Interview / Melanie Ohnemus, Philipp Furtenbach / Version 2

On the State of Things

Philipp Furtenbach of AO& in conversation with Melanie Ohnemus

The conversation took place in the AO& storage space, located in the basement of bookstore 777 on Domgasse, 1010 Vienna.

How important are gathering places for you? Much of your work seems to be about bringing people together— and, in particular, very different people.

That’s been a central element since the beginning of our collaboration—and still is. We like gatherings where barrier-free, cross-class communication is possible. With the strategies we’ve developed over the years, we try to create situations that are specific and defined, yet open enough to bring together people who might never otherwise meet.

What kind of strategies do you use to realize that concept?

Often it involves using a unifying dramaturgical device. You create a kind of barrier—or better, a bottleneck—through which guests or the audience must initially pass. That situation naturally forms an informal unity among people arriving from different backgrounds and emotional states. Sometimes we even make it a bit difficult on purpose, cause a sense of alienation, but then signal very clearly and in unconventional ways that everything necessary is in place to feel comfortable and stay for a while.

And doesn’t have to die? [This is also a reference to the project Leben und Sterben in den Bergen, Großes Walsertal, September 2008.]

Exactly.

In the beginning, food played a much bigger role in your work. Later on, it was sometimes included, sometimes not. What led to that shift?

Various other aspects became more important, and then it actually ended with a conscious decision. After the third work in the Großes Walsertal, we decided to stop cooking for an indefinite period of time.

But you’re not trying to unsettle people—your aim is more about breaking codes, especially those that are fixed laws in the cultural sector.

Not just in the cultural sector—also in everyday life. In some cases, it happens by itself. Like when you get stuck in an elevator with someone or the train breaks down and suddenly people start talking to each other. After all, this is shared potential suffering that connects people. The idea of such situations is consciously used in our work.

Speaking of shared potential suffering—would you say your work often revolves around basic needs?

When talking about “shared potential suffering”, it also makes me think that your work is very much about basic needs. Is that true?

Eating, sleeping, dying, surviving—yes. It’s also about the fundamentals of material. For instance, in the Principal Concerns series (2012), we manually extracted or produced industrial quantities of coal, salt, fat, sugar, and alcohol. It was important for us to physically experience those processes. That series marked the end of our first phase, when food played a more central role. It was always about raw materials, their places of origin, and the social structures around their production.

That sense of traceability was essential to us and led to a core principle: only using ingredients from sources and producers we personally knew. Food as a collection of places, which it actually always is, only that we have pursued this consciously and orthodoxly. Food is very well suited to weaving together complex relationships in a coherent way, in the procurement of ingredients, in the kitchen, on the plate and within the sequence of dishes on a menu. You can make far-reaching connections tangible and create coherence within a very limited spatial and temporal framework. These are conceptual finger exercises.

For our Peasants‘ War cycle (since 2013), we meet with farmers, many of whom we know from previous projects, for audio interviews. These conversations remain anonymous, the voice is alienated. We explore the farmers’ psychology and self-perception in relation to their political situation. We are interested in how much it would take for them to “stand up” and actually join the Peasants‘ War. In the past, farmer uprisings were common. We navigate through these conversations with very direct questions and always ask them for an object that can be turned into a weapon in no time at all. This project will continue for another one to two years and become a collection—of testimonies and weapons.

Looking back at your projects, where do you stand now—inside or outside the art world?

Both. For a long time now. We like doing things that function outside of classification. It never really mattered to us what segment we were placed in. Still, the art context allows for more freedom to take certain stances and to realize things. Art also offers protection.

Our work follows an internal logic—it evolves from a chain of interconnections we’ve been exploring for years. It started with food and the places food comes from. Over time, the social dynamics and the site of each work became more significant. The places have become more extraordinary or are being turned into something extraordinary by us. These settings aren’t found in everyday life. They can host or enable various processes. Music performances and recordings have also been taking place for a year now. These arrangements and dramaturgies emerged from looking back and analyzing the spaces we’ve created in recent years. In part, it is now much more abstract, as we have probably simply abbreviated many things as in a fractional calculation. In the case of concepts with music, the performance is combined with installative, spatial interventions to create a social event. In the collaborations with the musician Phillip Sollmann, we convened assemblies (Assembly 1, Villa Massimo, Rome 2012 and Assembly 2, Kunstraum München, Munich 2013). Spatially, the people found themselves in council or negotiation situations, sitting opposite each other and left alone in rooms filled with Sollmann’s microtonal drone music. The environment was stimulus-free, the performer was not visible and there was nothing to discuss. The simultaneous experience of isolation and coexistence created a neutral devotion and silence that lasted for a long time.

As part of the Performative Screenings series at school, Vienna (2013), we recorded the percussionist Didi Kern in a three-day, two-floor arrangement. In Request for Fire (2013), Nikolaus Gohm’s entire studio was moved into a 30-meter-deep cave for a public recording session.

There was also an equally public recording situation during the hike, which led from the city center to a house without windows and doors, which stands in a clearing in the Wienerwald (Wer den Mund aufmacht, Kunstraum Niederösterreich, Vienna 2013). Walking creates a kind of communication that simply doesn’t happen around a table. The hike ended in a choral performance, followed by an overnight stay in the woods—and so on…

How would you describe the difference between a food-based and a music-based project? What experiences have you had here with different timing and frames in terms of the degree of abstraction?

The mode of participation is different. Above all, in a musical performance the audience is more or less in the role of spectator or listener, whereas in a meal it is also an actor. The guests then not only consume, but also actually do something. If, for example, the performer is “invisible” or not present, the audience loses its role as an audience, it then becomes a group of people who are in one place and come together. This is an exciting situation for us—we see these arrangements as experiments, as “friendly attempts”.

Do these concepts extend from things you personally enjoy?

That doesn’t necessarily have anything to do with it. There are certainly situations we create where we’d like to be ourselves. On the other hand, we probably wouldn’t attend some of our own events ourselves. Maybe because we’re aware of how much direction and control we’re exerting. But we think that’s often welcome and even necessary.

You’re actually quite strict artists …

Yes, we are strict. Formal strictness – that can definitely be affirmed, quite clearly. We set very clear framework conditions for the parameters of the social situation.

What does that strictness achieve?

We use these means to break forms of behavior so that new situations can arise between people. When it works. There are also people who feel quite offended, and our concept can certainly overshoot the mark. But this is collateral effect that we accept so that everyone is aware that we have a clear idea of what we are proposing to the guests and the social situation. Such concepts are often also about breaking through conventions that we don’t want to accept.

This means that there are strictness and rules, but also freedom to adapt to the respective situation.

The strictness sets the framework—within that, anything can happen. Strictness is just like the edge of the sandbox. The goal isn’t strictness for its own sake—it paradoxically enables more freedom. The apparent choice of many things is therefore generally called into question.

Last spring, we decided to make your storage space (the basement of bookstore 777 in Vienna) semi-public. Partly because of the path you have to take to get there—it’s in a forgotten alley in the 1st district, in a bookstore that is hard to categorize, and a way down into an almost claustrophobic situation, removed from everything that was and is outside. It’s our innermost core—all our images, drawings, photos, objects, even our old stove and coal sacks are stored here.

We use this seclusion to do portraits with artists and others (Portrait/Interview series at the 776 Lodge, Vienna, since April 2013). We conduct one-on-one interviews with the people we invite in private. These are very personal conversations that we record. The audio recordings then remain under lock and key for ten years. That creates an astonishingly open, intimate conversation. Afterwards, the public part begins: waiting guests can come downstairs to view the interviewee’s exhibited works. The cellar room holds 15-20 people, who all write their names on a sheet of paper that is laid out for each evening, without knowing the purpose of this process. We are not interested in the email address or anything like that, we are more interested in “forcing” a commitment to be present there. It breaks the norm of simply just to be there somehow, and unites people in an abstract way. This also has an impact on their behavior, and not to their disadvantage. We don’t think we’re taking anything away from them except their name on the paper, but it sometimes changes the way they move.

Every person falls back on more or less conscious patterns when entering into such and similar occasions. The dramaturgies are predetermined by museums and galleries, because these are non-binding places for social encounters. But here you can’t just drift through as a detached observer. You have to be present—pass through the ritual of giving your name. And in the same breath, you’re offered a schnapps—everyone is. You don’t just give—you also receive. Symbolically. We take it seriously. We often see ourselves as guardians—guardians of spatial-social integrity. Individuality absolutely has its place within that.

AO& certainly radiates integrity. Is there a well-meaning, pedagogical side to that?

You have to be careful that it doesn’t get too serious, too gravitational. Humor is important. We also have to laugh a lot.

Is that also why you’re cautious about releasing photos of your projects? After all, photos in particular create a fragmentary image that is often in no way related to the experience itself. How do you deal with the documentation of your work?

Our work is well-documented and some images go beyond documentation. There’s a lot of information collected, and that has value for us—but it plays a subordinate role at the moment. On www.aound.net of the social situations discussed you’ll only find pictures of empty spaces—no people. We do not want to and cannot present or convey this life in a condensed form of information. You have to be there.

Tell us about your current project—The Hotel.

Next year, we’ll be managing a large hotel for a limited time. It’s in Bad Kleinkirchheim, a well-known tourist area, as part of a series of art projects exploring what Land Art could mean today.

For us, the first question was: What do we actually do in a public art project like this? The motivation for the project itself actually comes from tourism.

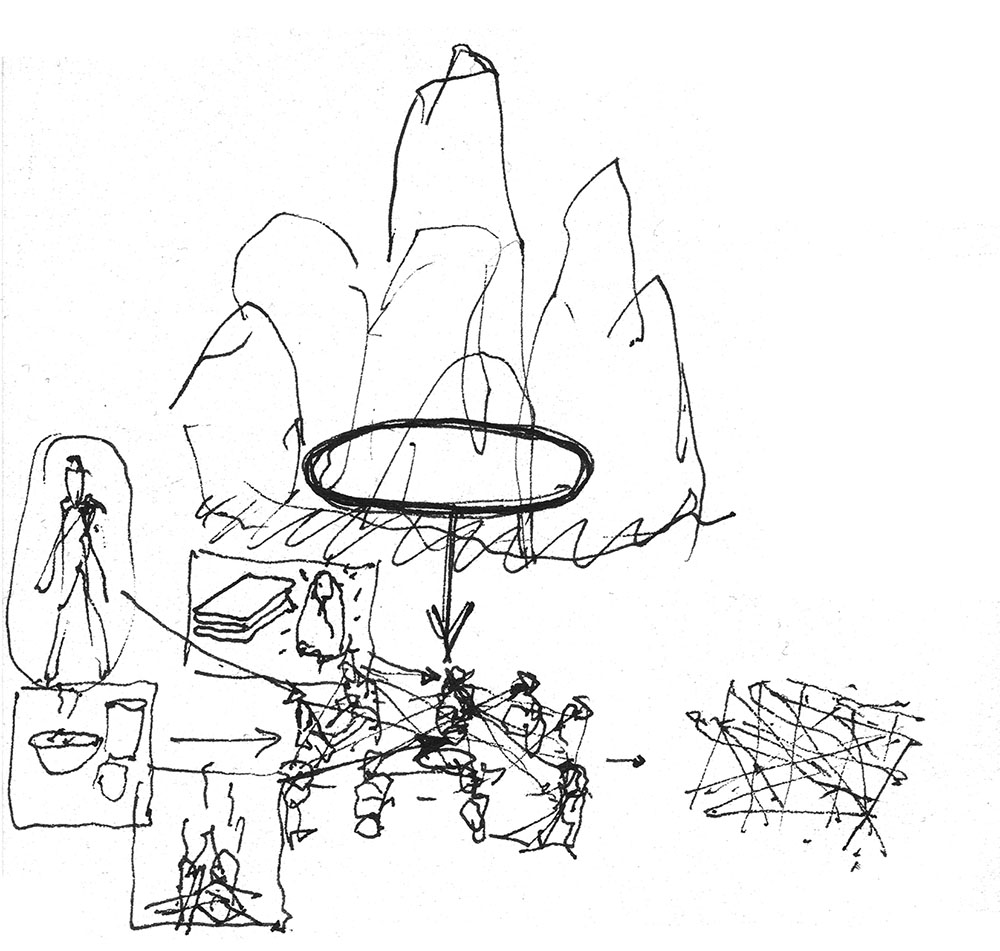

It takes place in a tourist region, in a place that was still a farming village in the 1930s and was later renamed from Kleinkirchheim to Bad Kleinkirchheim. Incidentally, this was one of the first marketing measures. In its heyday, there were 8,000 beds, but occupancy has been declining for years because such places are apparently no longer as popular as they used to be. And so, every few years, those responsible for tourism try to bring the whole thing back to life with new concepts. Now they want to try their hand at art. Fortunately, they then came across Edelbert Köb to curate the project, and he invited us to create a Land Art-scale statement. During the site visit, we wondered what this could actually mean and wanted to leave immediately because it seemed absurd to us. You then ask yourself whether you are just being instrumentalized as an artist, or whether there are justifiable options after all. The landscape there has been abused by all the cultural activities (agriculture, ski lifts, hiking trails, etc.) and we didn’t really want to add anything else.

But in the end, we chose the biggest and ugliest (supposedly ugliest, it’s actually the most beautiful) hotel and declared it an object. The organizers on site prefer to have large objects so that they can show something—we thought: You want a large property? This is it, and we are now running it under the new name Hotel Konkurrenz.

How long will you run it?

Thirty days—from mid-May to mid-June 2014. However, the whole process has already started with the fact that we were able to persuade the owners and managers of the existing Hotel St. Oswald to hand over their building to us completely. We are dealing with the spatial situations, will intervene quite heavily and will also carry out modifications to change processes and create new settings within the hotel. In some places, we expose the load-bearing reinforced concrete structure and thus make the organization of the design-forming layers visible. The most far-reaching changes are made by reconfiguring the interior.

The social situation on site also plays a role, the owners, the current employees and their current clientele. We have already spent a few days at the hotel and have worked in various positions. To show respect, but above all because it’s the most efficient way to get to know the people. We will need a total of around 30 people to run this 100-bed hotel. Half of them will be employees from the existing hotel, whom we want to recruit for the project. The other part will be people that we will bring along ourselves, including a few professionals, such as cooks, for example; we see everyone else more from a performance perspective. You can see the structure as a kind of theater and understand it as a sequence of spaces within which different figures with different functions or needs move.

In other words, we not only consider what it takes to run a hotel in practice, we want to question the unwritten premises according to which such a hotel business functions today, and the ideas of what the guest expects or needs, or also of what you think you need in order to be competitive.

We’re excited to create and operate this parallel world. The building is spacious and comfortable, and offers a variety of ways to pass the time, from the swimming pool, steam bath and sauna to tennis courts. There are various accommodation models for more than 100 people, allowing for a wide range of visitors. There will be an extensive program of contributions from artists, musicians and other guests throughout the entire period. A large machine will be created—the ultimate meeting place—where many people will get to know each other again.