Belinda Kazeem-Kamiński / Unearthing. In Conversation / Version 4

Unearthing. In Conversation

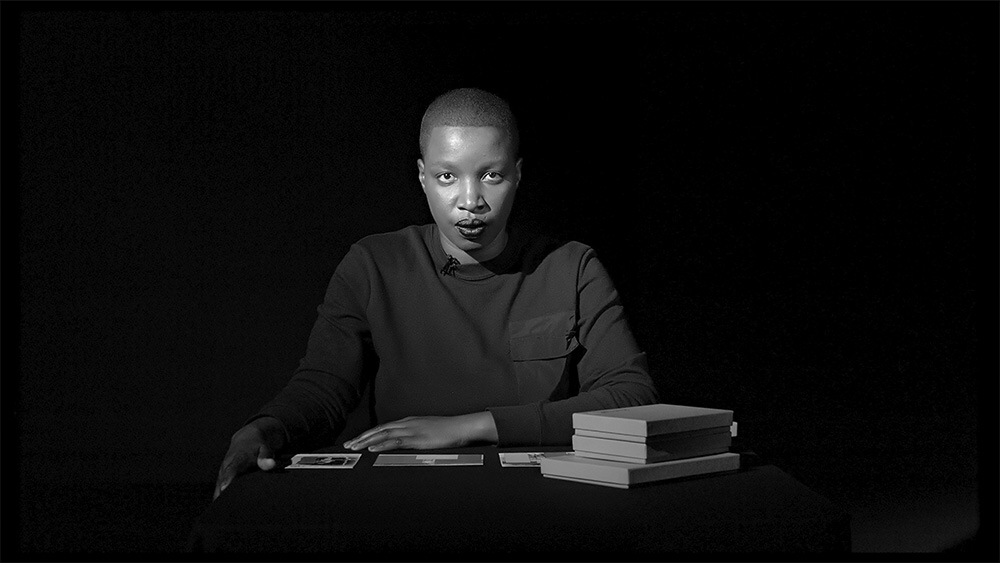

Imagine you are in an empty movie theater. You’re not sitting; instead, you’re leaning against the sidewall. The projector light is on, illuminating a table and a chair in the space between the rows of seats and the screen. Other than that, everything is dark. The performer enters the space, carrying four small cardboard boxes in her hands. She sits on the chair, slowly turning her head from left to right and back again, then fixes her gaze on the movie seats. Silence.

This is in remembrance of those who are yet to come.

This is in anticipation of those who are here.

This is a conversation with all those who were. We are.

The idea for Unearthing. In Conversation emerged from an encounter with photographs taken by Austrian-Czech ethnologist and missionary Paul Schebesta (1887–1967) in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo during the 20th century. Initially conceptualized as a ten-minute live performance, the work later developed into the video discussed here.1 It was first shown as part of the exhibition Hauntopia / What If at the Research Pavilion in Venice.2

Unearthing. In Conversation reflects a process of summoning, using archival material to relate performatively to the past. Central to this work is the question of how theoretical-artistic engagement can be used to initiate conversations and negotiations around the reverberating effects of colonialism—raising questions about the connections between past, present, and future without succumbing to the voyeuristic and exoticizing desire for the suffering Black body.3 To unearth something means to bring forth what has been buried in the past. But things may not necessarily be buried deep beneath the surface—rather, one’s perspective on what is buried is crucial. What remains invisible to some is impossible to shake off for others. The aim of this process is to confront whatever emerges, to find means of expression for the unspeakable.

This excavation and illumination are not developed as solitary practices in the video, but rather as communal acts that disrupt linear conceptions of time. Yet, despite all desires for completeness and consolidation, the work must remain fragmented and incoherent.

It begins with a visit to the exhibition Ware und Wissen at the Weltkulturen Museum in Frankfurt. I am there because I am working with a group of art mediators. As I walk through the exhibition, I notice a photograph. It depicts a white man—later I will learn that it is Paul Schebesta—his left arm extended over the head of a Black man beside him—I have not yet been able to find out his name. I cannot help but look into the man’s eyes. He stares directly at the camera—at me. A strange sensation overtakes me. I feel as if I am stuck between times, thrown back and forth between colonial past and a racist encounter the day before. It reminds me of something I have not experienced myself, yet it feels eerily familiar.

Back in Vienna, I go to the National Library. I find more photographs by Schebesta, books in which he writes about his research. I study his poses, the expressions of those depicted, their gazes. And then I find him again—the same pair of eyes, the same direct look into the camera—at me—the same urgency communicating something I do not yet dare to decipher. Once again, I’m haunted by the effects of colonial violence and its persistence in the present.

Months pass before I begin working with the material. Months in which I see the images in my mind’s eye yet do not know how to even approach them. I search for a representational strategy that might allow me to counteract the violence embedded in the material. Something that could adequately respond to Schebesta. Something that might soothe my discomfort.

Let me take you back to the opening scene. The movie theater. Table and chair. The projector light. The performer. She opens one of the cardboard boxes in front of her and begins to speak.

The first time I encounter you is in Frankfurt. 2014. I look at old ethnographic material, photographs taken by an ethnologist and his accomplices. There is a connection, something that resonates within me: the immediacy of a colonial flashback, an uncanny, lingering familiarity. My gaze meets yours. I wish you would open up and tell me what you were thinking as you stood there. I wish the thoughts of your past could pierce through the materiality of representation, that they could creep into my present and transfer themselves onto me every time our gazes meet: I want to know what you think.

How can I speak to you, you, the people in the photographs? How can we communicate? As I try to articulate my questions to you, it feels as though others—ethnographers, missionaries, photographers, authors—stand between us. Their words, their photographs, their presence. There is a proverb used in various African countries. Quickly translated, it says: “Until the lions have their own storytellers, the hunters will always have the best part of the story.” So tell me, how do I access your story? And what if I refuse to cast you as the hunted and instead seek to bring forth the moments in which you are the hunters?

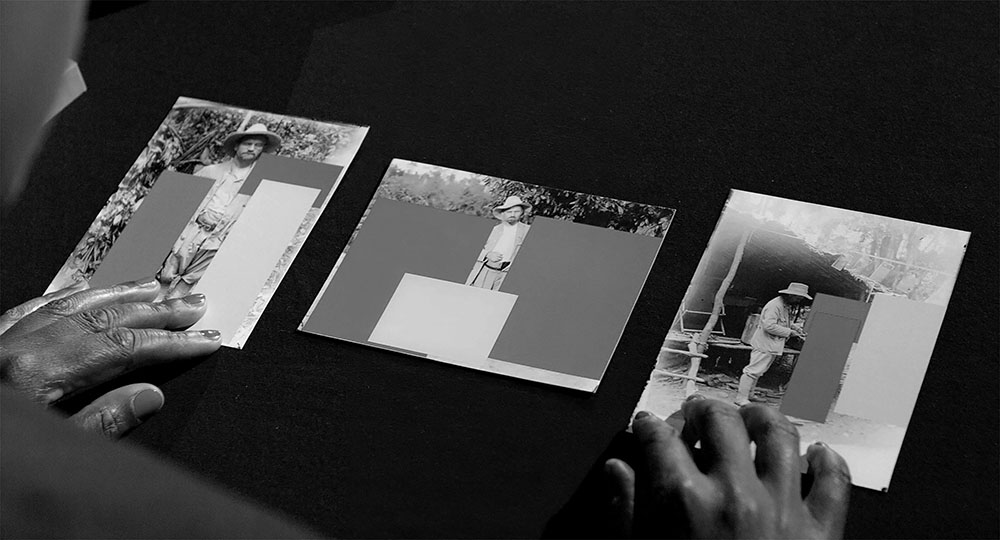

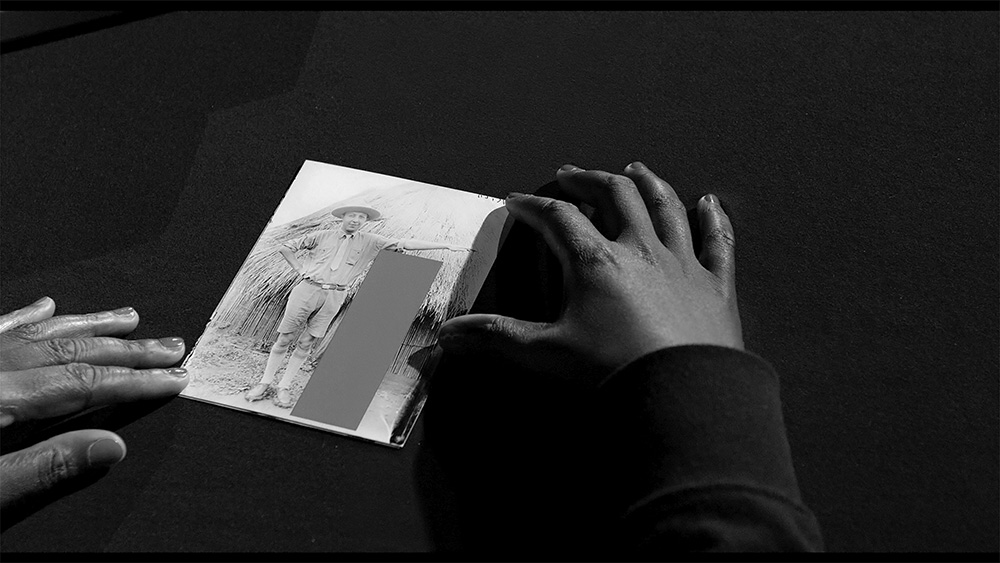

Some people read my early attempts as Pop Art. Others say my collages remind them of Baldessari… as if that were the reason I use red, blue, and yellow rectangles… Red, blue, and yellow—the colors of the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s flag. What does it mean to cover you with the colors of a nation that discriminates against you and questions your belonging? And besides, I despise flags… But it’s not about the colors I used; I doubt my chosen strategy. Alongside drawing attention to the ethnographer, I wanted to protect you, to shield your images from the gaze that has persisted since the first colonial encounter. A gaze that still invites and enables people to become colonial agents. Yet by doing so, I have obscured you, made it impossible for you to look at the viewers, to look back at them.

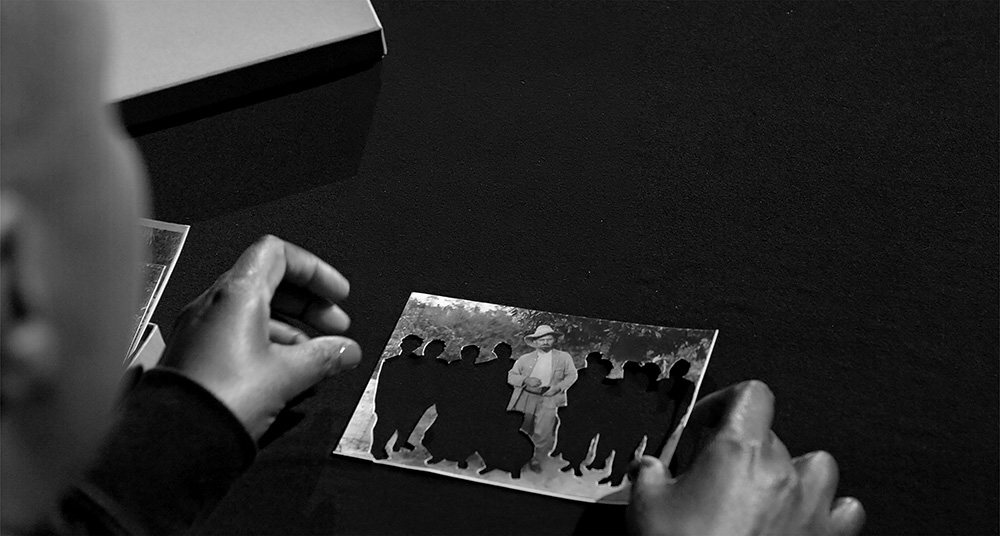

Back to the photographs—I focus on the ethnographer in your midst. “Who is this guy?” I think. Lips pressed tightly together, eyes obscured by the shadow of his hat—actually, by the shadow of both his hats.

I need time to realize he is signaling something. As I will discover, Schebesta’s pose repeats across different bodies, times, and contexts. In choosing to freeze this moment in space and time, he wants his imagined future audience to immediately grasp the message he is transmitting. As I look at the pictures, the need to resist becomes stronger and stronger. How to resist through looking? How to develop a resistant gaze?

It’s unbelievable. How did he manage not to mention the Belgian colonial system? There are no traces of it in his texts—at least not in the ones I’ve read so far. It’s as if he existed completely outside of time and context, moving through a forest misaligned in history, a space seemingly untouched by the colonial world. If it weren’t for the photograph of the Belgian colonial officer, nothing would point to a colonial system at all. Schebesta moved within his own imagined version of the Congo, a place that, at the time, was called the Congo Free State…

My aim is to focus on Paul Schebesta and his accomplices, but the effect is that I participate in your erasure; I quite literally cut you out of the frame.

At first, I leave the cut-out spaces empty. I can painfully feel your absence. Then, I place a mirror underneath. I want the viewers to confront their own presence, their own perceptions, thoughts, and knowledge.

The Congo and its people functioned as projection surfaces for European colonial fantasies. To conquer the Congo, certain measures had to be taken. A social identity of the Congo had to be constructed—the homogenization of its people. A spatial identity had to be created—the imagination of the Congo as vast and empty land. This enabled the writing of a colonial script that made certain practices—land theft, mass murder, terror, forced labor, Christianization, the severing of limbs—acceptable. But in applying these representational strategies, I equate you with the land, once again.

I cannot discard the cutouts—your images. And as I look at them, I realize that despite all my efforts, this is not about bringing Schebesta into focus. I cut you out of these photographs because I cannot leave your images as they are: lined up in a row, just as you were arranged; embraced by the ethnographer; placed next to a dead gorilla because Schebesta couldn’t resist capturing the analogy between monkeys and Black people—an image that fueled colonial fantasies and still does.

I gather your images, hold them together, and wait for the day when I will be able to create another context for you—a space that might be less violent, an environment that could be a home.

You used a Piki-Piki pipe against Schebesta. He recounts that he found one when he entered one of the dwellings to collect things—objects that would later end up in Western museums and collections. Filled with the belongings of an enemy, the Piki-Piki pipe protects against possible violence. It disempowers the enemy. But since he takes his presence for granted, Schebesta doesn’t even think about the fact that you felt the need to protect yourself from him. I concentrate on the ghostly, on what makes me return to these images again and again. The immediacy of colonial flashbacks, the restaging of processes of being made other. I need your presence. You accompany me while I try to find resistant ways of looking. I will call you. As I research, I become part of your army of insistent echoes. Insistent.

(Unearthing. In Conversation, 2017)

1For a text by Renate Lorenz on Unearthing. In Conversation, see http://www.sixpackfilm.com/en/catalogue/show/2427

2 The exhibition was curated by Renate Lorenz and Anette Baldauf. It featured works by students in the PhD-in-Practice program at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, exploring echoes, unfinished stories, and violent pasts. For the accompanying publication and the glossary of key terms conceptualized by the artists, see: https://issuu.com/academyoffineartsvienna/docs/hauntopia-what-if_zine_web

3 For a more in-depth engagement with the connections to the field of Black Studies and theorists such as Christina Sharpe and Tina Campt, see: Kazeem-Kamiński, Belinda (2018): “Unearthing. In Conversation. On Listening and Caring.” In: Critical Ethnic Studies Journal. Edited by Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang. http://www.criticalethnicstudiesjournal.org/ and Bayer, Natalie / Kazeem-Kamiński, Belinda / Sternfeld, Nora (2017): Curating as an Anti-Racist Practice. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter/edition Angewandte.

All photos: Stills from Unearthing. In Conversation, 2017 (13’)

Performance, concept, editing: Belinda Kazeem-Kamiński

Camera, editing: Sunanda Mesquita

Sound, lighting, editing: Nick Prokesch

Production, assistant director: Liesa Kovacs

Text editing and translation: Belinda Kazeem-Kamiński