied me early on. Once I had around a thousand books, other aspects also began to interest me, so I started working with color coding, sorting books solely by color. On closer inspection, this led to questions about the relationships that emerge from these color affinities: Does the color of a book cover relate to its content? What do black or yellow titles have in common—if anything? Many of these publications are self-published. This means the authors have significant influence over the design. There’s hardly anyone who doesn’t care what their book cover looks like. Generally speaking, publications in the art world are always externalized works.

Collecting, in this context, is both a necessary approach and a personal passion. It’s clear—once you dive into a subject like this, considering that book culture spans six hundred years of our cultural history, and you engage with the history of publishing, not only do ideas emerge, but also a different understanding of the material. And for me it was interesting that it is obviously a universal understanding and therefore has the potential to communicate in a certain way independently of the local. I’m always pleased when I can develop something that can be understood on another level. After I started working with color coding, I built large tableaux, arranging books into different formations, photographing them, and realizing them one-to-one as photographic works.

At Belvedere 21—then still the 21er-Haus—I often got feedback that sorting by color seemed “childish.” Too simple an approach? Given the sheer volume being published and the fact that hardly anyone can absorb all the different discourses happening at once, I found this playful approach to information—through a visual moment and, in a way, through retinal relaxation or stimulation—much more interesting.

When you see only yellow books, you don’t initially notice the titles but rather the different forms, shades of yellow, formats, the way typography is treated, and so on. It triggers a very different way of engaging with the material. It frees you from approaching it solely in a logical, intellectual manner.

In 2011, Agnes Husslein invited me to develop a concept for the museum shop, to implement what I had started in my studio in a new way for the institution. Initially, it was no more than an installation that responded to Karl Schwanzer’s architecture and marked the beginning of a process during which a collection with a specific focus emerged. We invited all players—museums, institutions, associations, individual artists, and galleries engaged in publishing in Austria—to present their publications there. The idea was to create an overview, to show what is being developed, exhibited, thought, and published across Austria. This created an assembly that offered a horizontal perspective on Austria’s cultural landscape—like laying out a terrain. It also revealed repetitions—topics that may have been handled better elsewhere—or small, highly specialized works. Others were trying out something entirely new.

In parallel, there was a continuous two-week event program. Especially for an exhibition venue like this, I found it important to show the diversity of productions—not necessarily what my generation or people I personally admire were making. I tried to develop a strategy that also incorporated historical facets of the museum itself. For example, there was the Grazer Autorenvereinigung, which was very active at the 20er-Haus in the 1970s. Literature played a major role in visual arts until the mid-1980s. For their thirtieth anniversary, we organized a kind of marathon reading together. I think it lasted four and a half hours and allowed me to experience a generation that I and many of my contemporaries had never had personal contact with in this form before.

Simply collecting books is just one aspect. If you don’t constantly engage with the material and put it to use, nothing happens. It just sits on the shelf. I even built an extra room where I can pull out the material and repurpose it for different projects, like photographic works. I also created an inventory, which I performed at Kunsthalle under the title Lucca, I’m reading my inventory. It was a complete list of all titles—I think around twenty-five thousand. I got to one thousand four hundred, and then we stopped.

Re-using highly informed objects as material requires, on the one hand, knowing the content and, on the other, handling the material qualities in a new way. For me, this studio here is like a laboratory—a kind of experimental setup where real situations can be played out in a model situation.

But I’ve also developed works related to the semi-public nature of the studio. In 2010, I created a series of 58 tapestries, all based on the fact that books were stolen from me. I started compiling a list of the stolen books and later wove selected covers into tapestries, which now form a new group within my collection. For me, this was a logical approach because it helped me stay in the process.

One of my rules is: the last copy of its kind always stays in the collection. This means there are books you can buy and others that are not for sale. I’ve often exhibited out-of-print, rare, or valuable artist books that were gifted to me.