Fatih Aydoğdu / Version 2

Paratactic Commons: Seeking Alternatives to Autocratic Systems Through Art and Creativity

Art and Cultural Production in Istanbul After the Gezi Uprising1

Turkey’s emerging art and cultural scene—with its festivals, biennials, and art fairs—is no longer an insider secret, either locally nor internationally. Anyone familiar with Istanbul, or who has attended an art event there, might wonder how so many politically critical artistic voices find a place in the city’s stylish galleries and cultural venues. After all, nearly the entire cultural sector operates without government support and relies almost exclusively on private sponsorship. The fact that the religious-conservative state apparatus is becoming increasingly hostile towards the art scene—perceiving in them progressive worldviews that clash with its own conservative-moralistic leadership style—and demonizes artists as the cause and perpetrators of the anti-government protest movement, is leading to an even sharper politicization of the entire art and culture industry. Of course, this divide stems from a complex interplay of ethnic, religious, political, sociological, and cultural factors, which only become clear with sufficient understanding of the country’s history. VERSION invited me to write about Istanbul’s art and cultural landscape, exploring its complex entanglements with differing worldviews and shed light on their backgrounds.

My starting point is a relatively recent political event—without delving too deeply into chronology—the so-called Gezi Park Uprising of May 2013. It remains one of the most significant events in modern Turkish society, continuing to reverberate politically to this day, an event that deeply divided society, but also presented the greatest opportunity for change, unity, and mutual understanding. For artists and cultural practitioners, Gezi is a central issue and field of inquiry. Since then, the scene has remained in a constant state of mutation—analyzing and processing what happened and translating that experience into both artistic and activist-political practice. Tactical thinking, market-critical strategies, network formation, new cooperative models, critical consumer behavior, and process-based interventions have all been debated, documented, and developed in forums and networks that emerged during and after Gezi. “Everything that was must be rethought and questioned.” Because even during Gezi it was said: “Nothing will ever be the same again.” Theory and practice collided, and every participant learned their lesson. Standing together in the same space against injustice—free of ethnic, gender, social, or religious prejudice—simply as individuals, sharing, supporting, building barricades shoulder to shoulder when needed, speaking out and listening to one another, working and singing together: All of this led to a huge mental and social leap forward. Against a bureaucratic neoconservatism, the demonstrators expressed their own political wishes on the streets—not only against state power, the police, the government, the family, tradition, language, the school system, the centralized bureaucracy of political parties, macho masculinity, and hetero-dominance, but in favor of something fundamentally different. “The revolution winked at us!” was scrawled on a wall.

And now, not only the younger generation, but even older generations— who had gone through other political processes, had defined their experiences, political opinions and world views in certain categories—feel a distinct “before” and “after” Gezi. It was not just a protest against injustice and state/police violence; it sparked a collective awakening to self-analysis and self-criticism. And the very generation that has been accused of absolute depoliticization is now pulling on the reins of the country’s largest protest movement in decades. Gezi was not merely a symbolic act of protest, but a struggle that necessitated the abandonment of party politics, worn-out clichés, and binary oppositions. It was the beginning of a new process of political thinking and action—whose course has yet to be defined.

Conceptualization in advance: Paratactic Commons

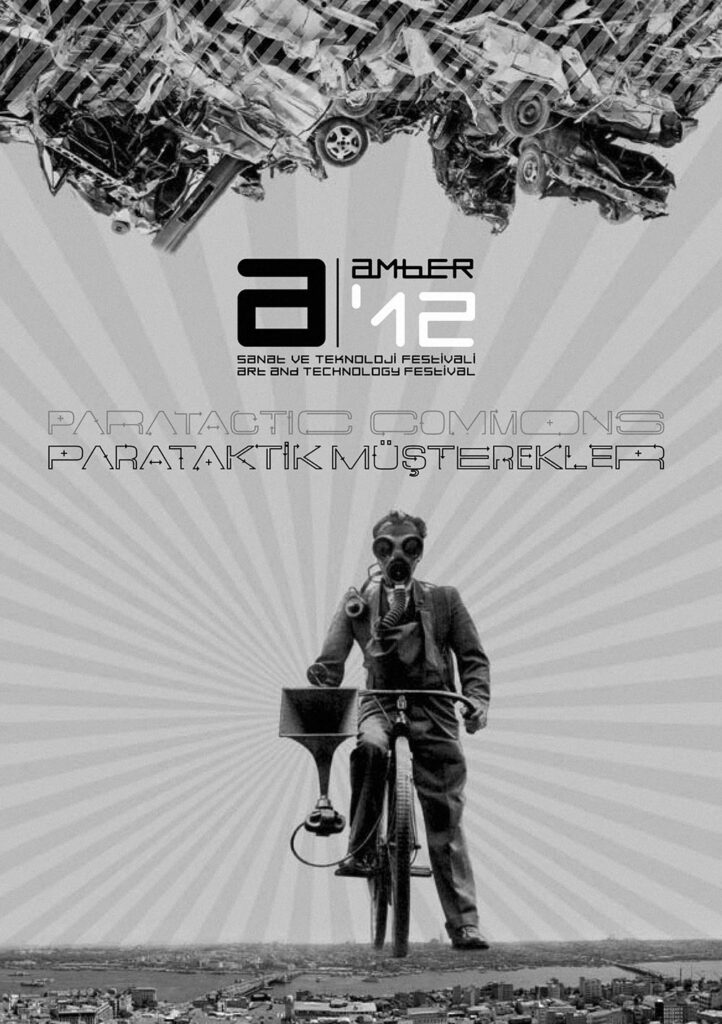

In 2012—around a year before Gezi—we developed the theme Paratactic Commons3 for the Istanbul-based media art festival amber.2 At the time, we could hardly imagine that our theoretical explorations would so soon gain urgent political relevance with the eruption of the Gezi uprising. What we put up for discussion with the term “paratactic commons” was simply to pursue the question what alternative economic, ecological, and political models of living, production, and communication exist outside of dominant systems? Could they allow us to break free from our increasingly monitored and controlled lives, to regain our democratically and politically justified rights of social co-determination, and finally to no longer serve the consumer machinery as target profiles, trapped in existing networks? We specifically asked: what can we learn from P2P systems, Copyleft, Creative Commons, free software, open source/open knowledge movements, or critical engineering approaches? How can we transform our hard-earned knowledge into a new artistic practice—one that allows for different modes of articulation and argumentation, beyond the art market and existing networks, without succumbing to normative limitations imposed by hyper-connected, controlled systems? Which paratactic configurations could enable effective and indispensable cultural counterpoints, so that artistic practice, in embracing diverse resources—identity, class, locality, gender, generation, ethnicity and other—can reconnect with social movements and fields of local and global critique? Artistic practice, in this sense, must not operate from the outside or the margins as a privileged observer commenting, criticizing or questioning on politics. Rather, it must confront and engage the political and social conditions of contemporary art practice, i.e. the institutional structure of liberal-democratic-capitalist societies and their dictates, conservatisms, and nationalisms. In hindsight, many of the questions were directly confronted during the Gezi uprising, when the realm of art in which we operate was effectively dissolved into lived political experience.

Even before Gezi, one amber’12 project had already engaged with the city’s exploitation of public resources for economic gain: Mapping the Commons of Istanbul.4 This was a 7-day workshop led by Pablo de Soto (hackitectura.net) and Daphne Dragona (media art curator, Athens/Berlin) in collaboration with Aslıhan Şenel, Demitri Delinikolas, and José Pérez De Lama. The team studied, analyzed, and visualized problematic zones of gentrification in a city overwhelmed by construction. One of the six areas investigated by workshop participants was Taksim / Gezi Park, as redevelopment plans were already under discussion.5 The results were later presented at the amberConference and discussed with other participants—topics included commons, public space lost under the privatization pressure of the state apparatus, power and control, ecological and economic alternatives, and on the right of access to knowledge, resources and distribution. While these discussions took place, just 500 meters away, Taksim Square was being transformed into a massive construction site by the city government—without any public announcement. The first isolated protests had already begun. Even at that early stage, activists saw the need for a united platform to defend the city’s shrinking green space. From this, the Taksim Solidarity platform emerged—a coalition of civil society organizations and professional associations that served as both an internal communication channel and an external voice during the Gezi protests. When the police violently cleared the Gezi Park occupation—using tear gas, water cannons, chemicals, and rubber bullets—a wave of protests swept the country. The government’s construction project, including the Ottoman barracks (i.e. the shopping center), was stopped for the time being by the demonstrations and ultimately declared void and illegal by Turkey’s highest court.

Penguins in the Media / Battles in the Streets: The Revolution Will Not Be Televised!

As we all know, the media determine our public spheres. With the erosion of “public space” as a politically meaningful site—once central to for the democratic reproduction of an enlightened, transparent society—mass media stepped into that role, endlessly producing and disseminating opinions while reducing the public to mere spectators. What we are sold as “public opinion” is really just published opinions and do not represent the public. Under the control of dominant powers, the masses are led to believe that the media always tell us the truth Basically nothing new and very simple, but it works everywhere.

During the evacuation of Gezi Park and the most brutal episodes of police violence on the streets of dozens of cities across the country, the government-controlled mainstream media chose silence. Already in recent years the crackdown on opposition media had already intensified. The government explicitly demanded that coverage of the demonstrations cease—and the media complied. Despite this media blackout, more and more people poured into the streets. Many critical journalists were fired for refusing to ignore the nationwide uprising. Charges were brought against numerous members of the press. The few newspapers that dared report on the mass protests were branded as traitors to the country by the government. While Turkish media ignored the largest protests in the history of the Republic and instead aired documentaries about penguins, citizens had to rely on foreign media, the internet, and social networks to follow what was happening. Through self-organized livestreams, blogs, and online forums, a form of citizen journalism emerged—making it clear just how essential active participation in alternative media had become.

The Nature and Language of Protest: (Passive) Fighting as a Creative Act

One of the most striking tools of Gezi’s defense strategies was the use of sharp, ironic language in graffiti, banners, slogans, and all kinds of written media. Negative statements by the government or pro-government media were turned on their head and thrown back with critical distance. Though city workers repeatedly painted over these slogans with gray paint, citizens responded by brightly painting public staircases, turning the color gray into a symbol of state repression. Well, I must mention here that the country has a very long humorous tradition in which the ironic use of language has been used as a defining element of discourse in many contexts.

Slogans like „Where are you, my love? Here I am, my love!“ and „Leg to shoulder against fascism!“—both statements from Turkish LGBT activists show the subtle humor and (self-)criticism of a left-wing use of language. The Lesbian-Gay-Trans-Bi-community had been fighting for years against homophobia and hatred; in the two years prior to Gezi, more than ten queer individuals were murdered across the country. During the uprising, they stepped into the spotlight, describing their newfound visibility with the words: “For the first time, we feel like normal people, part of this society.” Gezi was a unique and extraordinary experience. We saw a Kurdish activist and a Turkish nationalist resisting hand in hand, or an almost 70-year-old woman with a slingshot fighting on the front line against the police’s plastic bullets. Mothers staged massive protests in response to a government call urging parents to come pick up their children from the park. They came, indeed—but to demonstrate. They shouted at the police: “The mothers are here—where is the government?” Women threw themselves in front of chemically laced water cannons to stop them. Elderly aunts brought home-cooked meals to the park to nourish the demonstrators. People opened their doors to those fleeing the police, hiding them in their homes. Volunteer doctors treated the wounded in the streets at the risk of losing their jobs—or their freedom. Pharmacies stayed open late to help. Weddings were held in the park. Atheists joined Ramadan fast-breaking ceremonies out of respect for religious allies. […] This overwhelming solidarity—combined with humor, a sense of justice, and creativity—allowed people to overcome even the fear of death. Suddenly, everything seemed imaginable as one banner in the park proclaimed: „Another life is possible.“

Where Does Art Stand? What Can It Fix?

A geographical (scene-designating) place (in this case Istanbul) tends to be thematized and treated, read or received categorically as something homogeneous, total or uniform. In 2005, for the exhibition Der Knochen der Zunge6 (at the Medienturm Graz, as part of the Diagonale with artists from Turkey), I wrote the following to describe the dynamics of the local Turkish art scene: „[…] An art practice that operates with its own criteria and frameworks is not necessarily interested in creating lasting (museal) values, but very much in developing an independent aesthetic of communication. […] The field of preferred operative terms contain social orders in the form of meanings, practices and beliefs—everyday knowledge about how things function within this culture, the hierarchy of power and interest, and the structures of legitimacy, limitation, and boundaries. The selected signs refer via their codes to the orders of social life, to economic and political power, and to ideology, making them legible […].“ If I may reinterpret this in the context of Gezi, two aspects stand out: the creative process itself, and the aesthetic of communication. In our own artistic work, we often begin with a question and go through a self-guided process to arrive at an artistic result—and that process profoundly shapes the final work. In the case of Gezi, this process was not based on a hypothesis or theory, but came directly from reality, which one experienced with full force on one’s own body. The key point is that the process itself becomes important and develops its own aesthetic in direct practice: Art becomes life and life itself becomes creative and artistic. Many artists and cultural practitioners were involved in the park; although they were not the only promoters of this creative process, they were often the impulse generators. In the spontaneous chaos (sometimes out of sheer desperation), many art-like actions and gestures emerged. Among the most iconic was “the standing man” in Istanbul—and simultaneously “the standing woman” in Ankara. These individuals stood silently and motionless in central squares for nearly eight hours just after the violent evacuation of the park. When the images went viral, hundreds of people around the world replicated the act. These and many other interventions raised a critical question: Is it even possible to make art after Gezi? In fact, the art business was more or less shut down by the operators themselves during Gezi. Even the Istanbul Biennial, which was conceived as art in public spaces, had to retreat into art spaces in the end in order to remain attractive to the international art public.

Final Statement: „This is Only the Beginning“

The fight against conservatism, paternalism, autocracy, and environmental destruction in the name of power and profit continues on all fronts—even if the word „fight“ may sound harsh. What Gezi set in motion was not just a local phenomenon—it had global significance. Even if the framework conditions and political circumstances are country-specific, individual problem areas are the same worldwide. We saw this in the simultaneous uprisings in Brazil, Bulgaria, the Philippines, and beyond. „This is only the beginning. The struggle will continue.“ This Gezi slogan continues to resonate—at every football match in the 34th minute (34 is Istanbul’s license plate code), during the latest corruption scandals, and with every police raid. Many people were awakened on Taksim Square7 and the effects seem to last for months afterwards.

Postscript: „Taksim is Everywhere“ / „Down with Certain Things!“

What comes next won’t replace what came before—it will expand it. Certainly, many things change in form and articulation or in the sharpness of the language. Art is just one of many ways to pose questions and resist authoritarianism and the corruption of power. Admittedly, there is a certain pessimism in the minds of many politically engaged people, not least because of the recent state scandals, where the details of the internal machinations of the so-called “deep or parallel state” are gradually becoming known.

In an online interview with disillusioned activists, political theorist Michael Hardt responded: „I still trust in the people—even if they are no longer occupying Taksim Square or marching in the streets. I trust that those who are critical will return. I can even say with certainty that they will come back. What seems lost or fragmented right now still exists, and it will find expression again in another form. I don’t yet know what form that will take. Like you, I’m not just interested in a change of government or leadership, but in deep social transformation and that was, at the very least, one of the most inspiring elements of the Gezi uprising in the summer of 2013. We all agree: social change is a lengthy process and that can make us a little desperate over time, as we are living in the present. […]

It may happen long after we’re gone. But these fundamental social changes—that’s what we’re truly invested in. And they don’t happen overnight. Sometimes, they take unexpected detours. They may even challenge our deepest visions of society […].“8

The future will tell whether he is right in his thesis, or to what extent such changes will be possible in societies at large. One thing, however, is already clear to me: this process has undeniably already begun—at least among artists and cultural practitioners—and we can continue to expect compelling and thought-provoking art projects emerging from this part of the world.

1The wave of protests around Gezi Park began on May 28, 2013, in Istanbul, sparked by demonstrations against a planned construction project of the Ottoman barracks on the grounds of Gezi Park, located adjacent to Taksim Square. After a violent police crackdown on May 31, 2013, the protests escalated. Demonstrators in several major Turkish cities opposed the increasingly authoritarian policies of the ruling Islamic-conservative AKP party. By June 2013, solidarity from Turkish diaspora communities around the world gave the movement a transnational character. Gezi Park became a powerful symbol of civil resistance against government repression and excessive police force. It was forcibly cleared by police on June 15. A central feature of the protest—often referred to as „Occupy Gezi“—was the occupation of Taksim Square, where intense confrontations with police took place. Turkish mainstream media initially ignored the protests entirely. The entire flow of information occurred through so-called citizen journalism channels, including live streams and social media platforms. In addition to Istanbul, Ankara became a major protest site with frequent violent clashes between protesters and police. In the multiethnic province of Hatay, near the Syrian border—particularly in Antakya-Armutlu—protests continued even during the normally quieter month of August. Tensions there remained high, and violence escalated again in early September. According to official information, during the first three months of the protests, more than 3.5 million people participated in around 5,000 protest actions. In the first 23 days, demonstrations occurred in 77 cities, resulting in 6 deaths, over 8,000 injuries, and around 3,500 arrests. More information: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proteste_in_der_Tu%CC%88rkei_2013

2Concept by Fatih Aydogdu and Ekmel Ertan. More info http://www.amberplatform.org

3Festival publication (PDF): https://de.scribd.com/document/157454705/amber-12-Art-and-Technology-Festival

4Mapping the Commons of Istanbul project website: mappingthecommons.net/istanbul

5Project videos from Mapping the Commons of Istanbul: meipi.org/istanbul

6Exhibition press release: Der Knochen der Zunge (2005, Graz Medienturm, part of Diagonale):

http://2005.diagonale.at/releases/de/uploads/pressetexte/presseinfo_der_knochen_der_zunge.pdf

7Reference to the song “Kiss at Taksim Square” by China Woman:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=utLwKVmU2FM

8Interview with Michael Hardt, translated from Turkish into German by the author (Dec 21, 2013):

http://www.demokrathaber.net/roportajlar/m-hardt-eminim-ki-gezi-eylemcileri-geri-donecekler-h26207.html