Hugues Mousseau / Version 4

Frank Zappa and his Curiosity about Edgar Varèse

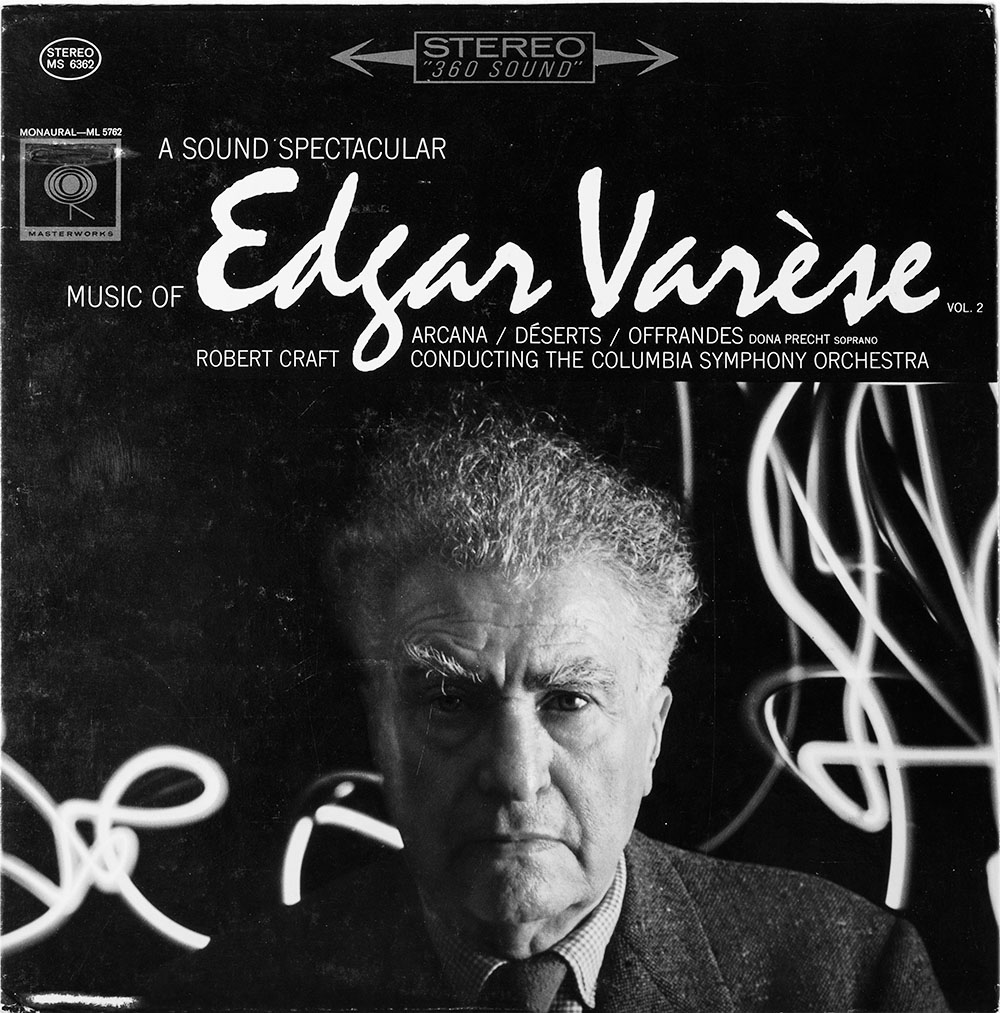

Zappa is a fascinating, unique case. He is the only rock icon who also felt completely at home in classical music. He composed classical pieces so relevant that none other than Pierre Boulez conducted them. That’s why he was so envied and hated by other rock legends. They could sense right away that he was superior to them. That’s also why they were relieved that he didn’t take up too much space Nevertheless, they always feared a little that his elitist music might gain wider acceptance. Because there was an even denser, more impermeable border between serious and popular music back then, almost nobody in the classical scene knew Zappa. But Zappa was deeply interested in musical issues. Sure, he was also an entertainer—but with sophistication and biting humor. He set the bar higher than any other rock musician. And from a very young age, he was drawn to Edgar Varèse. At 16, he wrote Varèse a letter—very modest. He was curious about this obscure, radical French composer who had been living in New York for decades. Varèse kindly replied, saying he would be happy to meet him if he ever came to New York. Unfortunately, that never happened, as Varèse passed away in 1965.

But there was a connection, an instinctive fascination Zappa had for Varèse, because he sensed that something was happening there that he could learn from. Other rock musicians didn’t engage with such topics at all. Zappa—who, by the way, strictly forbade drug use among his musicians—was operating on a completely different plane. He was also interested in the School, in Bartók, and, of course, in Stravinsky, but Varèse was special to him. I think he was drawn to that boundlessness in music.

Varèse: Vulcanus of Modernity

The son of an Italian father and a French mother, Edgar Varèse felt too constricted in Europe very early on. “Paris? A city of intrigue,” he once said, scathingly. In 1915, he moved to New York. While Varèse had internalized the iron discipline, foundations, and strict rules of classical music, he also knew that some composers, particularly Berlioz and Debussy, had managed to break free from those forms. Not all composers are capable of that. Even a genius like Schönberg couldn’t do it; he worked within a certain framework. With Varèse, it was different. Vulcanus of modernity: Varèse knew no boundaries, and his works bear titles like Amériques—plural; not in a geographical sense, but meaning all those unknown continents or regions where anything is possible. It meant: “I am going to discover a universe now.” Then there’s Arcana, which, in my opinion, is his most important work, as significant as Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du printemps, Bartók’s Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta, or Debussy’s La Mer. Varèse’s Arcana is truly among the eight or ten most important orchestral works of the 20th century. “Arcana” means “secrets,” something that cannot be decoded but can certainly be explored. This also has something to do with Friedrich Nietzsche’s „Hinterweltler“. There are other Varèse pieces, such as Intégrales or Déserts, that also take music to incredible places, but Arcana has a unique intensity and formal perfection. It is completion in every sense. By the way, Arcana should only be listened to as conducted by Jean Martinon with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. No other recording can compete with it.

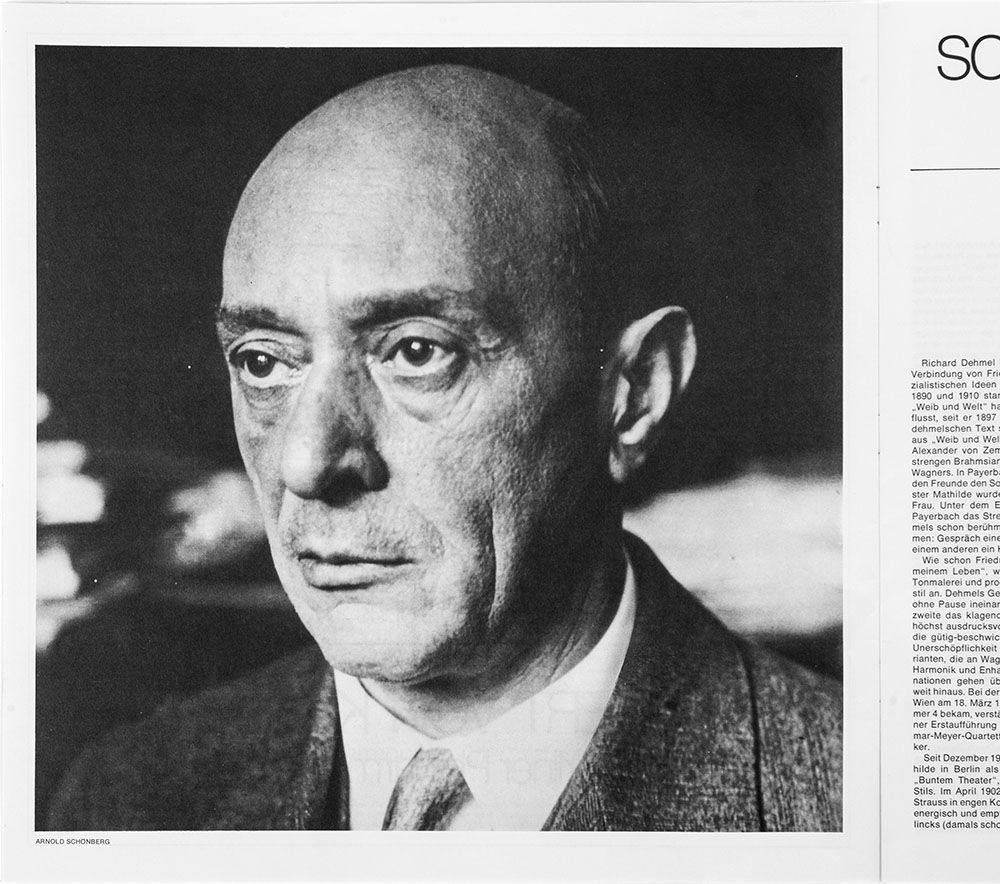

Varèse never felt bound to a tradition like Schönberg did. Schönberg, the founder of the Second Vienna School, was absolutely part of the Bach-Beethoven-Brahms tradition, where strict formal rules applied. Schönberg’s syntax comes primarily from Bach and Brahms, with a bit of Beethoven. You don’t find anything like that with Varèse. I wouldn’t say Varèse was a greater composer than Schönberg, but he was certainly freer. After him, aside from Stockhausen and György Kurtág (who is still alive), there has been no composer as aesthetically free as Varèse. The freest of them all, I believe, remains Debussy. Varèse actually owes more to Debussy than to Stravinsky. The German audience hardly understands Debussy. A very musically knowledgeable man once told me that Debussy’s music had no backbone for him. And I understand exactly what he meant because German-Austrian music has formal structures that are simply not present in Debussy’s work—you neither see them, hear them, nor feel them. That’s why, with Debussy, it sometimes seems as if there’s no ground beneath your feet anymore. And that is precisely Debussy’s greatest revolution, which Varèse appreciated and, in a way, carried forward.

The Arcana is essentially a metaphor. This 18-minute work for a large orchestra is like a volcanic homage to the passacaglia—think of Bach’s titanic passacaglia for organ—one of the most rigorously structured musical forms. And it is a fascinating paradox that such an ultra-strict form can give rise to the freest music imaginable. Schönberg, for instance, could never have done that. Schönberg could only disapprove of and despise this kind of music.

Arnold Schoenberg and the (So-Called) New Vienna School

Schoenberg was convinced that German-Austrian music was the highest of all. And Schoenberg was a dogmatist. A genius, an inventor—but very, very dogmatic. Alban Berg was different. Berg was the lyrical one in this trinity with Webern. Schoenberg was the theorist, Berg the poet, even though he also composed highly structured music, like the Drei Orchesterstücke, Op. 6. And Anton Webern was, in a way, the researcher, the one who took things a step beyond. His music is highly abstract, showing almost no sensuality. It’s a kind of “cosa mentale”—everything was intellectualized with him. I find it fascinating how this trinity—Schoenberg, Berg, Webern—expresses itself, because the Vienna School, as such, doesn’t really exist.

Webern is particularly fascinating because he only wrote very, very short pieces. Consider this: Varèse’s entire body of work is barely longer than Mahler’s third Symphony. And with Webern—if you exclude the many songs he wrote—it’s the same. No composer has ever written with such compression as Webern. Only masterpieces, but on a very small scale. Some of his movements last no more than 30 seconds, yet in those few seconds, almost as much happens as in an entire movement by Mahler or Bruckner. Compression was not Schoenberg’s thing. He was preoccupied with completely different concerns—syntax, forms, structures, or biblical themes, like in his final, unfinished opera, Moses und Aron. The central theme of this hieratic work is the “unspeakable”: Moses conceives the law but is utterly incapable of conveying it. He is completely unable to communicate and needs a messenger—that’s Aron. Aron is an idiot, so to speak, but he has this talent for conveying Moses‘ message to other people. Moses und Aron is almost autobiographical, because even in Schoenberg’s own time, his music was criticized as abstruse and hermetic. Apart from his early works, which are still very post-Romantic, heavily influenced by Wagner, Schoenberg’s music possesses an iron severity—I would almost call it a fundamental bitterness. This kind of seriousness is something you don’t find in Berg, for instance. Berg has a completely different dramaturgy, and his works create a much broader space for lyricism, sensuality, even eroticism. Not so with Schoenberg. There are, of course, a few exceptions, but I can rarely associate Schoenberg’s major works with poetry.

Some people are exactly as they look. [Shows photos of Schoenberg, Berg, and Webern.] I really believe in facial morphology in this case. Schoenberg looks like his music sounds—busy, dry, humorless. Webern, on the other hand, is already very metallic, highly abstract-intellectual. This is a beautiful photo, yes, a very typical Webern photo. Pure uncompromisingness, but without the bitterness that one finds in portraits of Schönberg. And Alban Berg was an entirely different character. He embodies this torn, but also hedonistic Viennese culture much more than the other two. Of the three, he is the one closest to Gustav Mahler, not least because he had that connection to life and to beauty in life—though always intertwined with his instinctive inclination toward tragedy.

Stravinsky as Picasso’s Alter Ego

Stravinsky shows absolute parallels to Picasso, both in character and as an artist. Just like Picasso, he explored all the styles of his era—and every time, he was successful. While Le Sacre du printemps, Petrouchka, Les Noces, and the Psalmensinfonie are Stravinsky’s most important works, he composed many other pieces where—like Picasso—he experimented with everything, including musique sérielle and neoclassicism. And the parallel goes even further: both were extremely stingy. Stravinsky even charged money for interviews, despite being incredibly wealthy—almost out of principle.

Pierre Henry, the Pope of Musique Concrète

When listening to Variations pour une porte et un soupir by Pierre Henry—literally “Variations for a Door and a Sigh”—one immediately thinks of highly sophisticated works like Bach’s Goldberg Variations, Beethoven’s Diabelli Variations, or even some of Max Reger’s more indigestible pieces. Henry’s Variations sound almost Dadaist, but he creates an entire cosmos out of these noises, with a carefully thought-out and subtle dramaturgy. It is absolutely structured, with a millimeter-precise, grand arc. I would almost say with a unique syntax. It may be his most symbolic piece. I wouldn’t necessarily call it his most important work—there are many other fascinating pieces by Pierre Henry—but I believe Variations pour une porte et un soupir defines him, his spirit, and his incredible grit.

Stockhausen, the Wagner of Modernity

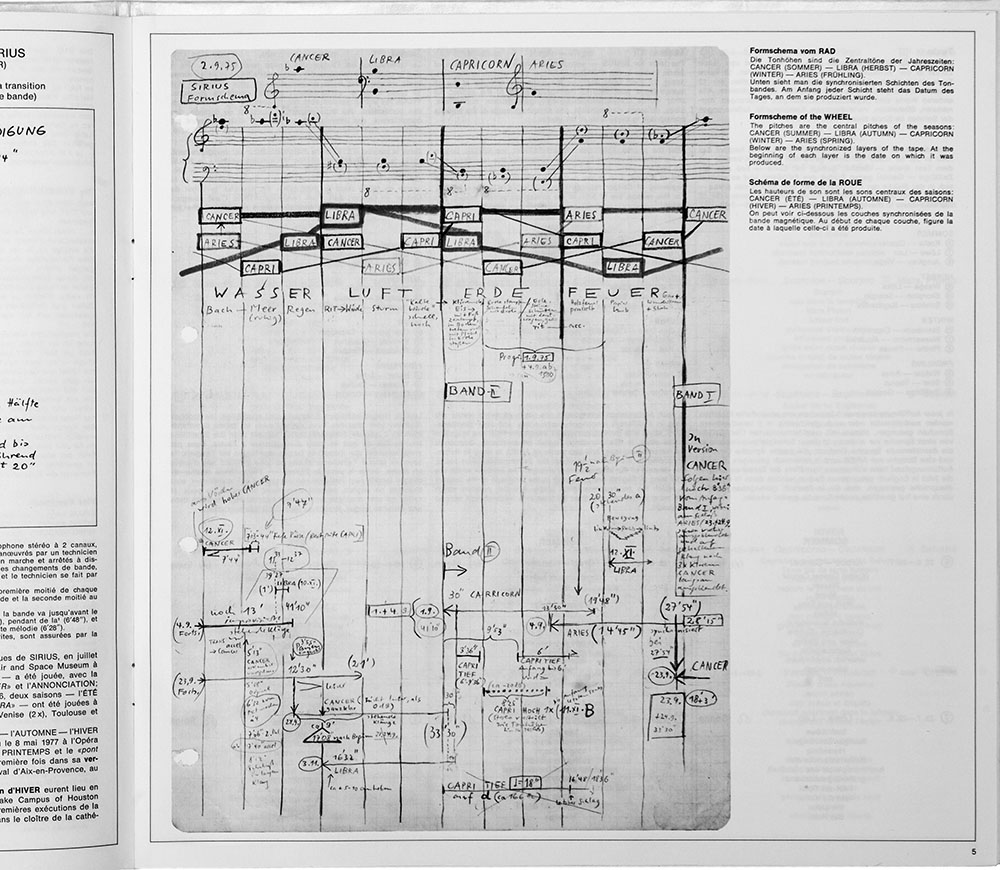

And then, of course, there’s Karlheinz Stockhausen—a continent unto himself. But Stockhausen presents a different kind of challenge—I would almost say a post-war challenge. Stockhausen was an orphan, born in 1928. He experienced World War II firsthand as a child, in a tragic way, and grew up on a farm. He left the earth, let’s say, he left the universe completely, he composed for other galaxies rather than for humans, so to speak. He dared to do things no one else of his time attempted. His influences came, on one hand, from Varèse, but also—though less explicitly—from Olivier Messiaen.

Stockhausen studied briefly with Messiaen in Paris, one of the greatest and most undogmatic composers of the 20th century. As a teacher, Messiaen was a key figure—Boulez, Xenakis, and Pierre Henry also studied with him. He gave his students complete freedom; each could develop their own path. But Stockhausen carried an implicit weight—the burden of being a German composer. Even the name itself: Stockhausen. I believe your name shapes you. If you’re called Stockhausen, you’re immediately stamped as a radical German composer. How do you deal with that? Especially as someone from his generation? It wasn’t so difficult for an Italian like Nono, a Frenchman like Boulez, or a Greek like Xenakis. But for a German—who was already a bit of a wild one from a young age, “une tête brûlée”, a hothead—it was difficult, almost unsolvable. Think about it: what other significant German composer of his caliber emerged after the war? None. Henze is nothing against it. Henze always talked about revolution in a high-sounding, big- snouted way, but he was always a philistine. Stockhausen, on the other hand, was more like a modern Wagner. And like Wagner, he had a tendency toward megalomania. Like him or not, Stockhausen is indispensable. Boulez and Stockhausen had great respect for each other, even though they composed in completely different directions. They were on equal footing. But Stockhausen was also—and still is!—the bourgeois terror par excellence.

This guy, who composed for planets and the universe, remained loyal to his home near Cologne until his death. Stockhausen lived in Kürten near Cologne, where the famous WDR studio for electronic music was located. At some point, he bought himself a big, modern house and built his own studio, where he could compose with complete freedom and independence. He traveled a lot—to Asia, North America, Latin America, Africa. He went everywhere, but never as a tourist. He deeply immersed himself in ethnic music from India, Japan, and China, yet he never left his Cologne homeland. Mentally, he was totally free. An interesting case, I think, when it comes to identity.

Magma: A French Path

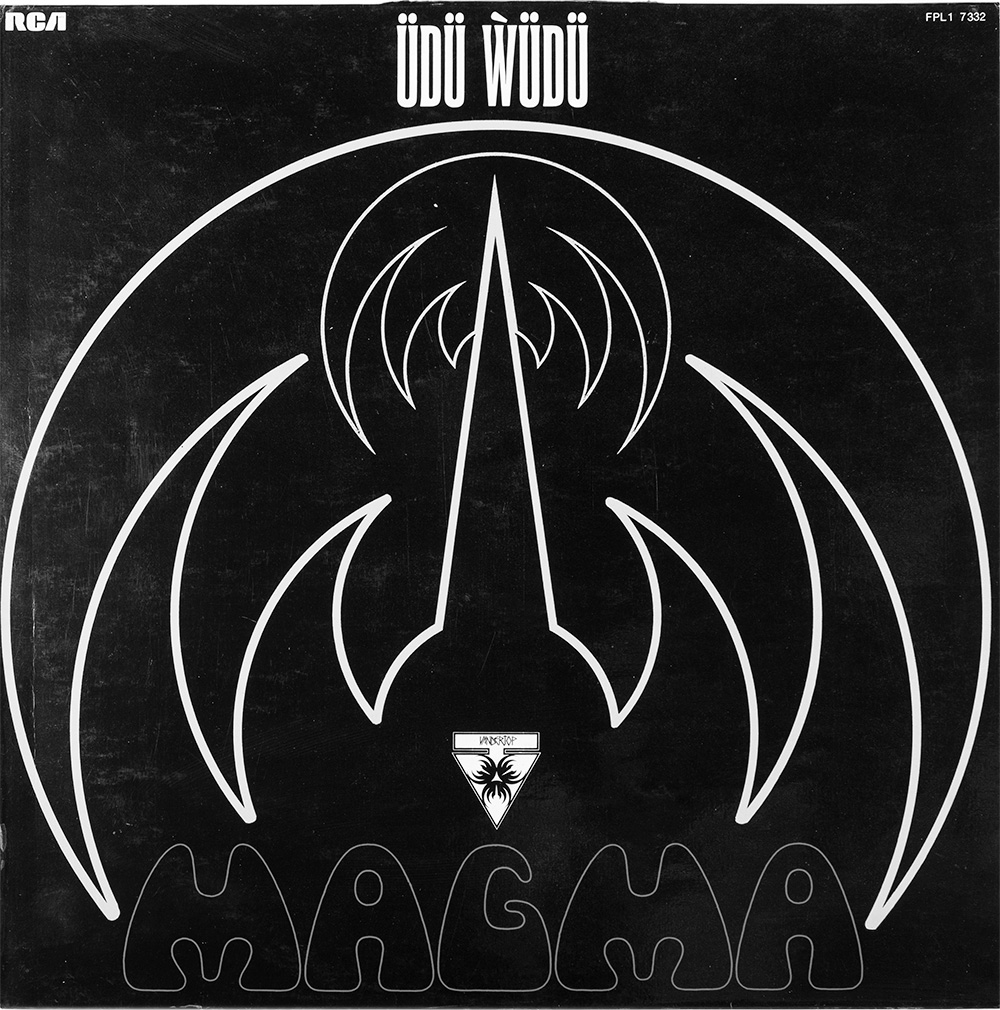

French rock bands were never taken seriously by the English or Americans. Simply ignored. The only non-Anglophone groups that managed to gain lasting respect in this field were German bands—who, with the exception of Can, had no other choice but to make purely instrumental music. Tangerine Dream, Klaus Schulze, Popol Vuh, and Kraftwerk—because German as a vocal language was considered an absolute no-go. Singing in French didn’t make things any easier for a rock band. To get around this obstacle, Christian Vander—the founder, drummer, and leader of Magma—invented the artificial language Kobaïan, with album titles like Köhntarkösz, Ẁurdah Ïtah, and Üdü Ẁüdü.

Magma was more of a collective—similar to Zappa— and so far perhaps 80 musicians from all horizons have taken part. The fact that Christian Vander was always a hothead is euphemistic. Like Zappa, he knew classical music inside out—he studied Wagner, Stravinsky, Bartók, Orff, and Messiaen just as deeply as Coltrane. He never saw himself as a pure rock musician, either. He always worked with musicians from jazz, free jazz, or classical music—never with those who were strictly rock musicians. Rock was always too narrow, too one-dimensional for him.

Magma was a “scare for idiots”, because many were frightened by the band’s aesthetics and symbolism, and it was quickly rumored – because of these umlauts, this fascination with the barbaric, the Teutons and the runes – that Vander was the guru of a fascist sect. The brute rhythms, the grunting, the primal sounds were intended to unfold and convey the elemental power of the music, ambitious but not too complex. So Vander managed with ease not just to appear as a little Frenchman with his beret and baguette. Even today, you’ll find Magma fanatics in Michigan, Brazil, and Japan, just as much as in Europe. If you’ve never heard the 18-minute De Futura, you haven’t heard anything.

From Ockeghem to Kurtág: No Progress

With Ockeghem or Josquin des Prés, the leading figures of the Franco-Flemish school (circa 1420 to 1520), everything was already in place. Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Wagner, Debussy, Stravinsky, Varèse, Stockhausen, or Kurtág do not represent any progress at all. Music has certainly evolved, but not improved. And Ockeghem, in the polyphony of his Catholic Missa Prolationum, or Josquin des Prés, in his late Missa Pange Lingua, each composed for only eight singers, achieved something insurmountable. These are highly complex compositions, sometimes as intricate as Bach’s The Art of Fugue, yet just as accessible as Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony. The Franco-Flemish school was not just three composers, as with the Second Viennese School, but about 50 composers of equal rank, all recognized as geniuses in their time. During its golden age, in the region between Ghent, Bruges, and Lille, there was an extraordinary level of competition for around 70 years. And that is unique in the history of music, because I don’t think there have ever been so many geniuses in such a short space of time. From today’s perspective, one might get the impression that they all sound alike, but that’s not the case. Everyone had their own style.

Brahms Meets Vienna

Starting in the 18th century, Vienna took on an imperialistic role in music, a position it maintained until World War II. From Haydn to Berg—passing through Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Brahms, Bruckner, Mahler, Wolf, Schoenberg, and Webern— Vienna was the city that all composers dreamed of and in which they wanted to assert themselves or establish themselves.

On the other hand, all the important composers living in Vienna were either deadly unhappy, frustrated or despised there. Vienna humiliated, ignored, exiled, and silenced countless composers. Very few were truly loved by the city over the long term. Vienna grew tired of its composers and their styles quickly. Brisance was only tolerated there for a short time. After a while, it was punished.

Some composers never engaged in provocation, such as Palestrina in Renaissance Rome—or Brahms. Brahms, the North German, was practically the only composer who was genuinely and permanently happy in Vienna. When he settled there for good in 1872, after an initial stay, he quickly became an idol. He always adhered to rules. He could be brilliant, and his genius lay in his unique ability to exploit rhythmic asymmetry, harmonic ambivalence and formal ambiguity. But always within an academic framework. For him, this was a kind of emotional security. And that probably has something to do with the fact that he grew up in Hamburg and had to play the piano in brothels at a very young age. The trauma must have been considerable because Brahms was never able to maintain a lasting relationship with a woman. Never. Instead, he visited prostitutes throughout his life.

This tragedy is reflected in his music. Despite its unmistakable melancholy, it feels eerily controlled, contained, commanded. Brahms’ music does not take formal risks like Beethoven’s or Schumann’s, does not plunge into abysses like Schubert’s, does not have the cosmic breath of Bruckner, nor the grand madness of Wagner. Brahms always composed with stylistic and aesthetic propriety. His innovations—Arnold Schoenberg was among the first to recognize them—were always veiled. Brahms was not willing to openly break rules. For that, Vienna remained grateful to him until his death.

The German Lady, Beethoven, and the Hitler Salute

I have lived in Berlin for 18 years and have never regretted leaving France and Paris for a second. And yet, even after all these years, I feel as if I’m in Nicaragua or Indonesia. For a Frenchman, Germany is no less exotic than Manchuria. I love life in Germany, but it’s always an experience for me to see how people think, communicate or react here. I feel like I’m in a completely different world. The possibilities for astonishment are simply endless.

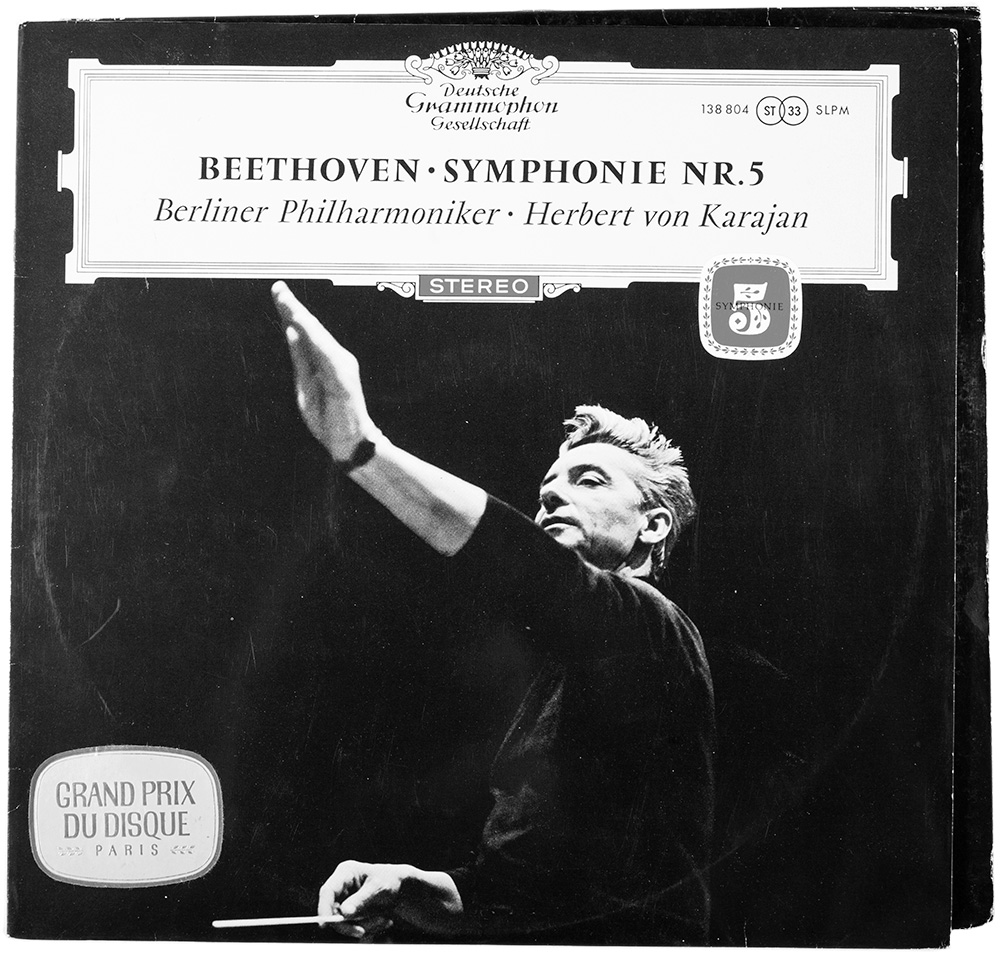

The other day, a German lady walked into a record store where I occasionally help out the owner, a friend of mine. She was in her mid-sixties, very nice and polite, a bit conservative. She was looking for a gift for someone from abroad, something representative of Germany—perhaps a Beethoven symphony. I spontaneously and generally recommended Simon Rattle with the Berlin Philharmonic. She didn’t seem entirely convinced. Although she didn’t say it outright, I could sense that it wasn’t quite German enough for her. The Philharmonic, sure, but an English conductor for Beethoven…

Her skepticism wasn’t really rooted in aesthetics. She was a bit contaminated by today’s globalized world culture. She wanted something she had heard about in the media, but also something reassuring, something that would make her feel „secure,“ at home. I then suggested a recording by Wilhelm Furtwängler. She didn’t want that either: too old, too historical, too outdated. Then I suggested Karajan—the legendary 1961/1963 Deutsche Grammophon cycle. „Yes, Karajan, very good!“ she exclaimed enthusiastically. „Perfect!“ And then, jokingly, I pointed to the cover photo and added, „With the delightful Hitler salute to go with it!“ (Karajan’s elevated conducting gesture in the cover photo—taken from below!— inevitably reminds of the Hitler salute). Instead of laughing or reconsidering whether it was such a great choice after all, she was shocked, frozen, as if she had been electrocuted. The CD, which she had just embraced with such spontaneous enthusiasm, she suddenly wanted nothing to do with and quickly placed it back on the shelf. „Oh no! That won’t do, not at all!“ She refused to touch it again. She nearly crossed herself.

I could understand her reaction, but I hadn’t expected such sheer disbelief, such panic. What’s interesting here is that she hadn’t even noticed the Hitler-salute resemblance at first. Had I not pointed it out, she would have overlooked it entirely. Even more intriguing, I think, is the discrepancy between the spontaneous acceptance of a cultural product—almost like a brand (Karajan conducting his Berlin Philharmonic)—and the almost childish rejection of it once someone else casts it in a different light. I have had many such bizarre experiences in Germany.

That album cover, by the way, is worth discussing. It speaks volumes. How it came about is no longer a mystery to me—it’s quite clear. Karajan’s complete Beethoven symphony recordings were released in 1963. Every album—except the Ninth—featured the same Hitler-salute-like gesture on the cover. I am certain that this subliminal similarity, this unconscious signal, was not intentional on the part of Deutsche Grammophon. But it also wasn’t mere coincidence. And the low-angle shot is, of course, significant. The economic miracle was already in its final phase. Politically, Germany was still a dwarf. And I am convinced that Germans at the time longed for a leader—one who, of course, couldn’t be political. But a cultural leader was conceivable and acceptable. In the early 1960s, Karajan and his Berlin Philharmonic perfectly fulfilled this vague and suppressed desire. He was the right conductor at the right time.

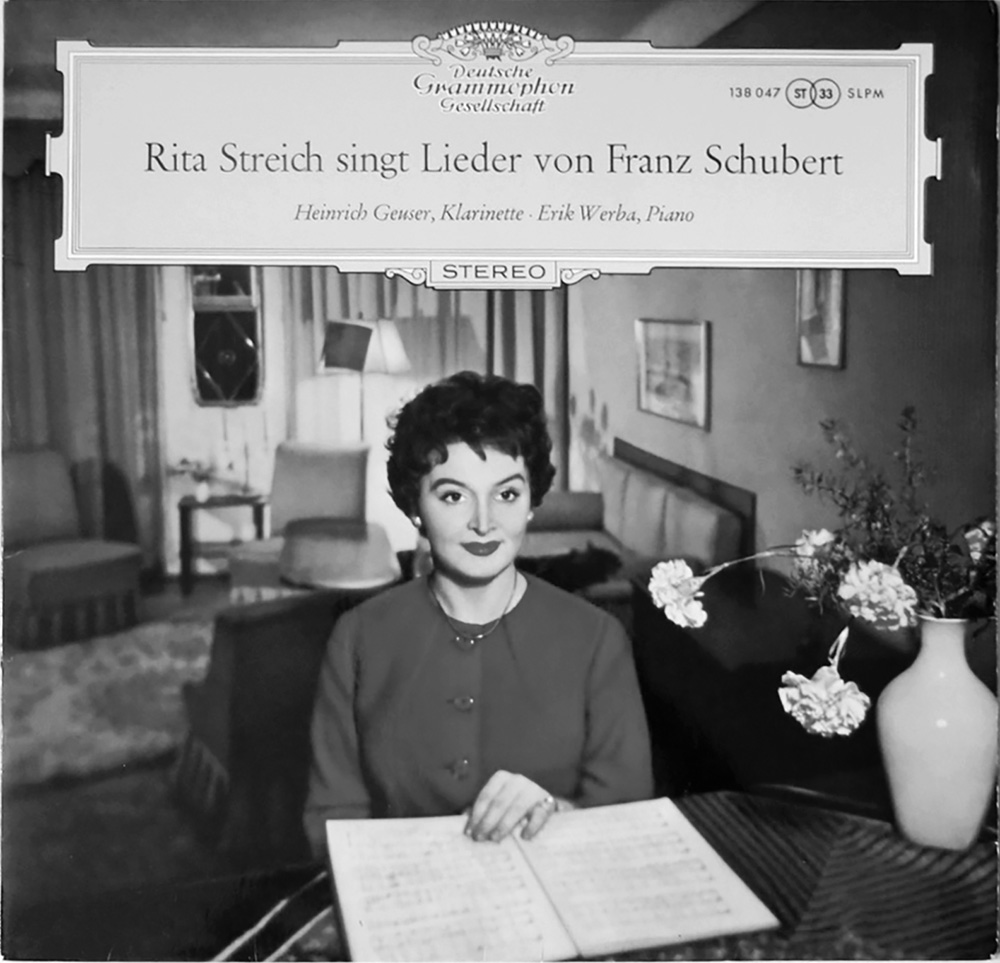

And the longing for a different kind of imagery among Austrian cultural consumers of that era is evident in the cover of Rita Streich’s album—a beautiful, idyllic, kitschy world of the 1950s, offering a refuge for those who saw themselves as victims. I think it speaks volumes. And these covers remain a piece of history.

www.sonymusic.at

www.universalmusic.at

www.magmamusic.org