Interview / Alexander Brodsky, Claudia Cavaller / Version 2

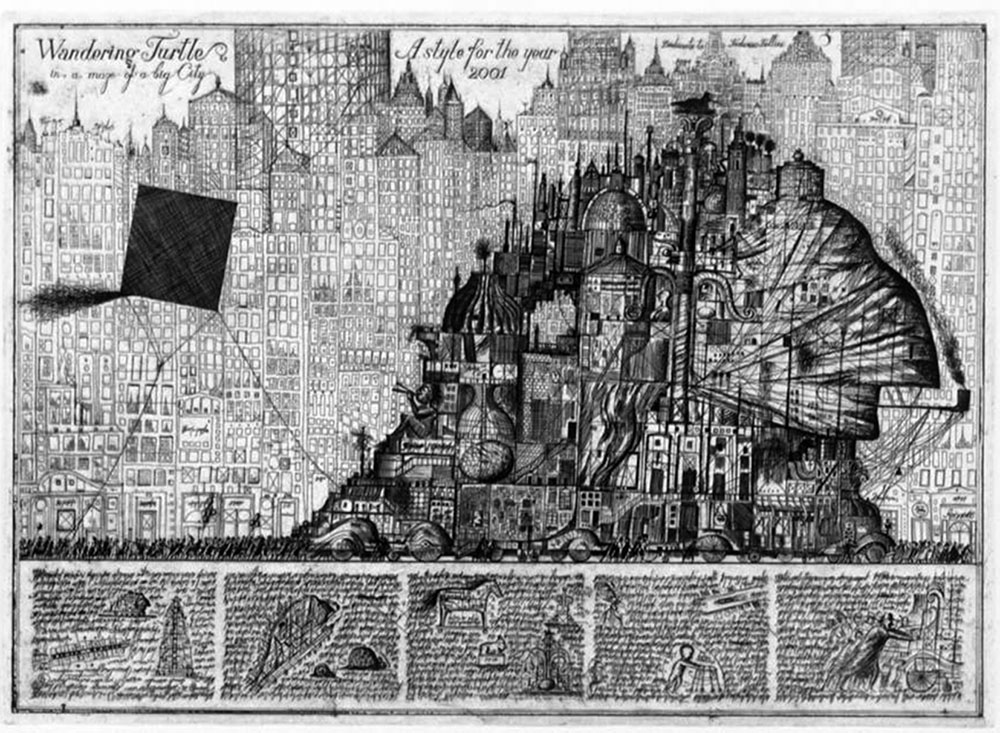

“To distract and soothe myself from my own failure, I drew ruins.” —Alexander Brodsky

Reflections on the Work of Alexander Brodsky by Claudia Cavallar, Manfred Grübl, and Linda Klösel

Alexander Brodsky was born in 1955 into a family of artists. He studied at the Moscow Art College and, in 1972, transferred to the Moscow Institute of Architecture. Together with Ilya Utkin, he became part of the Russian Paper Architects movement. Their utopian and fantastic designs sought ways out of the dreariness of architecture in the Khrushchev era and the period of stagnation under Brezhnev. In the 1990s, Brodsky focused on his artistic practice through drawings, sculptures, and installations, moved to New York in 1996, and gradually established himself in the art world. In 2000, back in Moscow, he founded his architecture studio and began designing restaurants, single-family homes, and temporary architectural installations.

C.C.: I find the pavilions at the Pirogovo resort fascinating as places for everyday rituals that we stereotypically associate with Russia—like drinking vodka or going to the sauna—because Brodsky draws on traditions of the Russian dacha. Some of his works are really beautiful, almost painterly, like the Vodka Pavilion with its old windows. Why did you choose him for this newspaper feature?

M.G.: Initially, we were interested in his ecological approach, his focus on recycling in architecture, and the rawness of the materials. His work clearly deals with impermanence and the extent to which something can be reabsorbed into a cycle. The paint on the Vodka Pavilion is already peeling. This is precisely what is usually avoided in architecture. The potential for decay is generally prevented. Corten steel may rust, but there must be no traces of rust when exposed to the weather. There are similar phenomena in our everyday lives. Products are made that no longer contain what they claim to—coffee without caffeine, beer without alcohol, and so on.

C.C.: But Brodsky’s kind of recycling carries a patina that actually means something—it holds memory and references something else. What you mean is probably even more true in Russia than here. Everything has to look new and as prestigious as possible. There’s this tendency for everything to appear seamless, like it all fits into some idea of “good taste.”

L.K.: Their fractured nature gives the pavilions a strong sense of individuality—they’re not interchangeable or replicable.

C.C.: Exactly. When I have materials—like those old windows—the question becomes what can I make with them, not the other way around. If I need old windows because the concept demands it, then things get tricky. I think Lacaton & Vassal take a similar approach in that sense, though their work is more complex. They often use undervalued, off-the-shelf materials from the hardware store—again, the principle of using what’s already there. That gives their work a distinct aesthetic, one that is based on architectural elements. In this way, they create their own kind of freedom. There is a beautiful article by Lucius Burckhard that says something like, “maybe the future belongs to the collagists”—people who take what’s mass-produced and create something personal from it, rather than believing they have to master a process from A to Z. Brodsky’s approach is more romantic, I think, even if not all the materials are literal fragments of ruins—they’re often mixed with industrial or new components.

M.G.: He’s also always adapting to the specific context of the site, like with the Ice Pavilion, where a house with a grid is sprayed with water at sub-zero temperatures. In the broadest sense, the shell then becomes part of the landscape again.

C.C.: It reminds me a lot of projects from the ’90s, like those by The Poor Boys Enterprise. Spaces where something was staged—subversive interventions. Or the 95 Chairs by next ENTERprise-architects. The intent is to make a public statement, but in practice the use is often limited to a particular group.

M.G.: Brodsky’s work often revolves around specific events, like the Rotunda for the Archstoyanie art festival. In these temporary gatherings, there’s always the need for some kind of overview. An observation platform addresses that need—you can go up, down, around, look through window openings, and constantly get new perspectives on what’s happening and the environment.

C.C.: Projects like the 95° Restaurant look, in photos, like vernacular structures—improvised barns you might find along the Danube, something without parents. I was actually a little disappointed, because in reality, it’s all very precisely planned, and that kind of takes away the charm. The typology is there—like little garden pavilions [Salettl] or Russian dachas. But it’s not just that he uses certain materials; he also references this idea of „helping yourself “ with whatever’s at hand. If you look closely, you could say these are architectural quotations, thoughtfully applied, that aim to create low-threshold accessibility. That cozy, dacha-like feel—something familiar and casual, what you are familiar with because you do it yourself.

M.G.: There’s this phenomenon: when something is edge to edge and implemented very precisely and smoothly, nobody dares to use it. But if there’s a corner that looks messy or improvised, then everyone jumps on it and something can be created. Same with parties: no matter how big the apartment is, everyone ends up in the kitchen, because the kitchen is always a place where everything moves and chaos reigns. It reminds me of baroque landscape gardens—the ruins, the decay, the viewpoints that invite you to linger. When Brodsky gets into private housing, like the House on the 5th Green or the house for Marat Guelman, the concept kind of breaks down for me. That’s just pure postmodernism. Houses that already have a roof get another gabled one on top. These forms just reinforce and repeat existing ideas. Everything’s straight, orthogonal, easy to build. But I don’t get where that comes from—because from a craftsmanship point of view, it doesn’t matter whether I cut a board at a right angle or diagonally. In fact, if you try to cut one by hand at exactly 90 degrees, it usually ends up off. There’s also something about letting things happen and dealing with the results. In Mexico City, for instance, whole buildings are slowly sinking because the city is sinking into the lagoon. You find spaces where the floors sag by 5–10 centimeters, even in semi-public places like galleries. Here, they would tear it down immediately, but there they leave it, build even further, add pieces, etc.

C.C.: There are many ways to break the convention of the right angle. One possible path is the picturesque—and that’s the one Brodsky takes. The skewed, the ruinous… it all has something deeply poetic and spontaneous.

M.G.: Though it’s worth noting, with him it only ever affects the construction itself. Everything else is laid out orthogonally. Another thing I notice: when it comes to visionary thinking, Brodsky is always thinking about the city as such. At the turn of the millennium, these questions were posed in exactly the opposite way for us, namely whether the city still has any significance at all in an age of the Internet. In the ’90s, everyone thought cities would become obsolete as living and working spaces. But instead, we’re seeing a return to urban density. Although, the way we see cities has shifted—globalization turned the city into a kind of synapse, a network node where everything is simply transmitted. I don’t have to be tied to one city—I can be anywhere. The city is just a hub now. That’s how I interpret today’s concept of the city. But for a generation of architects like Brodsky—he’s not a digital native—it’s still about the city as a singular entity, about urban concepts and preservation.

C.C.: I can imagine that’s a reaction to specific Soviet-era planning policies. That kind of engagement with the city must have something to do with the fact that it was a place under constant threat of destruction well into the ’90s.

L.K.: What’s interesting about Brodsky is what happens in the space between art and architecture. He himself draws a very strict line between the two—Brodsky the artist and Brodsky the architect—which already raises a question about overlap and separation. The rough objects—like the pavilions—bring up issues that matter both artistically and architecturally. But those same issues get kind of relativized again when seen purely as art. Koma, for example, the clay city sinking in oil, has this intense, moral pathos that you don’t find in the pavilions. Memory and reflection are major themes, like in Grey Matter. He simply doesn’t succeed in saving the experimental, the open interplay of form and content, neither in what he himself calls art nor in what really constitutes living architecture, such as residential buildings.

C.C.: But I actually find a piece like Koma really compelling. It reminds me of Plötzlich diese Übersicht by Fischli and Weiss. He could’ve skipped the oil, sure, but formally I think it’s well done.

L.K.: Then there are artists like Rockenschaub, who have explored architectural questions in depth— like the Beethoven frieze in the Secession. Rockenschaub works very precisely with the space, also using color to direct the eye and movement. When architecture is viewed in the context of art, there are many ways to differentiate points of view. Brodsky turns his art into a kind of moral commentary on architecture. Like that piece in which he stages an archaeological excavation from antiquity under a grid with the remains of contemporary wars and consumer behavior does not, in my opinion, stand up to a contemporary view of art. What you’re left with is a closed narrative—a message meant to trigger reflection. And you can always sense a distinctly nostalgic philosophy of preservation in him.

M.G.: I also don’t get this sort of naïve approach. In the end, Koma is just an architectural model with windows and doors. He gets lost in details that, to me, feel totally unnecessary. In his architecture, he really holds back.

C.C.: To me it’s just not an architectural model, because he’s showing something an architect wouldn’t normally show—since it is usually about a planned project and not the plastic representation of a city The model feels almost like it’s from a fairy tale. This is always difficult for an architect, as he/she does not normally have the opportunity to question or undermine certain things like art does, because he/she is bound to a client.

M.G.: Really, all of Brodsky’s buildings are embedded in nature, standalone, never in cities. The restaurants are also always a dive into the basement. I wonder if it’s really about architecture—or more about nature. In the Ice Pavilion, the idea is basically just “ice.” Or in the Vodka Pavilion, painted white so it merges with the snowy landscape. Or the Cloud Café. It’s all very much oriented toward nature. And that, I find interesting. Integration into nature and how do I deal with nature? He uses what’s there—water, ice—they become the architecture. You get the feeling the trees he uses were felled right on site for constructions like the 95° Restaurant. The way the trunks are tilted, it feels like they were always there. Usually, everything is so industrialized—particle boards shipped in from China or wherever, everything is carted back and forth. Perhaps the most interesting aspect is that you work with what is available on site and thus create your own work.