Interview / Artur Zmijewsky

WE SIMPLY REACT / Jacek and Katarzyna Adamas talk to Artur Zmijewski

Artur Zmijewski

Start with the landfill.

Jacek Adamas

We came to Warmia for the first time in the ’90s. Kasia was nine months pregnant. And we had just arrived. For a week we lived in wild meadows, these were the times of fallen PGR (Public Agricultural Company). We were charmed, fields, incredible fields, with houses scattered every few kilometers. You walked sandy country roads with wild flowers just a few kilometers to the nearest shop. What a contrast to living in a city. And I needed a great change then. We looked for a hut for two years and finally we found this place – Worlawki.

A.Z.

You didn’t know then that the landfill was supposed to be three kilometers from here in a straight line?

J.A.

No, these decisions were made “semi-openly.” The landfill was supposed to be used by the whole voivodship (province), but officially it was maintained that only three parishes Dobre Miasto, Swiatki, and Ludomino would be using it. They said it was just a trifle, that nature would absorb it. Otherwise, nobody would have agreed to it, and that is how it started. Then, a protest committee was established by farmers in the village of Legno and we joined the protest.

A.Z.

Were the inhabitants asked for approval with regards to the landfill?

J.A.

Only the village administrators were asked, and they made the decision for us. This was illegal, a public consultation should have taken place, a local referendum. In the meantime, on paper, the village administrator agreed to the building of the landfill. We went to the administrator and asked how he could have decided about this kind of investment in this way, and we made a bit of a scene.

Katarzyna Adamas

Jacek undertook collecting signatures of those inhabitants of our village who were against building the landfill. He collected 30 signatures. Every fourth person signed, and there were some family conflicts because of that. In the end it appeared that most people were against it.

A.Z.

What happened next?

J.A.

We invited Mrs. Jaworowicz from the “Case for the Reporter” TV-program. That is when the conflict started with the parish mayor of Swiatki and leader of Warmia’s Association of Parishes who had not issued any estimate with regards to the effects of the landfill on the environment and people’s health. But we managed to find the report which said that the landfill would cause lots of harmful changes.

A.Z.

In what other ways did you protest?

J.A.

We are still fighting the legal battle. We support village administrators who are against the landfill and who organized the Lagno village protest committee. They collected about 1,000 signatures from surrounding villages. This is an army of people. This protest was also led by a local priest; it got to the point that the priest “excommunicated” the village administrator: he asked him not to come to church. The priest ran into some problems because the local Catholic authority said that he was meddling too much in politics. Anyway, the administrator couldn’t go to the local church because he had behaved disloyally towards the community, in supporting the landfill. It was a real, serious local war!

A.Z.

But you didn’t only protest using legal means there was also a gathering of heavy farm equipment on the terrain of the landfill.

J.A.

The protest has lasted a few years and we have succeeded in stopping the construction. People live in economic hardship here. They received donations from the EU to develop agro tourism in the area. This is indeed a great tourist region but the vision of the landfill and incinerators hung over it. So, we organized an association, “Let’s Love Warmia.” Members are local farmers, and we organized some events to become known. When supporters of the landfill, the president of Olsztyn, the prefect of the district, and the mayor of Swiatki wanted to meet “their” journalists and local TV, other journalists phoned us and told us what was being planned. This was supposed to be a very quiet meeting. There were pretzels, cake, and coffee. The idea was to get journalists who would write that the landfill was being built to make Warmia a cleaner place. And we arrived there with a group of farmers in tractors, informed the local TV, and there was a riot. It was no longer possible to organize a press conference where the authorities delivered their message with nobody asking questions about the sense of this investment.

A.Z.

What was the role of tractors in this situation?

J.A.

Tractors, such giants, were driven all over the ten hectares of this field where the landfill was supposed to be built. Some of them were with ploughs. They flew across these fields and later when they formed a line it looked like a scene from the film The Convoy with Chris Kristofferson. It made an impression. I screamed at the prefect: “If you want to fight, when the work on the fields ends, we will take this equipment to the streets of Olsztyn unless you leave.” It was on local TV. The President of Olsztyn was terrified.

A.Z.

Surely you are recognized as a local activist?

J.A.

Maybe. Ecological politics in the region is wrong. The characteristics of Warmia are forgotten houses scattered over the hills with various huts and barns. We hung banners all over the city: “Warmia without landfills.” We criticized the bad investments. Authorities get donations from the Union, for example. People transform farms to accommodate agro tourism while at the same time the officials are trying to get permission to build a landfill in the same place. Both programs are very well prepared but both annul each other.

K.A.

There is also a third program here, Nature 2000. Money from the EU is used to protect birds and their habitats. We think that EU officials do not control the flow of the money. There is no coordination because all of these initiatives annul each other.

J.A.

There is no economic argument for transporting rubbish 40 kilometers to the landfill. Especially when they say that it is completely harmless refuse. If so, why don’t they build a ski jump for Malysz out of it in Olsztyn? This is disinformation; there is no harmless refuse. Rubbish in a landfill is a danger. That is where bacterial mutations take place. One big boiling heap with temperatures of hundreds of degrees Celsius inside. A special gas installation has to be made. A stench spreads all over the area and stays in the lower parts of the terrain. And after a few years we will have a real stink here. This smell will be present in all agricultural products, for instance in the taste of milk.

K.A.

EU funds are not earned.

J.A.

They fall from the sky. You get them. They are not the effect of your development. There is a complete negligence of the stage of building an economic foundation, the feeling of possession, responsibility for the good which these funds could foster. It destroys any economic or cultural consciousness. We now have a period of illusion that everything is developing. There are notices in our parish that the new sewage system was built using EU money. But nobody had thought that the sewage would have to go to the wastewater treatment plant. On paper everything is fine. The sewage system works but the sewage-cleaning plant doesn’t because it is old and cannot clean this amount of sewage. In the end, the sewage-cleaning plant pollutes the Pasleka River.

A.Z.

And money was also received from the Union for the bird reserve, right?

J.A.

Yes, a sewage system was necessary. Its construction was financed by an EU allowance. Up until this time, not all houses in Swiatki parish had been connected to the system and nature somehow had coped, sewage had sunk in somewhere. Then the money came, all the houses were connected, the amount of sewage coming to the old wastewater plant rose, and now sewage flows into melioration rows.

K.A.

This is what happens with money which is not earned through work. The Union gives it to the local authority but does not control whether the financed programs are needed locally. Good program, convincing, let’s give the money.

A.Z.

Once again, we have four programs financed by the EU which annul each other in your parish: the birds and their habitats reservation, which is also the reservation of the Pasleka River; the development of agro tourism; the landfill for three voivodships; and the sewage system for the villages which transfers sewage to the old treatment plant which lets off this sewage into the legally protected Pasleka River.

J.A.

But when we want to prove it, we have to file for a water-cleanliness test of the water let off by the waste treatment plant, and we don’t have money for that.

A.Z.

Knowing you, surely you protested in the case of the sewage system?

J.A.

Yes, sewage from the treatment plant went all over the fields. Five hectares of fields flooded. It was a frightening sight.

A.Z.

It was classic sewage: feces, sewage, organic refuse, etc.?

J.A.

Yes, the whole field was flooded.

K.A.

From time to time, they make a “controlled let off.” It should be cleaned water. The case went to the prosecutor. The prosecutor decided it was an act of low social harm and had minimal impact on the environment. The case was dropped.

A.Z.

And what about the tests of the water which flooded the fields?

J.A.

The result depends on who performs the test. When a farmer ordered the test, paying himself, the result he got was that the water was dirty and he should get compensation. But when this water was tested at the Voivodship’s Inspectorate of Environmental Conservation, it turned out that this was first-class clean water. For a few years now, there has been a case against the former director of that Inspectorate, who had a heap of hospital refuse from Warsaw on his plot in Narajty. In connection with this case, I made a happening called Who will clean up Narajty?

A.Z.

Were there any art actions in response to the sewage flooding the fields?

J.A.

Action Clean hands. I spread white towels and bars of soap in front of the voivod’s office. I repeated it on local TVP 3 Olsztyn when I was invited to a meeting with the leader of Warmia’s Association of Parishes who is also the mayor of the village I live in. I formed an infinity sign. The protest was directed at the authorities’ inertia.

A.Z.

Tell me now, about your daughter Rose. She doesn’t speak; she should be going to the special needs school in Olsztyn. Transport should be provided by the parish. But something hadn’t worked out. That is when you threatened the voivod with a happening and she gave in under the threat of artistic action. How was it?

J.A.

Local officials do not care about ecology; don’t care about access to education. This is a system which shuffles the cards, destroys people. We keep relative independence and we protest.

K.A.

Rose is a special needs child. According to law, she should be going to the closest school, chosen according to her health and disposition.

A.Z.

And is this school in Olsztyn?

K.A.

Yes. The necessity of going to this particular school was confirmed by a doctor’s statement. We live 30 kilometers from Olsztyn. The parish is obliged by law to provide transport for such a child. On September 1, children from Worlawki went to the local school on a school bus. But nobody came for Rose. Of course, I had informed the mayor that there would be transport needed for Rose because she had been accepted to the special-needs school. And we waited patiently till September 20.

A.Z.

Are there more kids like this in the villages?

K.A.

Yes, quite a few.

A.Z.

The parish is obliged to provide transport to school for all children. But it doesn’t provide transport for the special-needs children and in doing so delays their start at school which deepens their problems.

K.A.

The parish does not want to take responsibility. These kids need a special curriculum. Every day out of school is a day lost. On September 20, there was a meeting of the parish council during which the officials (a farmer, plumber, and forester) were deciding if this school would be good for Rose. Later they concluded that there was no money for transport and that the parish could buy me a monthly bus pass and I could take Rose to school. The bus is at 5:45 in the morning and returns at 17:15 in the evening. That was when we went to the voivod and to the Education Council.

J.A.

We also accused the mayor of impeding us in carrying out our legal duty of sending our child to school.

A.Z.

Were you accused of not meeting your legal obligation as parents?

K.A.

No, the school knew the situation. We also spoke to directors of other schools explaining that there was a problem with the transport of the kids. We made it heard. There was TV here and radio, and they wrote about it in the press. It was a success because suddenly there was panic in the parishes, and the children started to get picked up. The director of the school in Olsztyn told us about it. But before that happened, we had had a problem.

J.A.

I was already strongly determined. We went to the voivod with Rose and I told her that on this day she would carry out her educational obligation in the voivod’s office.

K.A.

I brought some papers, pencils. Rose started to draw. Later she crawled under the table because she loves to look at shoes. She ate some sweets provided for official visitors and took the rest for the other children. Jacek said that it was her first day of school.

J.A.

And if there were no reaction we were going to arrange for a skip of sand to come and we would make a sandpit for the special-needs children in front of the voivod’s office.

K.A.

And straight away, the voivod dictated a note to the mayor concerning Rose’s transport. Soon we got a letter from the mayor saying that beginning October 19, a car would come to collect Rose. The mayor employed a driver and carer, and gave his car. It was a shock for people because the car in which the mayor usually drove around, started coming in the morning to the Adamas. Children were going to school by bus and Rose was going in the mayor’s car to Olsztyn.

A.Z.

And what was the prosecutor’s reply to your accusations?

J.A.

They refused to pursue the case because the mayor had started to fulfil his duties.

A.Z.

So the prosecutor’s office decided that if a child loses part of her school year, it is not a problem?

J.A.

There are different rules here. We met one vice prosecutor for the region and he told us, “Here, people don’t like newcomers from Warsaw and you don’t take the mayor to court.” Now we know that before someone opens a legal codex here, he checks to see if the person filing the case is from Warsaw. If so, they drop the case. For example, there was a case regarding the demolition of a nature reserve. The lead prosecutor for Olsztyn North assigned as prosecutor for the case a woman whose husband, mayor of Jonkowo Parish, was responsible for these harmful acts. Our letter to the court concerning the conflict of interest was ignored.

A.Z.

And do people fight for their rights?

J.A.

These are post-PGR villages heavily dependent on social aid. And social aid is in the mayor’s hands. Also in the mayor’s hands are workplaces for kindergarten and elementary school teachers, as well as assistance for the unemployed.

K.A.

Above all there is no change. The present mayor used to be a director of the local PGR and people chose him. He is the mayor for the fifth time. People choose the same person because, as they say, “We know what we can expect.”

A.Z.

“Better the devil you know.” But I know that in the local election you had an opposition candidate.

J.A.

Yes, we convinced one good and courageous man to run for mayor. I phoned PIS (Law and Justice Party). I told them that the next day I would bring a guy and “could he become part of their list of candidates?” The next day, I drove around our candidate who announced he was running for mayor of Swiatki, and he lost by only 100 votes. We didn’t win but the opposition was initiated. The mayor was used to doing what he wanted, members of the parish council just signed the papers. I remember when it occurred that he wanted to sell the gravel excavation in Gologora without people’s knowledge and agreement. In Gologora, an illegal gravel excavation was underway. The mayor decided to sell this land in order to legalize extraction of the gravel. He put it to tender without people’s knowledge. When people realized that there would be 40-tonne trucks driving their country lanes, they rebelled. They collected signatures, and as an ally, I added the endorsement of the Let’s Love Warmia association, and the mayor cancelled the results of the tender.

A.Z.

So it looks like a lot has been done. But nonetheless I get the impression that you are a bit bitter.

J.A.

For years we have struggled with the same issues. You could really make something happen here. For example, in “culture houses.” Or fill in the old lakes with water. This terrain could become a great agro tourism region. And income from agro tourism is not small. This could enliven the people.

A.Z.

Jacek, you wanted to draw a new trail around the three nearby lakes.

J.A.

Now I know that you could fill in the old lakes and that we could have a trail around five lakes. In Legno, they have started to fill in the lakes. Only, all initiatives have to go through the system which rules here. And if an idea catches on, the ‘initiator’ is suddenly someone else and this person takes the prize, which is electoral success.

For example, the mayor of Dobre Miasto said, “I will agree to help with filling in the old lakes under the condition that the people whose land will be taken won’t complain.” This is appalling! People should get some compensation for their land. Now people are starting to withdraw from the project. Soon, the whole plan will fall apart.

A.Z.

Is it more profitable to pay people for their land because profits from tourism will compensate it?

J.A.

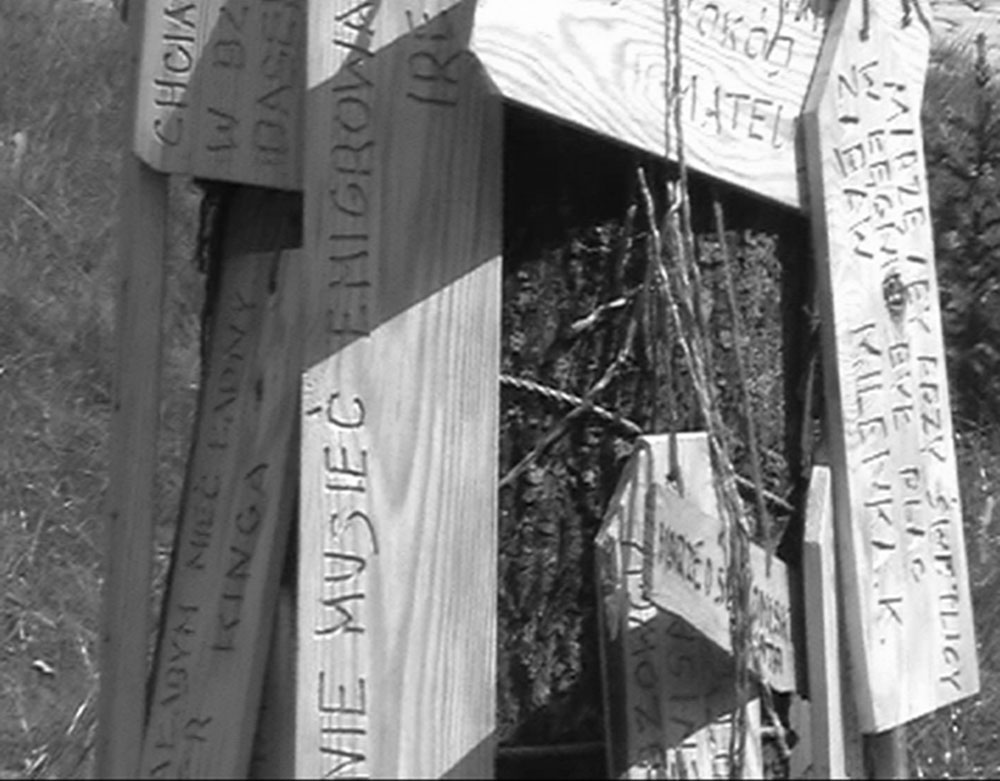

Yes. In Kwiecewo and Legno there are old, nowadays dry lakes. After filling, there could be a 500-hectare lake. In exchange for lost land, farmers could get money or land in other places. Tourists would come. The price of land around the lakes would grow. And we would keep some water in the “step-wind” Poland. I had a few good initiatives, such as the ‘tree of wishes.’ It concerned children from the villages. I drove to after-school clubs and asked children to write their wishes on a wooden plaque. Later, I deepened the writing with a router. These were the simplest wishes: that dad would stop drinking, that you could walk to school on a sidewalk, that the bus stop would have a cover.

K.A.

The child who wished that his dad would stop drinking signed with his name with the faith that something would change, that somebody would listen.

J.A.

And the mayor of Dobre Miasto declared that when the children hung their plaques, he would grant their wishes. Some of them he could actually make come true, but it was about integration as well. Children would know that there was a tree of wishes in Dobre Miasto and that some of those wishes come true.

K.A.

With the Plaques hung on the tree, the elections came around, the mayor did not have time, and after the elections completely forgot about their realization. Or, for another such example: for few months we were organizing a course in stained glass window making.

J.A.

There were tiny children enrolled but also big guys with tattoos. I wasn’t sure. I thought, “What is going to happen?” But slowly, they started to do something. At the beginning, people kept their distance and made stupid jokes. But suddenly, it caught on. People saw that connecting a few colored pieces of glass is quite a normal craft.

K.A.

Sometimes kids came with their mothers. They sat together and made stained glass windows. These were good times.

J.A.

Kate started to do origami with kids. Before Christmas, crowds of people came.

K.A.

We could see how strong the need for a community among the children was. It was very important for them that someone came to them, that someone was interested in them. And there was this surprise that they could do something. They take a stained-glass piece home and their parents ask, “Did you do that yourself?” And suddenly everybody starts to notice stained glass windows in church although they never paid any attention before. Children were emotional: “Wow, I’m making a stained window like there is in church”.

A.Z.

Were these classes free?

J.A.

Yes. I was supposed to be employed as a culture instructor and offering art classes in the culture-house and in after-school clubs. We were asked to give our terms. We gave them and that is how the case ended.

A.Z.

What conditions did you give?

J.A.

A 2500 ZL monthly salary for running art classes, plus the cost of commuting. To some villages, it is over 30 kilometers. It is especially difficult in winter.

A.Z.

Why did it end?

J.A.

Apparently there was no money. Some of the after-school clubs were closed, others were made smaller. The closest one in Legno isn’t open anymore.

K.A.

Jobs were liquidated because carers hadn’t finished secondary school. These were women from the villages, committed to their work.

J.A.

Officials came up with the idea that the carers had to have certain teaching qualifications. Where in these villages will you find people with such qualifications? A 600 ZL monthly salary for these women saved their families. And the authorities who earn several thousand a month say that they can’t find any other way to help those people. They walk passively past the places where unhappiness exists. We told the carers that they wouldn’t be dismissed, that we had been to a meeting with the voivod. Children had given her stained glass windows, which she had accepted. She had said that this was a superb initiative, that other parishes should follow the example. And look.

A.Z.

We still have to talk about the gravel excavation.

J.A.

This was two years after we moved in. I had already been involved with social activism. People knew about us. A man visited us and told us about the illegal gravel excavation. He said that the mayor was selling the gravel. This man himself wanted to take some gravel, but they told him to go away. And then he drove me to the excavation site and he showed me the place. Later on, it turned out that the parish can’t behave like a company and can’t get the rights for the gravel excavation. In addition, the excavation was taking place on the nature reserve.

A.Z.

Where is it?

J.A.

Eight kilometers away, at the Pasleka River reserve. You can’t even cut grass there. The gravel excavation is about 1.5 hectares large; gravel is extracted up to 9 meters. They extricated a few thousand cubic meters of it.

K.A.

In addition, this part of the Pasleka is a land reserve, and since 2004 has been protected by EU law as well.

J.A.

We wanted to show the hypocrisy of the authorities.

A.Z.

That the protection of the reserve stops when someone can make money on it?

J.A.

Yes, gravel excavated for private roads.

A.Z.

Who buys gravel there? Local people?

K.A.

Those who know how to make a deal with the mayor. A few years ago, he bought a house. Gravel used for the driveway up to his house was brought from the excavation site.

A.Z.

What did you do about it?

J.A.

I wrote a letter to the mayor with a request to explain the rules for excavation activity on the site of a nature reserve. I didn’t receive any answer, so I accused him of illegal activity. The case was dropped.

K.A.

When journalists came to the gravel excavation site, they found excavation equipment there. There was an article in the press with a picture of the machines.

A.Z.

And what about the court?

J.A.

They said that the mayor acted in good faith because the gravel was used for the parish’s needs, for example hardening the roads. But we submitted documents showing that the gravel was sold to private entities.

K.A.

The mayor defended himself saying that he didn’t sell the gravel but just used it to thank people for various services. Our mayor paid the mayor of Jankowo parish, a former prosecutor, with gravel from the illegal excavation in exchange for water.

J.A.

Then I decided I had to do something spectacular: a hunger strike, and towels and soap in the voivod’s office, the Clean Hands action. The prosecution office connected two cases: the pollution of the nature reserve by the overloaded water treatment plant and the gravel excavation against which they refused to take legal proceedings any further. The pollution of the nature reserve was treated as a “low social harm” and the mayor running the illegal gravel excavation had acted in good faith.

K.A.

And had carried out his duty, meaning maintaining the roads. In February 2003, the voivod’s geologist came, looked at the gravel excavation, and concluded that there was no sign of extraction. Nothing strange, it was February, and the snow was waist-high.

J.A.

Then, the mayor applied to the voivod for a concession to excavate gravel, but he didn’t get it. The mayor and the prosecutor’s office think like that: if the parish can’t get a concession to excavate because it’s not legally possible, they will do it without a concession and everything’s fine.

K.A.

We went to Rospuda, to Mr. Wajrak, when there were protests by ecologists.

J.A.

We spoke to them but only the Association for All Creatures was interested. They promised to monitor everything that happened with this case. We phoned Greenpeace, saying that there had been a breach of the laws regarding the Pasleka River nature reserve, and we thought that they would help us in the same way they now fight for the Rospuda Valley, and the aims are very similar. But in reply Greenpeace said that we could join in the work of saving whales.

A.Z.

Talk now about sitting in front of the voivod’s office in Olsztyn.

J.A.

I am concerned about state of the country. Using the law must be above all logical. Laws regarding nature conservation in my area were not being observed. That is why I demanded an improvement of the situation. I acted according to the law, but my activities didn’t have any effect. So, I decided to do something more spectacular. It was the same idea with the towels and soap.

A.Z.

What makes you so angry about this country?

J.A.

Administration is not used to solving people’s problems but to providing a service. Offices are privatized and then are grabbed by another authority. The central idea is economics and this is wrong because all qualities disappear, everything has a price. If you create this kind of social model then the society dies. All connections corrode. Everything is for sale.

A.Z.

Is that why you put on an orange overall and a cotton sack over your head in front of the marshal’s office in Olsztyn?

J.A.

Yes. I had my ID with my identification number on my neck. I had come to the conclusion that in the present social model, I am in a “state of possession”, a number. Just like in a camp. You get just enough to keep you productive.

A.Z.

A similar happening took place in a gigantic building of a chicken farm. People wore sacks with numbers on their heads.

J.A.

That was in 2006, 15 years after the beginning of the “martial law” (started on December 13, 1981). I wanted to show what had happened to our ideas and their destruction during the period of ‘martial law’. There was a printing press at my place, and among other papers, I published an oppositional weekly called “Los” (Fate). Sometimes, 3,000 copies of it lay under blankets. Printers came, we had some vodka and I was afraid, but I thought that opposition was a must.

A.Z.

Where was it?

J.A.

In my old flat on Lubelska Street, next to the Warsaw East railway station. It was social then, a common aim, and today there is no connection. And that is why you can call the happening at the chicken farm 20 years and one day after because it took place on December 14, 2006. We have been changed into a mass. We used to be a working class of cities and villages, now we are fertilizer for industry and banks. Some time ago, I would have shouted it out and would most probably have been beaten with truncheons by the police. Nowadays, I send my ID back to the ombudsman, saying that the state of the country hurts my civic feelings and that I don’t want to be a citizen any longer. But they just send the ID card back. They ignore you. People are blinded by the shops with a lot of products in them. But life is poor if it is only the fulfilment of material needs.

A.Z.

You use two different methods of intervention into, let’s call it, the local field of power. One is the execution of your right to criticize the way the authorities use their power, through protest, accusations, performance. You constantly check on the authorities and constantly monitor, importune them. You can call it being socially active. But one of your actions, bringing your own candidate to run in an election is different from social activism. Once you get involved in grooming local leaders, in deciding who will rule, do you cross this “thin, red line” and become a local politician yourself?

J.A.

If my actions don’t produce results, I look for alternatives.

A.Z.

Your artistic activity has become a form of civic protest, disobedience. Can it become a strictly political activity? You are a local leader, you initiate protests, you activate people.

K.A.

We are always open when it comes to action.

J.A.

We just react. Every action which takes place in the social field is politics. What we’ve done so far is protest. We want the law to be a tool for controlling authorities. But you are right: by getting involved in deciding who will govern we get involved in deciding what the reality around us will look like. There was a chance, we used it. There was the hope that something would change in the parish.

A.Z.

Politics is a sphere of conflict, a place where social needs are articulated, and where you demand that the conditions for their fulfilment be created. Are you still an artist or already a politician? You have mixed the languages.

J.A.

Being an artist is a state of the spirit. It is a creative activity, doesn’t matter in which field physics, art, or politics. You just use different instruments. Art can be both a way of seeking illumination as well as social interaction. Art, in a great way, prepares you for public activity because you have to publicly defend very strange objects and some strange actions. Art is an active form of language. Society is a moving train filled with people and their relations. The artist is the one who tries to open the window, often losing his fingers or teeth while doing so.