Tina Leisch / Version 2

What a fucking shitty thing: To rest in peace!

Roque Dalton is El Salvador’s most important poet—and its most politically committed one. When he decided not only to invoke revolution with words but to fight for it with weapons in hand, he was prepared to look down the barrel of the gun of an illiterate campesino forcibly recruited as a soldier or a torture specialist trained by US instructors. Twice, Salvadoran military dictatorships sentenced him to death; twice, he escaped prison under almost fairytale-like circumstances and found refuge abroad. But in the end, it was a bullet fired from the pistol of a comrade—an illiterate of political thought from within his own ranks—that ended his life. That was on May 10, 1975, shortly before his 40th birthday.

The perpetrators are now known: The instigator was Edgar Alejandro Rivas Mira, who had studied in Tübingen, Germany. As head of the guerrilla group ERP (Ejército Revolucionario del Pueblo – People’s Revolutionary Army), his methods suggest he drew more inspiration from Germany’s Red Army Faction than from Che Guevara. Jorge Meléndez, the current Secretary of State for Civil Defense, can probably be considered a contributor. He imprisoned Dalton and his friend Armando Arteaga and ordered that they be guarded by young guerrillas under strict instructions not to speak with the prisoners. According to eyewitness accounts, Meléndez repeatedly entered Dalton’s room to beat him. Joaquin Villalobos, now an advisor to right-wing governments, is widely identified as the one who carried out the ERP leadership’s decision to execute Dalton. None of them has ever been prosecuted, none of them has ever asked the families of Dalton and Arteaga for forgiveness.

In researching our documentary film about Roque Dalton, we uncovered several motives behind the double murder of Dalton and Arteaga. One key reason was deep political disagreement: The Christian Socialist militarists Rivas Mira and Villalobos wanted a purely military resistance organization that would ally itself with progressive sections of the state army in order to seize power through a military coup from the left. The Marxist-Leninist revolutionary Dalton, who was trained in Cuba, insisted on political work, on organizing the workers and peasants, on building a revolutionary party and revolutionary resistance structures among the population. But the political dispute was inflamed by envy and jealousy. The younger, less experienced leaders resented Dalton’s charisma, his international stature, and his popularity. And to make matters worse, Dalton had taken Rivas Mira’s lover: the young poet and guerrillera Lil Milagro Ramírez.

To justify the murder to their comrades, the killers accused Dalton of being either a Cuban or CIA agent. ow the accusation of being a Cuban agent is not entirely far-fetched: Dalton and Rivas Mira met in Havana, and Dalton’s entry into the ERP had the approval of the Departamento de las Américas, which was responsible for supporting rebellious movements against the Latin American military dictatorships. So you could say that Dalton was a confidant of the Cubans within the ERP. To this day, no one understands what absurd logic could have been used to reproach him, given that the Cuban revolution was the great model for all Central American guerrillas and that it was the founders of the ERP themselves who had sought support in Cuba.

The charge that he was a CIA agent stemmed from Dalton’s autobiographical novel Armer kleiner Dichter, der ich war. In it, he describes being arrested in 1963 in El Salvador and interrogated by the CIA in a secret prison. They not only threatened him with death, but warned they’d defame him after killing him, branding him a traitor. An earthquake eventually cracked a wall in the prison, and Dalton managed to dig his way to freedom. An adventurous tale. Too far-fetched to be true, said his rivals. But now declassified CIA documents confirm that Dalton’s account of his interrogation was accurate—that he had, in fact, that he really did refuse to turn traitor to save his skin. It has now been proven that the accusations made by his murderers were false.

So the big, open question concerning Dalton’s death, which our movie couldn’t answer either, is: Were they really deluded revolutionaries who were so presumptuous and blinded as to kill the brightest head of the Salvadoran revolution out of envy, resentment and paranoia? Or was not one of the murderers a CIA agent who had the task of stirring up the conflict among the rebels until they murdered Dalton?

Was it ideologically stubborn Stalinists who could not stand Dalton’s sharp mind, his biting humor, his mockery that stopped at nothing and no one, neither the party nor the revolution and certainly not himself, his biting and pointed criticism and self-criticism? Or was it U.S. imperialism, whose greatest enemies are freethinking intellectuals who don’t just perform their outrage onstage or in print, but dare to challenge the empire as organizers of resistance and counter-power?

Morally, that question may be irrelevant. “Revolutionaries who kill to punish dissent are just as criminal as generals who kill to maintain injustice,” said Dalton’s friend, the Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano. But politically, the question is worth asking. In the 1980s, the USA spent three million dollars a day to prevent the Salvadoran insurgency movement from taking power as it did in Nicaragua. The police and military forces were equipped with the latest technology and trained in the most effective torture and espionage techniques. Is it imaginable that the US counterinsurgents even had a militarily successful guerrilla leader in their payroll? Was the ERP, which merged with four other groups in 1980 to form the FMLN (Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front), from the start a false flag operation— a pseudo-guerrilla force designed to sabotage the revolutionary movement under the leadership of a CIA agent?

Former ERP fighters reject this theory. They put their heads down and risked their lives. They attacked police stations, stormed military barracks, shot down helicopters. You ran the legendary guerrilla radio station Radio Venceremos. They were wounded in battle, tortured in captivity. They saw too many comrades fall fighting for a socialist El Salvador to believe they were led by an agent of the enemy. We keep hearing that this suspicion is just a convenient excuse to avoid the unpleasant confrontation with authoritarian, militaristic structures in their own ranks.

But as long as the right refuses to speak about the tens of thousands of murders and war crimes it committed during the civil war, few on the left are willing to talk about the hundreds of innocent people who died at the hands of self-important guerrilla commanders. Twenty years after the peace accords, El Salvador remains a country where the trauma of war is rarely discussed—at least not in the mass media. Not even the FMLN’s 2009 electoral victory changed that.

When Dalton’s sons—Juan José, a former guerrilla and journalist, and Jorge, a filmmaker—demanded the resignation of the Secretary of State for Civil Defense, Jorge Meléndez, from the first left-wing government, because no one suspected of murdering their father should sit in the country’s first left-wing government, they fell on deaf ears. Neither the party, nor the president, nor the public exerted any pressure on Meléndez to contribute to clarifying the case. On the contrary: he received anonymous support. In the fall of 2012, after a long investigation and a stroke of luck, we found former ERP fighters willing to speak on camera for the first time about the circumstances of Dalton’s murder. Shortly thereafter, our Salvadoran production manager began receiving anonymous phone calls warning her to stay away from the story— it would be dangerous to continue researching.

Roque Dalton himself would probably have laughed at the opportunistic careerists who killed him. “Forget these wretched creatures! Ask yourselves instead how the NSA uses the data it spies on! Do something about the computer game murderers sitting comfortably in the U.S., killing thousands of innocent people by drone—in Iraq, Afghanistan, Kurdistan—wherever a little more war means a little more profit.”

He might have said something like that. Only much, much better formulated.

Sources:

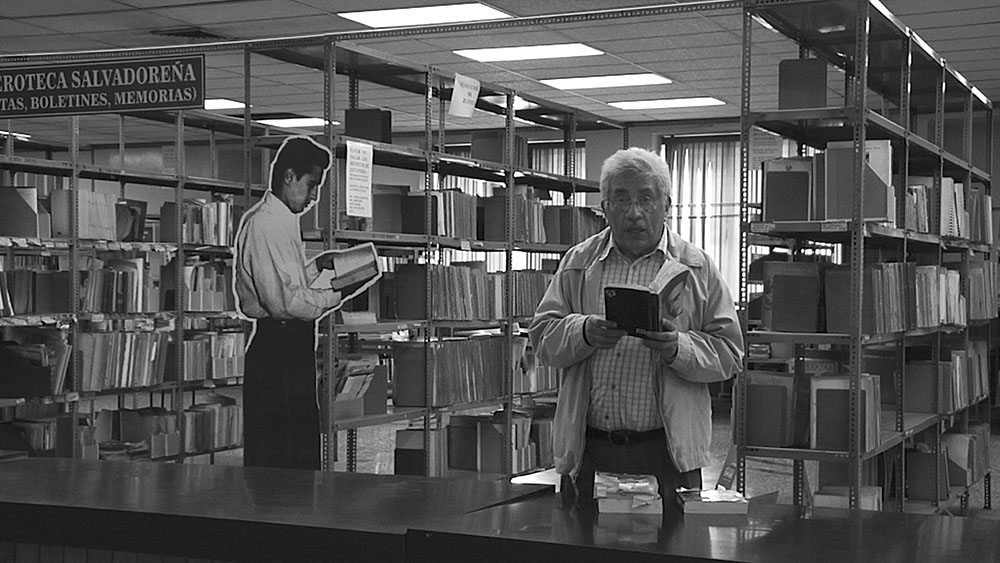

All images from Roque Dalton, erschießen wir die Nacht! / Documentary by Tina Leisch, co-developed with Erich Hackl / 2014

www.roquedalton.at

The Consolations of the Holy Sacraments I (1932)

Agustín Farabundo Martí

allowed the priest, to whom he had refused confession,

to embrace him,

and walked resolutely toward the wall.

Suddenly, he turned around

and called out to Chinto Castellanos,

the Secretary of State, who had kept him company all night,

talking and smoking cigars

in the chapel for the condemned.

“You hug me,” he whispered in his ear,

“it’d be disgusting if the last embrace I take from this life

were from some scheming priest.”

“And why me?” asked Chinto.

“Oh,” Farabundo replied, “because you’ll be one of us,

you’ll see.”

And then he stood before the firing squad that shot him.

II (1944)

To be able to shoot Víctor Manuel Marín,

they had to wedge wooden props

(the kind you use under an ironing board)

under his armpits.

During torture they had broken his legs,

his arms, and a few ribs,

gouged out one of his eyes,

and crushed his testicles.

The same priest who couldn’t get Farabundo to confess

approached Víctor Manuel and said:

“My son, I’ve come to strengthen your spirit.”

He replied, through broken teeth

and split lips:

“It’s my body that’s weak, not my spirit.”

Then they shot him.

III (1973)

Every time I look at the society pages

of the Diario de Hoy or the Prensa Gráfica

those luxurious obituaries

for two hundred colones or more,

announcing the death of a bourgeois,

accompanied by the Holy Sacraments

of our Catholic religion,

I think of what those two dead men tell us,

who refused such comfort and consolation.